KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In Latin America, reserve portfolios are expanding to include US agency debt, equities, and investment-grade corporate bonds, primarily through ETFs.

- In the Middle East, global aggregate strategies remain the dominant approach for central banks seeking credit exposure, balancing the pursuit of incremental returns with traditional liquidity priorities.

- Asian central banks lead the world in reserve management sophistication, using advanced liquidity operations and derivatives to protect headline reserves while maintaining flexibility.

- The growth of Chinese RMB swap lines and modest RMB allocations across several regional central banks reflects deepening trade ties with China and cautious currency diversification, particularly in frontier markets.

- Rising fiscal and monetary pressures in DM economies, especially the US, are prompting EM central banks to reassess heavy concentration in US dollar assets.

- EM central banks now have an opportunity to exploit valuation dislocations in DM government debt while also exploring short-duration, low-volatility instruments that combine liquidity with income generation.

For much of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, emerging and frontier economies managed foreign exchange (FX) reserves with a narrow, almost singular focus: accumulate US dollars, invest in US Treasuries (USTs) and rely on these reserves as a last line of defense in times of crisis. Safety and liquidity were paramount; reserves were viewed as insurance policies rather than vehicles for investment or growth.

However, this practice has come under increasing pressure. A cascade of shocks—including regional and global financial crises, sharp swings in commodity prices, an extended period of ultra-low interest rates that reversed abruptly in 2022, the global pandemic, the war in Ukraine, a surging US dollar and the weaponization of sanctions—has pushed central banks to rethink their approach. The result has been a shift toward a more diversified and, in many cases, more sophisticated reserve management model, with growing willingness to expand eligible asset pools in pursuit of higher returns. Still, this evolution has been measured rather than radical. Recent drawdowns have reinforced the enduring priority of maintaining ample reserves in safe, liquid assets—often at the expense of higher returns—to ensure readiness for periods of stress.

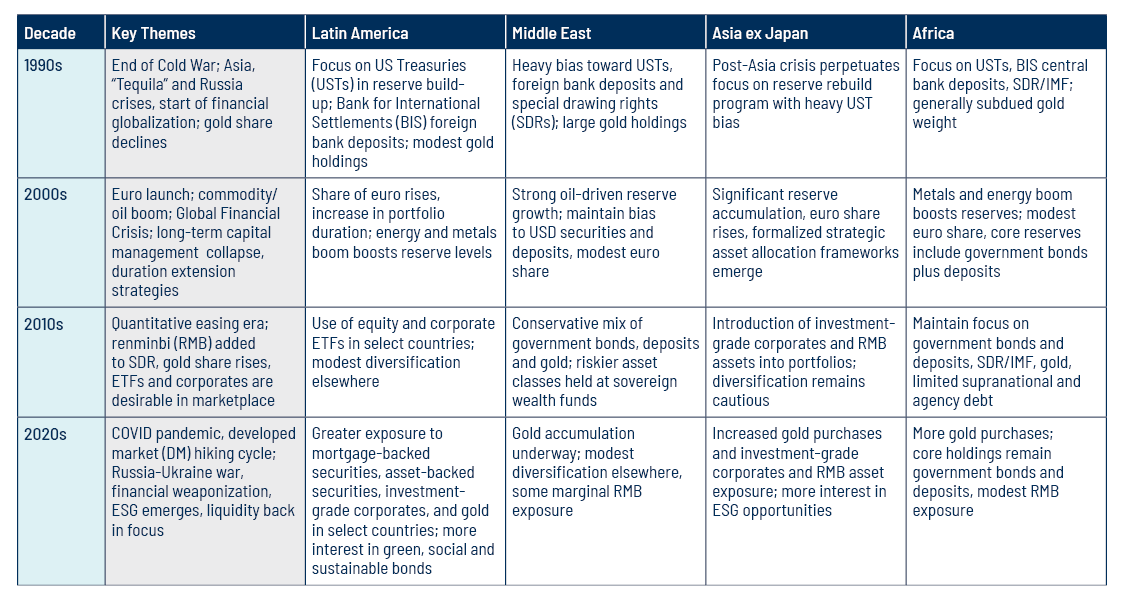

Exhibit 1 illustrates how emerging market (EM) central bank reserve portfolios have gradually diversified since the 1990s. During periods of strong reserve growth, managers bolstered their allocations to traditional assets such as gold, money market instruments and non-USD-denominated developed market (DM) government bonds as hedges against US policy uncertainty and its impact on the US dollar, inflation and interest rates. At the same time, they steadily expanded into non-traditional assets to generate additional income and returns, all within a more active and deliberate portfolio management framework.1

Latin America

In Latin America, reserve management has evolved in response to both internal reforms and external shocks. Historically, reserve managers in countries such as Brazil, Mexico and Peru maintained a highly conservative stance, shaped by decades of recurring financial and inflationary crises.2 This legacy fostered a strong preference for safety and liquidity with over 90% of reserves in US dollar assets, primarily government bonds and cash deposits and minimal gold holdings throughout the early 2010s.

Over the past decade, however, the region has experienced a marked shift. Political and economic reforms, more disciplined fiscal and monetary policies and a largely supportive global environment have buoyed macroeconomic fundamentals. With greater stability, central banks have become more adept at managing currency volatility, increasingly employing innovative derivative strategies and other risk management tools. They have also shifted focus from preserving capital to rebuilding reserves and pursuing higher-yielding opportunities.

Today, many central banks in the region have broadened the investment tranches of their reserve portfolios to include US agency debt, equities and investment-grade corporate bonds denominated in both US dollars and euros—primarily through ETFs.3 Others continue to prioritize sovereign, supranational and multilateral debt, though these portfolios are also evolving. Some reserve managers have prioritized sustainability by exploring green and social bonds issued by multilateral organizations—reflecting a broader shift toward integrating a sustainability focus into reserve management—while others are experimenting with climate-aware benchmarks for their corporate investments.

The Middle East

In the Middle East, reserve management is shaped by oil wealth, currency pegs and a distinct set of geopolitical dynamics. Over the years, central banks in the Gulf states have prioritized liquidity, placing Treasuries and dollar deposits at the core of their portfolios, while diversification into equities, private credit and other alternative assets has largely been the domain of sovereign wealth funds.

During the prolonged low-yield environment, some Gulf central banks cautiously ventured into investment-grade credit, seeking incremental returns and greater portfolio diversification. However, as interest rates have normalized and credit spreads tightened, the benefits of diversification have diminished and the appetite for credit has faded. More recently, US tariff policy has introduced a geopolitical risk premium to USD-denominated corporate bonds, further encouraging reserve managers to differentiate their portfolios based on divergent macroeconomic trajectories and interest rate paths, rather than increasing credit exposure.

At a broader level, there has been a notable shift away from global sovereign strategies toward global aggregate strategies as Gulf reserve managers have sought additional spread pickup. This trend has since slowed—and in some cases, reversed—as higher nominal yields have renewed the appeal of sovereign bonds. Nevertheless, global aggregate solutions remain the prevailing choice for central banks that continue to seek credit exposure.4

Gold has been at the center of the region’s more recent adjustments. Egypt has substantially increased its bullion reserves to rebuild market confidence while Qatar and the UAE have followed suit, signaling a regional pivot toward tangible security.5 In 2025, the UAE’s gold reserves alone rose by nearly 26%, reflecting both a deliberate move to diversify and a growing emphasis on building buffers against external shocks.6

Beyond gold, another notable development in the Middle East has been the rise of RMB liquidity lines, reflecting shifting trade patterns as much as diversification strategies. The UAE renewed its 35-billion swap line with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and deepened cooperation on payments and digital currencies. Saudi Arabia signed a three-year, 50-billion-facility agreement with the PBoC in late 2023.7 These facilities make RMB liquidity available when needed and have nudged some reserves teams to explore small RMB bond or deposit allocations. Globally, IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves data confirm the RMB’s gradual share gain from a very low base, suggesting cautious adoption rather than a wholesale shift.

Asia

Asia now sets the global standard for reserve management sophistication. With more than half the world’s reserves, the region’s central banks have pioneered institutional strategies that blend scale, agility and innovation. For example, South Korea, Singapore and India have developed advanced liquidity operations and derivatives programs, giving them flexibility that goes well beyond simple intervention.

Hong Kong’s Exchange Fund, which underpins its currency peg, invests across sovereigns, supranationals and quasi-government securities and also maintains an equity portfolio within its long-term allocation.8 China, meanwhile, has long been a major investor in US agency securities and continues to shift allocations between USTs and agencies in pursuit of yield and diversification.9

In addition to these strategies, Asian central banks actively manage duration, make extensive use of repo markets, employ bilateral swap lines tactically and use securities lending to mobilize liquidity without outright asset sales. During the Covid shock of 2020 and the sharp rise in the US dollar in 2022, these tools enabled Asian authorities to meet US dollar demand without materially depleting headline reserve levels.10 Amid concerns over US policy, gold buying has also accelerated in the region, with India and China leading the way, followed by Thailand and the Philippines.11

The RMB is now more entrenched in Asia than anywhere else, supported by a network of swap lines and channels for non-resident access to onshore bond markets. Central banks have taken pragmatic steps such as holding RMB deposits, establishing swap lines for contingency liquidity and testing RMB-denominated bonds. These measures are largely intended to match rising trade exposure to China while preserving crisis-time optionality. Although allocations remain small, the infrastructure for broader use has been strengthened.12

On the credit side, most Asian central banks (excluding Japan) remain generally conservative, focusing primarily on investment-grade-rated instruments. Some central banks do not allocate to corporate credit, while others allow credit exposure only within broader global fixed-income allocations rather than through dedicated mandates. Where credit allocations are permitted, external fund managers are often granted greater discretion to invest across sectors, particularly when a benchmark is in place. In contrast, internal reserve management teams tend to be more restrictive, often limiting exposure to specific sectors or to a list of pre-approved, high-quality issuers. Overall, the trend is toward increased participation in credit markets, but progress remains gradual and is shaped by each institution’s risk appetite and available resources.

Frontier Markets

Frontier economies, particularly those with deep investment and trade links to China, are also adapting their reserve strategies. Ten years ago, central banks in parts of Africa and Asia concentrated reserves in short-term USTs, cash deposits with global banks and gold. Their overriding priorities were liquidity and safety, reflecting both the small size of their reserves and their vulnerability to external shocks.

While prudence still dominates today, there are signs of change. Gold purchases by Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania have risen materially over the past few years, and there is a growing willingness among reserve managers to diversify further.13 For example, frontier central banks from Kenya, South Africa, Kazakhstan, Bangladesh and Cambodia, among others, have incorporated the RMB into their strategies.

Over the past decade, China has signed bilateral swap lines with many of its frontier neighbors such as Mongolia, Pakistan and Laos. These initially dormant swap lines were activated during balance-of-payments stress episodes, embedding RMB liquidity into local reserve frameworks.14 Several frontier central banks now also hold small amounts of Chinese government bonds, either directly through China’s interbank bond market or indirectly via Hong Kong’s Bond Connect. These allocations, typically 1% to 5% of reserves, remain modest but symbolically important, reflecting recognition that as trade exposure to China deepens, the RMB must have a role in official reserves.

Fault Lines to Monitor

EM central banks face a future landscape defined by complexity and shifting risks. Chief among these, and still a source of market instability, is the ongoing tariff threat by the Trump administration. If stagflation pressures and trade fragmentation intensify, the global economy will become more vulnerable to shocks and price volatility, making reserve management even more challenging for EM central banks.

While the US dollar remains unrivaled as the world’s safe and liquid reserve currency, central banks are increasingly questioning the wisdom of such heavy concentration in US dollar assets. Concerns over de-dollarization, coupled with the use of sanctions and asset freezes as tools of financial weaponization (e.g., Russia’s reserves in 2022) have sharpened these debates. They have also raised doubts about the reliability of emergency swap lines from major central banks such as the Federal Reserve (Fed) and European Central Bank in times of crisis.

Fiscal dominance is one risk that bears closer scrutiny. Historically, this has been associated with EM countries—Argentina, Brazil, Nigeria, Russia and Turkey—where excessive government borrowing, often financed by central bank money creation, triggered high inflation or hyperinflation, currency devaluations, loss of central bank credibility, and, in some cases, economic and social collapse. These episodes underscore the critical importance of central bank independence and fiscal discipline.

However, today, the risk is no longer confined to EM economies. In the US, rising deficits and debt servicing costs, combined with explicit political pressure on the Fed from the Trump administration to lower rates, have raised alarms that the country could be drifting toward a similar dynamic. Unlike distressed EM countries, however, the US benefits from issuing debt in its own currency and from strong global demand for dollars, which provides a significant buffer against sudden crises.

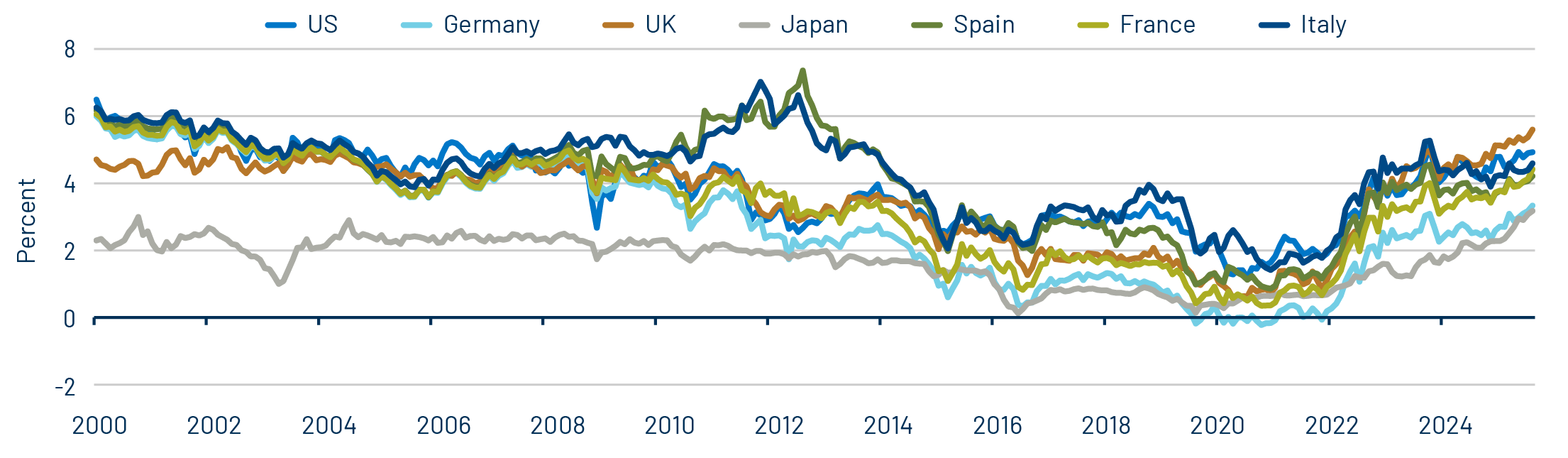

Yet, as the 2022 UK gilt market crisis shows, even advanced economies can be destabilized when fiscal and monetary credibility erode. External debt exposures add another layer: just as central banks in other countries that hold foreign-currency debt face pressures to stabilize exchange rates through interest-rate adjustments, the US could encounter analogous pressures if foreign investor confidence in USTs wanes. Any loss of confidence in the US could result in a negative feedback loop that forces a major repricing across all government bond yield curves and risk assets.

Time to Rethink Reserve Allocations

As global financial markets have expanded in breadth and sophistication, reserve management practices have likewise evolved to capture enhanced opportunities for return and diversification. Progress has, however, been uneven. The reasons are clear: economies are heterogeneous, with varying levels of complexity in their integration into global trade and finance. Consequently, reserve management strategies differ widely by region, country, and sometimes even within countries, depending on macroeconomic conditions, institutional capacity and risk tolerance. In some cases, political interference influences reserve decisions and outcomes. In others, reserve management has closely aligned with fiscal policy to support broader government objectives. The unifying principle across all approaches, however, remains the same: the imperative to safeguard economies against external shocks.

Over the past several decades, EM reserve managers have repeatedly confronted market volatility and policy uncertainty with varying degrees of success. Many have come to recognize, often reluctantly, that effective legacy strategies may no longer be adequate in today’s environment. For others, charting a sustainable path forward remains a formidable challenge necessitating rigorous analysis, reflection, conviction and consensus among internal stakeholders to recalibrate or reverse course.

In our perspective, central banks forging the greatest progress typically share one critical attribute: flexibility. They can adapt to evolving market conditions, reassess and adjust course when circumstances demand.

This adaptability is evident today. Several EM central banks are bolstering reserve portfolios by increasing allocations to gold and shortening the duration of their fixed-income holdings. While such actions might suggest a reversion to conservative postures of the past, in practice they reflect a more agile approach—one that involves consistently reassessing investment theses and adjusting course to mitigate emerging vulnerabilities.

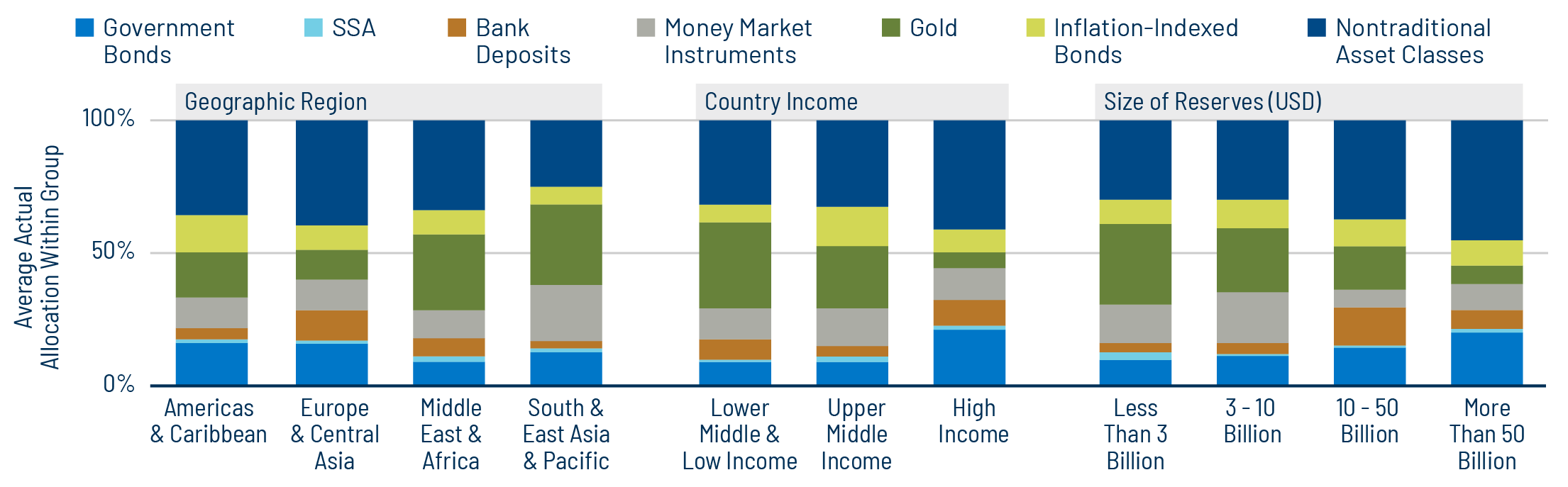

In this context, any new solutions that complement reserve management strategies must uphold the core objective of resilience. Excessive caution, however, should not impede measured experimentation and innovation. For central banks in lower- and middle-income economies with reserves typically between $3 billion and $10 billion, the foremost priority is to maintain reliable liquidity. At the same time, these institutions should consider opportunities that combine liquidity with income generation through low-volatility, short-duration assets.

For example, many smaller central banks, particularly in frontier markets, continue to rely heavily on bank deposits. Yet, money market funds (MMFs) offer a compelling alternative or complement and generally deliver higher returns and broader diversification. Empirical evidence demonstrates that MMF yields in the US typically remain elevated for longer periods than overnight bank deposit rates, owing to active duration management by MMF administrators within money market curves.15 Moreover, deposits often represent an inefficient use of bank balance sheet capacity, particularly as institutions face Basel III capital constraints and seek to optimize net interest margins. As policy rates decline, banks’ willingness to absorb deposits diminishes, reinforcing the attractiveness of MMFs as a source of both liquidity and resilience.16

By comparison, central banks in upper-middle- and higher-income economies, with reserve buffers generally exceeding $30 billion, have far greater investment and risk management flexibility. The recent surge in long-dated bond yields to multi-year highs presents a fresh opportunity to capitalize on valuation dislocations across DM government debt—an opportunity that was largely unavailable just a few years ago. Unlike past episodes, the current selloff is not limited to the US; yields across the European and Asia-Pacific regions have also returned to levels last seen in the early stages of the post-Covid tightening cycle. Historically, such periods of volatility have drawn in price-sensitive institutional investors, and larger EM central banks are now well positioned to act alongside them.

Seizing these opportunities will require active portfolio management. This entails closely monitoring economic, financial and political risks (both domestic and geopolitical), managing duration with discipline, dynamically rotating across asset classes and tactically using derivatives. These measures are particularly important in a context where US policy remains a dominant driver of volatility, DM government bonds and investment-grade credit can no longer be regarded as unquestioned safe havens and correlations across traditional reserve assets have become increasingly unstable.

Beyond traditional investments, larger EM central banks have the capacity to broaden their exposure in non-traditional asset classes, including securitized credit, covered bonds, EM debt, and emerging innovations such as central bank digital currencies.17 External asset managers can serve as valuable partners in these efforts, providing thought leadership, technology transfer and specialized training. At Western Asset, we have supported such initiatives by designing custom benchmarks, constructing models, integrating climate risk analysis into reserve strategies and conducting scenario-based stress testing to inform asset allocation decisions.

In Closing

A decade ago, the EM reserve manager archetype was a cautious custodian of Treasuries, focused almost exclusively on safety and liquidity. Today, these managers are active stewards: engineering liquidity, diversifying portfolios and confronting risks once considered the exclusive domain of developed economies.

Central bank reserves have moved beyond their traditional role as passive buffers against crises. They have become dynamic, strategically managed portfolios with the capacity to influence markets, liquidity and financial stability far beyond the institutions that hold them. In a world shaped by geopolitical shocks, financial volatility and fiscal strain in advanced economies, this evolution is not a minor adjustment but a structural transformation that could prove to be one of the most consequential financial developments of our time.

- Traditional asset classes include DM government bonds, bank deposits, money market instruments, supranational securities and gold. Non-traditional asset classes include investment-grade corporate bonds, DM equities, EM bonds, covered bonds, mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities, inflation-indexed bonds and central bank digital currencies.

- BIS, “Central banking in the Americas: Lessons from two decades,” November 2023

- Central banks commonly divide their reserve portfolios into tranches, including working capital, liquidity and investment, with the investment tranche usually representing the largest share. The allocation to each tranche, which has its own currency allocation, benchmark and risk parameters, is guided by reserve adequacy metrics (e.g., import coverage and the ratio of short-term debt to reserves). In countries that have limited reserves and greater short-term liquidity requirements, central banks are more likely to prioritize capital preservation and liquidity over maximizing investment returns.

- Global sovereign mandates focus exclusively on global government bonds. Global aggregate mandates include government, corporate, agency and securitized debt.

- Central Bank of Egypt, Annual Report, 2024

- Times of India, June 2025, “UAE’s gold reserves surge nearly 26%”

- Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority, PBoC press release, 2023

- Hong Kong Exchange Fund, Annual Report, 2024

- Financial Times, “How China is quietly diversifying from US Treasuries,” May 2, 2025

- BIS, “FX Markets and FX Interventions: Insights from a Markets Committee Workshop,” March 2024

- Reserve Bank of India, Annual Report 2024; World Gold Council, 2025

- Federal Reserve, “Internationalization of the Chinese Renminbi: Progress and Outlook,” August 2024

- Reuters, “African central banks’ gold rush faces liquidity, price risks, Fitch unit says,” July 30, 2025; China Daily, “African central banks turn to gold for stability,” August 6, 2025

- Boston University, “The Lender of First Resort?” April 2025

- MMFs continue to capture higher coupons on certificates of deposit, commercial paper, Treasury bills and repurchase agreements purchased before a rate cut. Because these funds typically have longer weighted-average maturities, their yields do not reprice immediately after a cut—a feature that makes them especially attractive to institutional investors.

- Under Basel III, institutional deposits not linked to day-to-day operations are deemed “non-operational” and subject to high outflow assumptions, making them costly for banks to hold and less attractive to retain.

- A central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a digital version of a nation’s fiat money, issued and backed by its central bank. In EM economies, CBDCs are viewed as tools to boost financial inclusion, modernize payments and reduce dependence on unstable local currencies.