Fiscal dominance occurs when large and persistent government deficits and debt dictate monetary policy, rather than the other way around. In such an environment, central banks may be pressured to keep interest rates low to facilitate government financing, even at the expense of their primary mandate to control inflation and support employment.

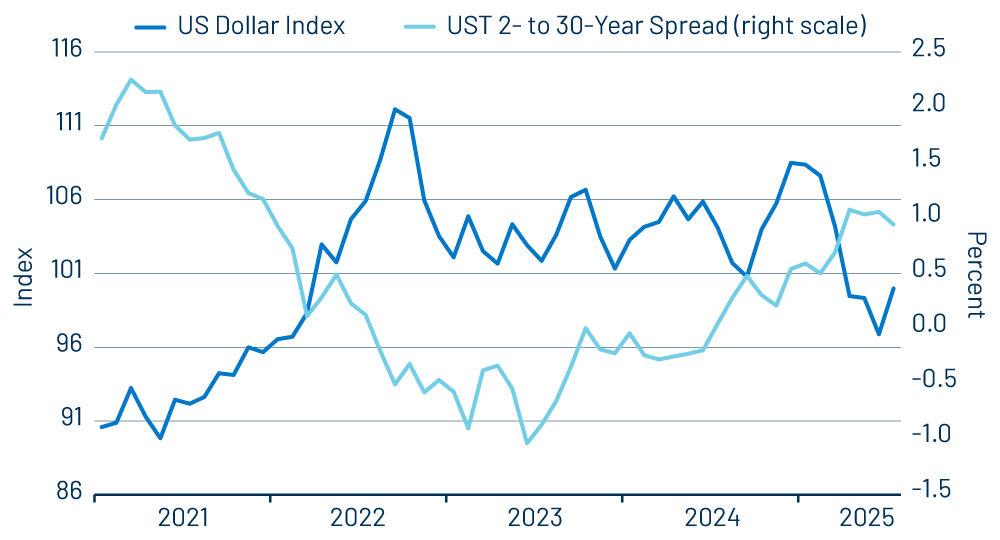

President Trump’s escalating demands for the Federal Reserve (Fed) to cut interest rates have thrust the issue of fiscal dominance in the US from theory into the headlines. Markets are already flashing warning signs—elevated long-term US Treasury (UST) yields, a weaker dollar and mounting investor unease—amid swelling deficits, a doubling of net interest expense over the past five years and a debt-to-GDP ratio above 120%.1 While Fed Chair Jerome Powell has publicly rejected the idea that debt servicing costs influence monetary policy decisions, the political pressure highlights growing fears that US fiscal needs could increasingly shape monetary policy and compromise central bank independence.

Empirical evidence from a global study of 52 countries over three decades shows that central banks often adjust interest rates in response to fiscal imbalances, especially in economies with limited central bank independence, high debt-to-GDP ratios or substantial foreign-currency-denominated debt.2 Depending on the debt composition, fiscal dominance pressures can push central banks to lower rates to ease domestic debt burdens or raise rates to stabilize the currency. Notably, these pressures have intensified since 2022, raising concerns that central banks could increasingly deviate from their primary goals in the coming years.3

Historically, fiscal dominance has been most closely associated with emerging market (EM) countries—Argentina, Brazil, Nigeria, Russia and Turkey—where excessive government borrowing, often financed by central bank money creation, triggered high inflation or hyperinflation, currency devaluations, loss of central bank credibility and, in some cases, economic and social collapse. These episodes underscore the critical importance of central bank independence and fiscal discipline.

However, today, the risk is no longer confined to EM economies. In the US, rising deficits and debt servicing costs, combined with explicit political pressure on the Fed from the Trump administration to lower rates, have raised alarms that the country could be drifting toward a similar dynamic. The recently enacted “One Big Beautiful Bill” illustrates this shift: initially projected to reduce deficits by $1.4 trillion over 10 years, it is now expected to add $3.4 trillion to the national debt over the same period.4

The implications for the UST market could be profound. Persistent deficits require the US Treasury to issue ever-larger quantities of debt, while investor willingness, both domestic and foreign, to absorb that supply at reasonable yields is not unlimited. If investors begin to doubt the Fed’s commitment to controlling inflation, or if fiscal policy is seen as unsustainable, they may demand higher yields, raising government borrowing costs and potentially creating a vicious cycle of rising deficits and debt service.

The 2022 UK gilt market crisis offers a cautionary example. Unfunded tax cuts in the government’s “mini-budget” triggered a surge in gilt yields, forcing leveraged pension funds to sell into a collapsing market and compelling the Bank of England to intervene by purchasing long-dated gilts. The episode led to rapid political fallout, including the resignation of Prime Minister Liz Truss after just 44 days, highlighting how quickly fiscal missteps can destabilize both markets and leadership.

The classic US example of fiscal dominance comes from World War II, when the Fed capped interest rates to facilitate war borrowing, contributing to a postwar inflation spike. The 1951 Treasury-Fed Accord restored central bank independence, creating safeguards that are once again being tested by today’s fiscal realities as rising deficits and political pressure threaten to pull monetary policy toward government financing needs.

Comparisons with past episodes highlight both similarities and differences. Like the WWII postwar period, the US now faces high debt and political pressure to suppress borrowing costs. Unlike distressed EM countries, however, the US benefits from issuing debt in its own currency and from strong global demand for dollars, providing a buffer against sudden crises. Yet, as the UK experience shows, even advanced economies can be destabilized when fiscal and monetary credibility erode. External debt exposures add another layer: just as central banks in other countries that hold foreign-currency debt face pressures to stabilize exchange rates through interest-rate adjustments, the US could encounter analogous pressures if foreign investor confidence in USTs wanes.

Looking ahead, we expect the US deficit to remain under pressure due to demographic trends, rising health care costs and compounding interest payments. While the Trump administration’s DOGE initiative aimed to rein in federal spending, verifiable savings have been limited. Without comprehensive reforms to entitlement programs and the tax system, deficits are likely to persist.

Despite these fiscal challenges, which are currently fueling investor unease, we believe that concerns about waning demand for USTs due to fiscal dominance may be overstated. The UST market benefits from a deep and diverse investor base, with foreign investors, domestic banks, insurance companies and pension funds well positioned to absorb future UST supply. So far this year, demand for USTs has remained resilient, supported by tight credit spreads in certain sectors, geopolitical uncertainty and elevated yields, which may cushion investors against rising rates and carry as well as total return potential should rates decline as we move into the final quarter of the year.

ENDNOTES

1. Financial Times, “Investors warn of ‘new era of fiscal dominance’ in global markets,” August 2025; Politico, “Trump’s Big Fiscal Dominance Play,” July 2025; US Treasury, “Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government,” July 2025

2. ScienceDirect, Kose et al., “Monetary Policy Under Fiscal Imbalances: Evidence from 52 Countries,” 2025

3. Ibid.

4. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, CBO projections, 2025