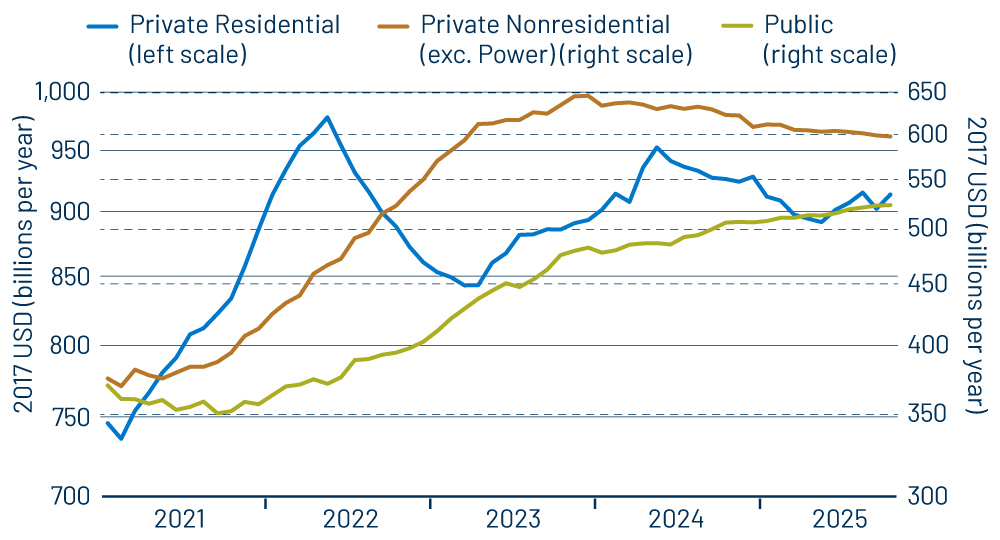

This morning the Census Bureau released the first construction spending data we have seen since late-September, prior to the government shutdown. These data suggest the same general decline in private-sector construction activity that has been in place for the last two years. Exhibit 1 shows data for both segments of private-sector construction as well as public construction. As always, there is some nuance to these trends.

For nonresidential activity, the decline since late-2023 was predominantly in construction of manufacturing capacity. Thanks to an array of federal government subsidies for manufacturing construction, activity there exploded from 2021 through 2023, rising from $75 billion per year in early-2021 to $240 billion per year by late-2023. That boom was bound to peak and subside, and that has happened in the last two years.

Interestingly enough, the subsidence has been relatively slight, and recent levels of manufacturing construction have been in the range of $210 billion per year. While that level is still dramatically higher than what we saw through 2020, it is still enough of a decline from the early-2024 peak to effect the slight downtrend in overall nonresidential activity that you see in Exhibit 1.

Residential construction is, of course, of special interest, and Exhibit 1 shows a slight downtrend in activity there as well. Within residential construction, remodeling activity has held steady. Multi-family (apartment) construction has declined modestly, but not as sharply as one might expect given the sharp increase in apartment construction that we saw coming out of the pandemic.

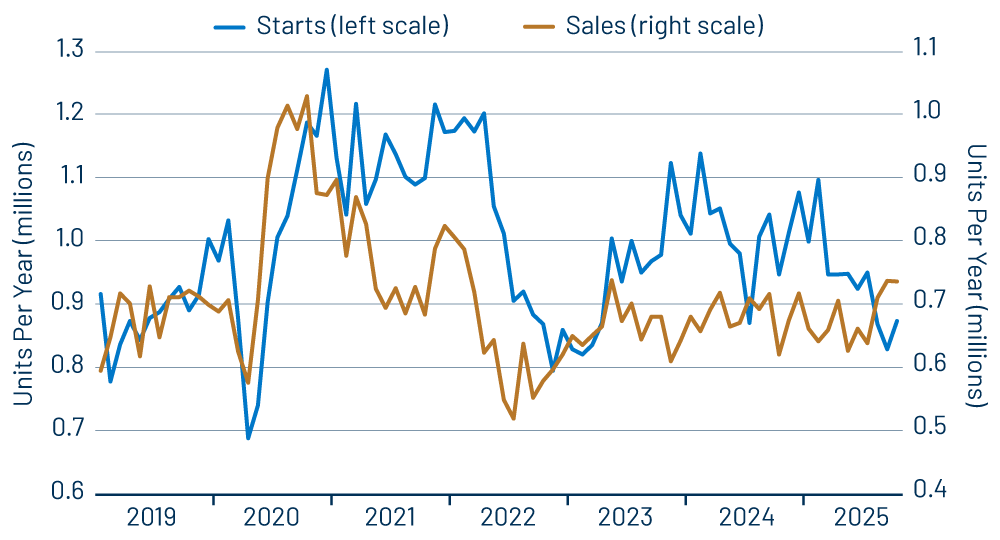

We saved single-family residential for last to focus on it more extensively, and Exhibit 2 shows further detail there by plotting single-family housing starts against single-family new-home sales. (Keep in mind that housing starts include owner-builds as well as new homes constructed for sale, and the scales in Exhibit 2 are staggered to allow for this.)

As suggested by the chart, builders were constructing homes faster than they could sell them over most of the last five years, and we think the 2025 downtrend in single-family starts is (finally!) a response to that overbuilding. As you can see, new-home sales have perked up a bit in recent months, and that may work to temper the decline in single-family activity.

All in all, the construction sector is exerting a modest drag on US economic activity. We mentioned in our last post that consumer spending and foreign trade data point to a robust 4Q GDP number. That robust growth will occur despite the negative drag from construction.

Moving forward, we would expect to see further declines in construction activity, but they are likely to remain modest, and they are also likely to be overwhelmed by decent growth in the rest of the US economy.