KEY TAKEAWAYS

- US mutual funds will be subject to a new SEC rule governing the use of derivatives and certain financing transactions.

- The new rule takes effect in August 2022, but will require time to implement.

- Many funds will need to develop a derivatives risk management program and designate someone to administer it.

- The new rule transitions from an obligations-based asset “coverage” approach to a Value at Risk (VaR)-based approach.

- VaR uses a model to estimate the magnitude and frequency of potential future losses.

- Funds will select the type of VaR limit that is appropriate for their strategy and instruments.

- Western Asset has already started assisting clients to help them prepare to satisfy the new Rule’s requirements.

Rule 18f-4 Changes for US Mutual Funds

On October 28, 2020, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted Rule 18f-4, which governs the use of derivatives and certain financing transactions by US mutual funds. The Rule emerges after almost a decade of gestation, and changes a framework that has been in place for decades.

The changes are a significant shift. Among other things, the Rule introduces “Value at Risk” (VaR) as a key component to limit fund derivative activity, replacing the prior asset coverage approach as the primary means of limiting leverage and mitigating derivatives risk. Compliance guidelines, governance and oversight stemming from the accompanying derivatives risk management programs will take time and effort to address. Mutual funds must comply by August 19, 2022.

Developing Derivatives Risk Management Programs

Fund managers and advisers will need to digest the requirements and nuances of the new Rule, develop and work through a project plan and coordinate with their respective boards. This will take a collaborative approach across disciplines. The lengthy implementation period established by the SEC recognizes the complexity and labor involved.

An officer of a fund or the fund’s adviser must be designated as a “derivatives risk manager” to administer a holistic derivatives risk management program at the fund level to address a variety of derivatives risks including market risk, liquidity risk, counterparty risk, operational risk and legal risk. Assigning someone with the requisite expertise and getting them involved in planning will be a priority.

Funds with only modest derivatives exposure (as measured by limits prescribed by the Rule and defined as “limited derivatives users”) will be required to adopt and implement policies to address derivatives risk, but will be exempted from the full requirements of the Rule. All other funds are subject to the full Rule requirements, including a full derivatives risk management program and VaR limits.

The Rule includes a new definition of derivative transactions. The new definition expressly prescribes that instruments a fund does not intend to settle physically or that take longer than 35 days to settle now qualify as derivatives. This will likely expand the scope of funds subject to the full Rule requirements beyond those funds that traditionally view themselves as active derivatives users.

In addition, funds that utilize reverse repurchase agreements and similar financing transactions also have the option to either meet traditional asset coverage requirements for all such transactions or may elect to treat such transactions as derivatives subject to the requirements of the Rule.

What Is Value at Risk?

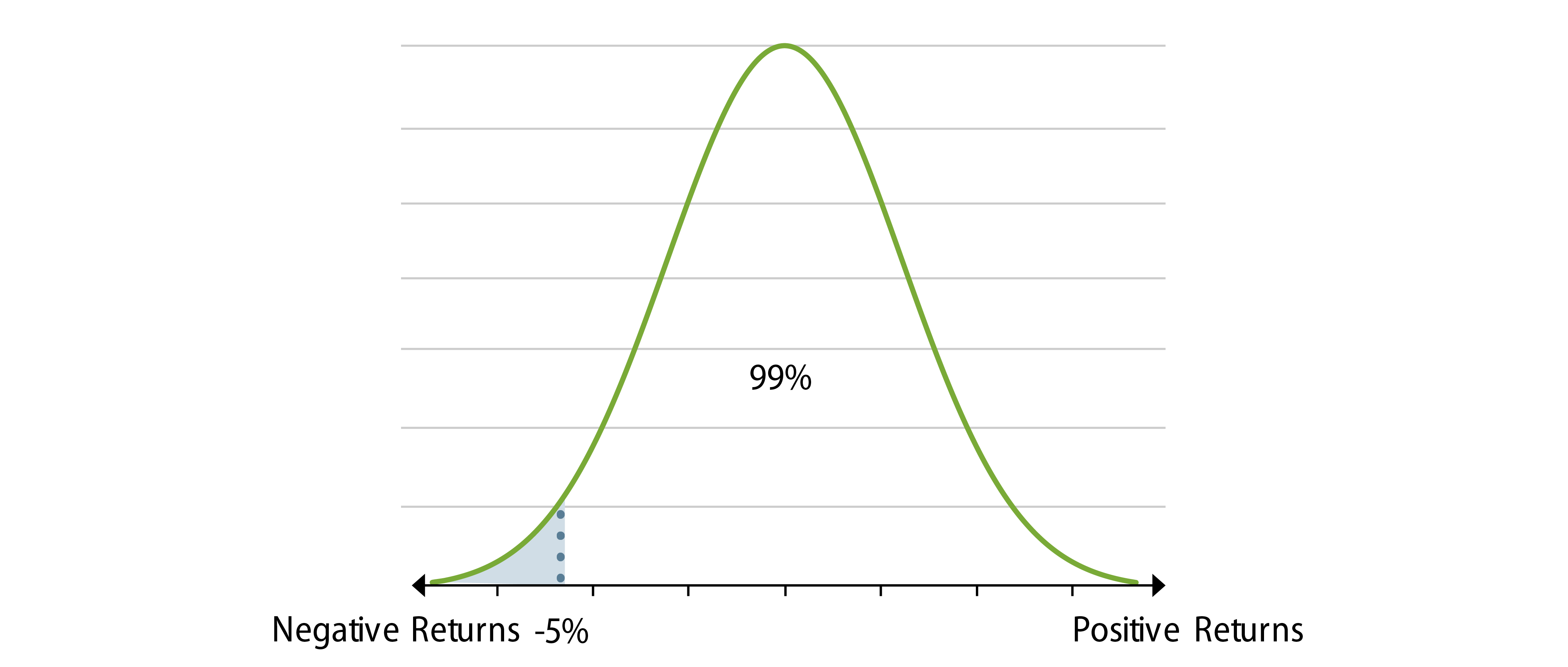

VaR uses statistical calculations to show a level of expected loss with a certain degree of confidence. For example, VaR might indicate that a fund has a 99% percent confidence level that losses will not exceed 5% in a month. The 5% number is the absolute VaR.

Relative VaR compares the absolute VaR of the portfolio or holding to a benchmark or reference portfolio. It is also expressed as a percentage, so a portfolio with a relative VaR of 200% has an absolute VaR twice as high as its point of comparison.

Thinking Ahead to Implementing Value at Risk Limits

Addressing VaR limits is the most complex aspect of the Rule. Ownership, design and validation of the VaR model and selection of the limits that will apply are key decision points. Whereas asset coverage methodologies and calculations have traditionally been the province of compliance professionals, the move to a VaR framework will incorporate risk professionals into the fund compliance program.

Each fund (other than any fund that is a limited derivatives user) will utilize a VaR model to monitor limits. The Rule also requires regular back-testing to ensure the VaR model reasonably reflects actual gains or losses. VaR models can emphasize different factors and estimate future behavior in different ways. Model design decisions can vary depending on fund holdings, often based on availability of historical information and the complexity of instruments. A fund can build and maintain its own model, rely on a sub-adviser or engage a third party as long as it meets the provisions of the Rule.

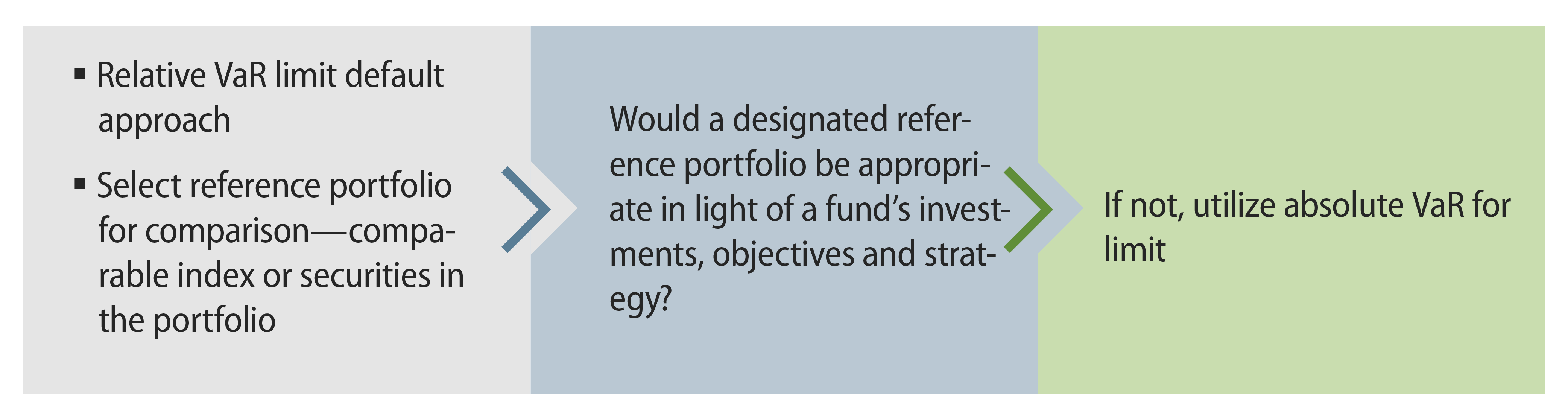

The Rule puts the burden on the fund to make decisions for which VaR approach is appropriate for a particular fund. The Rule generally requires that a fund use relative VaR, select an appropriate comparison benchmark or reference portfolio and be subject to a 200% limit for open-end funds. If relative VaR would not be appropriate in light of the fund’s strategy and instruments, a fund can opt to utilize absolute VaR. In that case, an open-end fund would be subject to a 20% absolute VaR limit.

Closed-end funds have a slightly different framework and need to plan accordingly. Closed-end funds with outstanding shares of a class of senior security that is a stock are subject to 250% relative VaR or 25% absolute VaR limits. The distinction for closed-end funds recognizes that the senior securities would raise a fund’s VaR even before taking into account any holdings or derivatives use.

Funds will need to analyze the relative and absolute VaR options, consider what is appropriate, and make a selection. While a fund can change its selection based upon a methodical assessment, these elections are not designed to be changeable on a day-to-day basis. There will be no ability to shift mid-day between options.

Funds will also need to plan for instances when a fund exceeds the VaR limits, including researching and validating overages and potential corrective action. Funds will need to keep in mind that outputs depend directly on the quality of inputs. Variations among models or exceptions produced by models may be explained by instrument set-ups rather than model designs or methodology.

Limited derivative user funds will also require an ongoing monitoring mechanism to confirm the fund remains below the applicable criteria of derivative use addresses overages by either remediating or implementing a full derivatives risk program and complying with all Rule 18f-4 provisions.

Western Asset’s Approach

Western Asset presently utilizes VaR in its risk management activities. It also manages commingled UCITS funds with VaR regulatory limits. Western Asset expects this experience to be helpful in working through Rule 18f-4 with its US mutual fund clients.

Rule 18f-4 applies at the fund level so it will not apply directly to Western Asset. Of course, in its role as sub-advisor, Western Asset will apply its normal portfolio management risk approach, but as a regulatory matter, it cannot build a derivatives risk management program to meet Rule 18f-4 specifications nor can it designate a derivatives risk manager under the Rule. A considerable open question is that of roles and responsibilities for VaR limit monitoring. Different mutual fund families might have different approaches and perspectives. Western Asset expects to have the capability to maintain a VaR model and monitor VaR limits. However, mutual fund clients may wish to maintain and administer their own VaR models. For example, mutual fund complexes with multiple funds and sub-advisers may desire consistency across all of their funds. Both approaches have trade-offs and implications for model design and administration, day-to-day monitoring and remediation (if and when needed). Western Asset expects to engage on these points with its mutual fund clients during their Rule 18f-4 implementation process. (For more information, please see the Appendix.)

An internal Western Asset working group is evaluating the Rule and its implications. Western Asset expects to work with its mutual fund clients to offer its perspectives through the process of selecting appropriate VaR approaches and reference portfolios where applicable. For example, Western Asset may be able to provide assessments of whether portfolios would qualify as limited derivatives users or how different VaR approaches might have operated in various market environments. In addition, Western Asset’s risk professionals have deep experience in operating VaR models, so the Firm may be able to help mutual fund clients to validate and assess their models.

Western Asset expects to conduct in-house monitoring, even if not for official Rule purposes. Funds intending to remain below the threshold for a limited derivatives user will be monitored (designation of instruments that qualify as derivative transactions is an aspect of that monitoring). Funds with VaR limits will be monitored based on their particular relative and absolute VaR elections. Those choosing relative VaR may have different reference portfolios, even for similar strategies.

Learning More

Additional commentary is available for readers interested in learning more:

- Looking Ahead—Observations and Open Questions

- VaR Basics

- Regulatory History of Coverage and the Path to Using VaR

- Rule 18f-4 VaR Limits and Limited Derivatives Users

- Western Asset’s Use of Derivatives

- Appendix—Value at Risk Model Ownership and Administration

Looking Ahead— Observations and Open Questions

Implementation of Rule 18f-4 will require funds to make a variety of decisions and changes. While Western Asset typically acts as a sub-adviser rather than an adviser or fund sponsor, the Firm expects to coordinate with its mutual fund clients to share observations, provide input, discuss logistics and otherwise assist clients in their efforts to comply by the August 2022 deadline.

Western Asset also believes that derivatives are a tool that works together with other available tools in the cause of effective portfolio management. Derivatives can help target particular risks and can be a more economical or efficient means by which to manage exposure. Derivatives themselves are not an isolated asset class or investment strategy. Western Asset maintains a variety of measures in different parts of the Firm that mitigate the risks targeted by Rule 18f-4, but they are not unified under a single derivatives risk program banner.

Roles and Responsibilities

Rule 18f-4 applies at the fund level so it will not apply directly to Western Asset. Western Asset maintains a variety of practices that address derivative risks contemplated by Rule 18f-4. However, the Firm’s practices are not specifically designed to address Rule 18f-4 compliance, and Western Asset is not planning to name a “derivatives risk manager.” By regulation, Western Asset cannot assume overall responsibility for constructing and maintaining a derivatives risk management program to reflect all Rule 18f-4 parameters. Western Asset will continue to tailor its risk infrastructure as prudent to perform its sub-adviser services and will need to continue to address regulatory and contractual expectations of clients who are not US mutual funds.

One example with specific application to Rule 18f-4 is stress-testing designed to evaluate potential losses to a fund’s portfolio under stressed conditions. Western Asset conducts stress-testing scenarios and analyses in the ordinary course of providing its services, but those stress tests may not be performed using official fund books and records or pursuant to Rule 18f-4 specifications or practice. They also will not fully take into account situations in which Western Asset is managing a sleeve in a multi-manager fund.

Similar to compliance with Rule 22e-4 addressing fund liquidity, mutual fund complexes with multiple funds and sub-advisers may be best positioned to design and administer a comprehensive program that addresses the logistics necessary to meet the fund-level regulatory requirements. In addition, mutual funds will take the lead for prospectus disclosures and regulatory filings required under Rule 18f-4.

There are implementation decisions to be made regarding roles and responsibilities for VaR limit monitoring. As Rule 18f-4 is a fund-level requirement, different mutual fund families might have different approaches and perspectives. Western Asset can assist fund clients in complying with Rule 18f-4 limits in one of two ways:

- A fund could adopt Western Asset’s VaR model, in which case Western Asset would apply that model and related limits to the fund; or

- A fund could use its own model and supply Western Asset with the output in a timely manner, in which case Western Asset would apply limits derived from that model to the portfolio.

Western Asset recognizes some clients may prefer to maintain their own VaR models and/or monitoring VaR via a third party vendor for different reasons. Western Asset can accommodate either approach (for more details, please see in the Appendix).

Both approaches come with their own implications. There may be advantages in having Western Asset take the lead in the role of subject matter knowledge expert of the portfolios and instruments and the ability to de-construct the model when approaching or exceeding limits to effectively determine next steps. Without such knowledge, taking remedial measures may be based on best guesses rather than hard data. However, mutual fund clients may wish to maintain and administer their own VaR models. For example, mutual fund complexes with multiple funds and sub-advisers may desire consistency across all funds to meet fund-level regulatory requirements. In these cases, there would be a separation between those monitoring and those making investment decisions that needs to be considered.

Funds may have their own official models and monitor VaR limits, but Western Asset will need to avoid exceeding limits in day-to-day trading. Whether that requires some form of parallel or shadow monitoring remains to be seen. A fund sponsor will likely need to deliver daily VaR calculations to Western Asset if the sponsor desires to have Western Asset directly enforce limits based on the fund’s model. Times of extreme market volatility may test these arrangements, so there will likely need to be advance discussion of VaR limit handling in those cases.

Both approaches have trade-offs and implications for model design and administration, day-to-day monitoring and remediation (if and when needed). If a mutual fund client prefers to retain ownership of the official VaR model for a fund, it may be prudent for the client and Western Asset to compare notes periodically to understand each other’s perspectives. As noted earlier, there may be nuances in security set-up that can impact model results separate and apart from the model methodology. There may also be design choices in the model itself. Full reconciliation between models may not be necessary or even possible, but some coordination may help mitigate risks inherent in attempting to validate results in times of market stress.

Fund complexes that are fully integrated with asset management services performed in-house will have less of a challenge with VaR limit monitoring than complexes that primarily utilize third party sub-advisers or fund complexes with a mix of in-house management and third-party sub-advisers. The challenges may be sharper for multi-manager funds with sub-advisers managing different sleeves of the same fund. Determining who will officially own responsibility for the daily maintenance and monitoring of VaR limits for Rule 18f-4 purposes will be a discussion point well before the August 2022 compliance date.

Regardless of which party takes the lead for which roles and duties in order to be in compliance with Rule 18f-4, documentation will be necessary in anticipation of potential future SEC examinations. Rule 18f-4 has many moving parts and requirements, so a fund will need to be able to demonstrate that it has correctly identified and appropriately addressed each element. Being able to explain model methodology and operation will also be necessary during an SEC examination.

Relative VaR Designated Reference Portfolio Selection and Absolute VaR Election

There will likely be a role for Western Asset to play in helping funds to select their designated reference portfolio under the relative VaR limits. Rule 18f-4 leaves the selection up to each individual fund within certain boundaries. The process will require identifying, evaluating and selecting among the various options. There may be funds for which the relative VaR approach is not appropriate and the fund may choose to adopt an absolute VaR standard.

In both cases, Western Asset may be able to offer perspective to help make and document the assessment and selection.

Limited Derivative Users

Funds falling under the limited derivative user exemption will require ongoing monitoring to ensure they remain below the limit. While fund clients may make their own official determinations and do their own official monitoring, these clients may appreciate proactive efforts that Western Asset can take to monitor its own trading activity to prevent exceeding those limits or evaluating whether a fund should cease operating as a limited derivative user.

That will require a methodology to manage underlying trade data. One area of potential complexity is determining how to systematically identify and account for instruments that meet delayed settlement criteria and can be excluded from the calculation (or even if it is feasible to consistently identify such instruments). For example, determining and documenting the “intent” of an investment professional to settle physically is not necessarily an objectively ascertainable data element. In addition, intent can change. Another area for further analysis is determining which interest-rate and currency derivatives meet the conditions for hedging and which do not, and if it is operationally feasible to distinguish between them.

Funds that have traditionally not viewed themselves as active derivative users might have a difficult time meeting the exemption for a limited derivatives user. Answering questions regarding the treatment of instruments like these under the Rule will be a task to be wrestled with more broadly. There may be different ways to address the issues and there may be changes in the way certain instruments trade. Given the challenges, there may also be further interpretative SEC guidance before the Rule takes effect.

Reverse Repurchase Agreements

Rule 18f-4 permits two different treatments for funds utilizing reverse repurchase agreements. One option is to consider all reverse repurchase transactions and similar financing transactions as derivative transactions and therefore subject to the same VaR limits applicable to other derivatives. The other option is to treat such transactions akin to borrowings and therefore subject to Section 18’s asset coverage requirements. Notably, a fund must be consistent in its approach, so it must treat different financing transactions in the same manner (such as reverse repurchase agreements and tender option bonds).

The treatment decision rests with the fund but coordination between sub-adviser and the fund will likely be required to make the election.

Experience With UCITS Funds That Utilize VaR Limits

Western Asset has prior experience with managing UCITS funds that have a similar approach to that which the SEC has adopted. There are nuances and differences, but there are also useful similarities. Importantly, the VaR philosophy and limits are similar. The Firm believes that this experience will aid in making the transition for its US mutual fund clients.

The Future for Accounts That Are Not US-Mutual Funds

Rule 18f-4 only applies to the use of derivatives or financing transactions in US mutual funds. The Firm has historically utilized asset coverage rules for its separate accounts and other unregistered vehicles. It remains to be seen whether shifting to follow a VaR approach is prudent or consistent with client preference for these portfolios.

VaR Basics

What Is Value at Risk or VaR?

VaR is a forward-looking estimate of maximum future loss. VaR indicates the magnitude of daily losses a fund can expect and how often different loss levels will occur. It requires a specified time frame and a confidence level.

It seeks to isolate market risk (as opposed to other types of risk such as liquidity risk, credit/counterparty risk, or operational risk).

The estimate is more than a simple calculation based on the holdings of the portfolio. VaR estimates potential movement in relevant markets and then applies that model to current holdings of the portfolio to estimate the probability of large losses.

VaR estimates are forecast estimates in the sense that they use the current holdings of the portfolio to calculate potential future results. However, the behavior of the factors in the model are typically estimated using backward-looking historical data. The simulated behavior of the factors is usually characterized by volatility and correlation, but tail behavior and expected change are also relevant to the calculation of VaR. Examples of factors include the change in interest rates, currency or credit spreads.

At a high level, VaR is used to try to avoid surprises regarding the frequency and magnitude of potential losses. VaR uses statistical calculations to show a level of expected loss with a certain degree of confidence. VaR calculations can be run on a single holding, but can also be run on a portfolio. The VaR for a portfolio looks at the potential return implications for the portfolio holdings taken together as a whole. For example, the VaR for a portfolio might be expressed by saying that we are 99% percent confident that our loss will not exceed 5% in a month. The 5% number is the portfolio’s absolute VaR. It is a stand-alone metric.

VaR acknowledges that there may be months with losses greater than 5%, but those are rare (one out of 100 months as estimated by the model with a 99% level of confidence). Those losses may be important to consider as a matter of risk management. Risk management tools other than VaR, such as stress-testing, are employed for these purposes.

Losses can be expressed in different descriptive measures, such as a currency (dollars or euros, for example) or percentage terms (commonly in basis points). A VaR metric can be expressed as a loss of $1000 or 5% or 500 basis points depending on the unit of measure the underlying data uses to describe returns.

What Drives VaR Calculations?

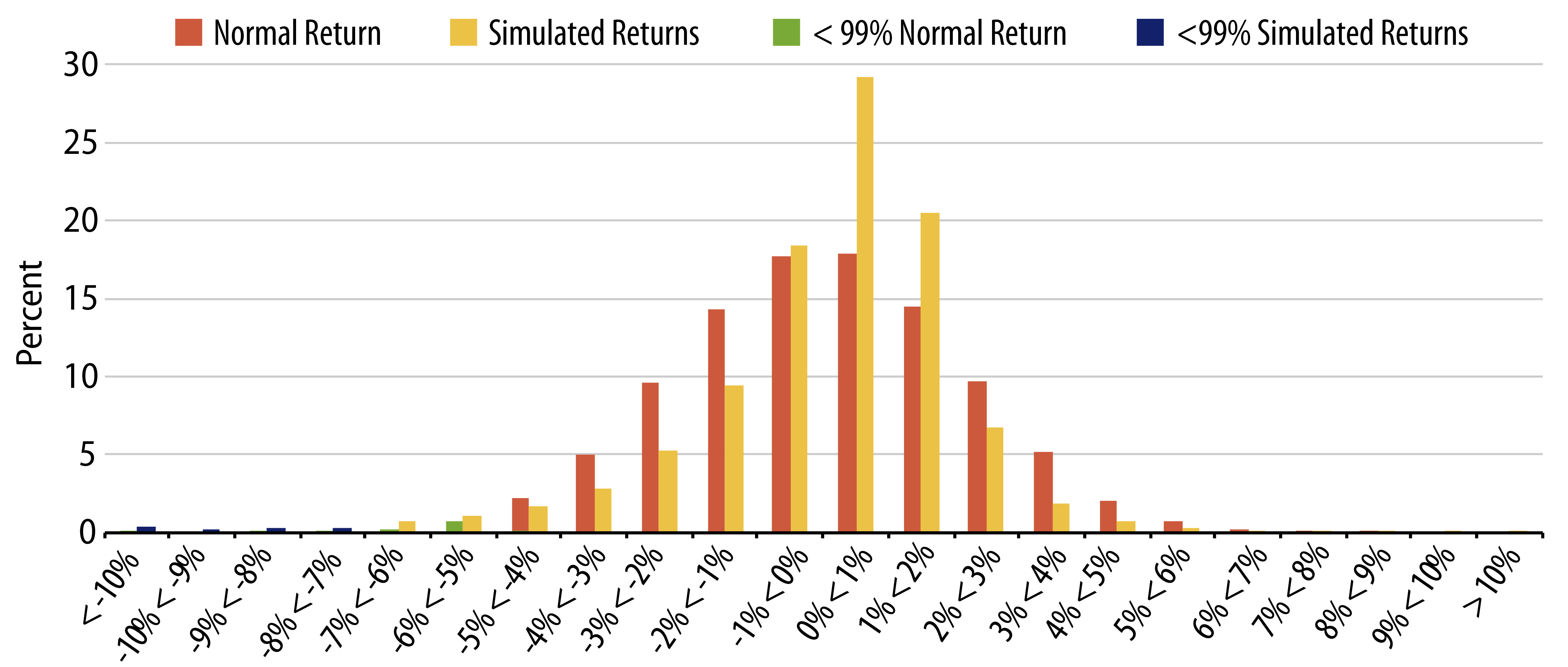

VaR depends on the process used to determine the population of returns. A VaR calculation is inherently a model because it seeks to estimate the possible returns of the current portfolio holdings. Back-testing continually evaluates current experience against the VaR model and helps to ensure the VaR model continues to reflect actual profits and losses in the real world. Too many variations between actual and expected experience would suggest the model requires further refinement and calibration. As much as VaR seeks to estimate the frequency of different future returns, a model that relies on return data from the past cannot perfectly predict return experience of current portfolios and markets.

VaR calculations rely on two key parameters: confidence level and time horizon for returns. Both are important to VaR in general and for Rule 18f-4, in particular.

A portfolio’s VaR (i.e., minimum expected loss for a given set of worst returns) is inherently linked to the confidence level. For the same set of data, a higher confidence level could result in a larger loss level because we are more confident that the loss will not exceed that higher number. Conversely, a lower confidence level could result in a lower VaR number because we are less confident that losses will not exceed that number.

Estimating the distribution of returns also depends on the time horizon and methodology used. Model inputs are typically actual historical market activity. The historical time horizon establishes the data set used to calculate correlations and volatilities. Also, different weighting methodologies can materially affect the results. The selection of time horizon and methodology is important because those inputs will be used to estimate forward behavior.

- A higher confidence level could result in greater losses

- A lower confidence level could result in a lower VaR

Estimating the distribution of returns also depends on the time horizon used

- Shorter time horizons may span volatile markets and add noise into a model

- Longer time horizons may reach back to markets that are not good baselines for current market conditions or potential future behavior

- VaR model time horizons typically range between three months and several years

A brief historical time period may prove insufficient to credibly produce estimates or the data may overemphasize a specific market environment. Short time horizons may undergo volatile markets and add noise into a model, which can encourage or force action based on a brief experience that may be unusual or unrepresentative. On the other hand, too long of a time period may reach back to markets that are not good baselines for current markets and potential future behavior. Historical time frames used to calculate volatilities and correlations for VaR models typically range between three months and several years.

Different market participants use different forward-looking time horizons for their VaR calculations depending on the sensitivity required. A bank, for example, may use a one-day time horizon to estimate potential loss in the next business day when evaluating its holdings because of daily capital requirements and extremely low risk tolerance. A commingled fund with longer-term investment horizons may not have the same level of sensitivity. Rule 18f-4, for example, requires a 20-day time horizon.

How Are VaR Calculation Methodologies Developed?

As a general proposition, building VaR calculations has three embedded layers. Decisions at each layer can influence the output. Different approaches may make sense for different portfolios or objectives.

Regardless of the approach, the starting point is understanding the instruments involved. While a fairly standard listed equity strategy might be less complicated, a broad-based fixed-income strategy can involve many different instruments with their own attributes and characteristics. The more variables and optionality that are built into an instrument, the more critical it is to understand the instruments in order to develop an effective VaR model. (Note that changes over time require ongoing diligence and vigilance to ensure the model remains sound based on accurate and up to date information.)

Once the instruments are understood, the next question is the selection of factors involved. The number and type of factors at the heart of VaR models often depends on the assets involved. A portfolio with only less complex assets might use a model with fewer factors. A portfolio with a wider variety of security types might use a model with more factors. The goal is to develop a model that effectively captures the risks in the portfolio and can generate credible forward estimates.

Factors such as interest-rate duration, currency exposures, and sector exposures are common candidates, but more complex models would incorporate more factors. Of course, the more complicated or esoteric factors that are involved, the more complex the underlying data becomes to gather, analyze and maintain—particularly as time passes, market conditions fluctuate and the underlying data organically shifts over time.

The next step is deciding how the model will handle the historical correlations and volatilities between and among the factors and the appropriate time horizon. The simplest approach is known as “delta-normal” and assumes linear relationships between the factors and portfolio return that behave in a reasonably expected manner over time (i.e., variance grows linearly over time). In linear relationships, factors are related to each other in a simple way where one factor is directly proportional to the other.

Volatilities and correlations are typically calculated from this historical data. When combined with the portfolio exposures, calculating VaR for any time horizon is a simple matrix calculation and a little bit of math using the delta-normal model. While such a model requires design decisions, if reasonable choices are made and the main exposures of a portfolio are captured, the VaR results will be relatively consistent with more complicated models for most portfolios.

However, a more sophisticated approach to VaR leaves behind the assumption that variables are related in a linear fashion. VaR is intended to be a “tail statistic” meaning it measures the likelihood of rare events (large losses) and a simple model may not be sufficient. Returns are often not a linear function of factors, and mathematical formulas (or pricing models) can attempt to better account for behavior that is not directly proportional. Graphed, the relationships generated by these formulas show curves or other patterns that are not proportional in all cases. For example, certain factor exposures change dramatically depending on their inputs or change to varying degrees over time. Financial returns can experience “fat tails” (large, but infrequent) or other peculiar properties. There can be idiosyncratic and default risk, which are typically treated with a separate factor model.

Again, the nature of the portfolio holdings may impact the choice of approach. A fixed-income portfolio comprised of mostly US Treasury bonds and some Treasury futures would likely be able to utilize a “delta-normal” approach. However, fixed-income portfolios with mortgage pools, options and callable bonds may require more nuanced or complex modeling. Those types of portfolios may require engineering to operate in a “delta-normal” model or they may suggest adjusting to a non-linear approach. Non-normal distributions and more refined correlations can add precision even though their application comes at the cost of simplicity.

With that base, the next decision is how to apply the data and correlations, and to generate actual VaR metrics. There are three common methodologies.

- Historical Approach

A historical approach takes observed returns from the past and uses them to estimate future behavior based on security returns and how they historically behaved. For a historical approach, the actual security returns effectively serve as factors. This approach effectively seeks to “re-live” history as if the current portfolio had existed previously. The historical approach is common for equity portfolios where there are long time-series of data sets available for the same instruments. In the world of VaR models, the historical approach is less taxing in terms of time and complexity because of the relatively direct path between historical experience and projecting future experience. Because a historical VaR approach is based on actual historical experience, it does not require assumptions about relationships between the security returns and factors. - Monte Carlo Approach

A Monte Carlo approach, however, takes the model estimates and runs them through a large number of simulations. The random “what if” scenarios produce a range of hypothetical results. Running a large number of simulations can take time to execute and organize the results. The Monte Carlo approach is often used for fixed-income portfolios because of the lack of stable historical data for each instrument. Bonds are issued and then are called or mature or are converted. Options expire. Mortgage instruments pre-pay and amortize. In theory, either a “delta-normal” or non-normal foundation can be used with a Monte Carlo VaR but the greater sophistication required typically incorporates a non-normal approach for added precision. - Parametric Approach

A third and less frequently used approach is parametric, which specifies parameters and seeks to predict future results. Like the historical approach, it typically starts with historical data, but uses history to identify and develop set parameters such as volatility and correlation. These parameters are assumed to forecast forward returns. Other causes for return behavior are assumed to be small enough to ignore (back-testing can validate this assumption). Compared to the other two approaches, parametric is typically viewed as simpler, faster and easier to analyze. Results are determined by an equation written in terms of parameters (i.e., parametric) and thus the relationship between the result and the inputs is easy to ascertain. A parametric approach typically is based on a linear delta-normal approach rather than a non-linear approach because the math is easier to build and solve.

Who Builds and Maintains the Model?

Experienced risk departments of asset managers with knowledgeable staff and technology resources will be able to build and maintain their own models. Some advisers already do this because they utilize VaR for their own risk management purposes or for handling UCITS funds with VaR thresholds. The simpler the model, the easier it is to build and maintain. More complex models require more effort and resources.

Any model requires ongoing maintenance. As time goes on, updated data spanning the selected time horizon must be gathered, relevant correlations calculated and new securities must be correctly modeled. Back-testing is also required to ensure the model remains a reasonable estimate of the real world.

Another option is to engage the services of third party vendors who can take the lead for maintaining the model. A third party vendor may be able to bring scale and helpful experience necessary to handle complex instruments. A client using a third party still must have an understanding of the factors used and other design parameters in order to understand the results.

Regardless of the model design or who builds or operates the models, ensuring an accurate understanding of the instruments themselves is foundational. Different model results can often be explained by resolving questions of instrument characteristics rather than the model or methodology itself.

Regulatory History

The Path to VaR for US Mutual Funds

Section 18 of the Investment Company Act of 1940 does not specifically regulate investments in derivatives. Instead, Section 18 limits the issuance of securities that are senior to equity as a form of indebtedness and potential source of leverage exposure. In April 1979, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) published Investment Company Act Release 10666 as a policy statement to provide guidance applying Section 18’s limitations on indebtedness to reverse repurchase agreements, firm commitment agreements, and standby commitment agreements. The principles in Release 10666 were thereafter interpreted broadly to encompass any evidence of indebtedness and extended to other types of derivative instruments.

SEC guidance permitted funds to have indebtedness arrangements such as these as long as fund obligations were “covered.” Put simply, a fund could “cover” those obligations with other assets to offset the leveraging effect the derivative instruments had created. The concept of “hard segregation” (designating and segregating assets for cover) evolved into the concept “soft segregation” (holding a sufficient amount of liquid instruments without designating certain assets). In either case, the intent was that the amount of “cover” available would limit a fund’s use of derivatives.

The regulatory analysis of derivatives use under this framework can be complex. How much cover is required for which instruments? What instruments qualify to be used as cover? Closed-end funds have their own mechanisms that permit outright borrowing, so how does that fit in?

The SEC decided to revise the rules for derivatives use by US mutual funds for two principal reasons. First, an updated and more comprehensive approach was necessary in light of the patchwork of decades of SEC regulatory guidance since publication of Release 10666. The SEC was concerned about inconsistent industry practices that had developed over time, particularly in light of the broad range of fund derivative use. A standardized regulatory framework could facilitate a level competitive landscape and improve the SEC’s ability to monitor compliance with regulatory expectations. Second, the SEC sought to address concerns that existing practices may not adequately protect fund investors from the risks of potentially significant losses around leverage and increased fund volatility that Section 18 was originally intended to address.

Leverage is the ability of a fund or investor to commit more capital than it has equity to invest. The difference between the two is borrowed in some form. The relationship between leverage and derivatives depends on how the derivatives are used. Derivatives can be used to gain exposure and hedge risk. They can also have the potential to create leverage and magnify gains and losses. A full discussion of the different types of derivatives, their potential uses, and their risks is beyond the scope of this overview, but Rule 18f-4 seeks to limit the use of derivatives by funds and put in place a governance and oversight structure to manage the risks.

Moving to a VaR Approach to Mitigate Leverage Risk

Rule 18f-4 continues the SEC’s policy objectives regarding leverage limits arising from derivatives, but shifts from an asset coverage approach to VaR as the primary mechanism to achieve those limits. These are separate concepts and the shift will require changes. VaR has become a common means of risk management and VaR thresholds are already used in some other regulatory frameworks to limit derivatives risk. The VaR approach is designed to use modern risk management analysis and techniques to provide a more universal set of practices across all mutual funds using derivatives to any significant degree.

The SEC acknowledges that VaR is not itself a leverage measure. The SEC believes that a VaR limit can be a useful tool—when combined with other risk management tools—to mitigate the risk that a fund has to the risk of losses due to the possible leveraging effect of derivatives.

Derivatives may or may not add market risk (such as in the case of a currency forward which might be a hedge of an existing position or a naked currency position). In practice, it can be difficult to distinguish between derivatives that take additional risk and those that mitigate risk. The SEC believes that derivative use in general presents risk and should be constrained.

The concept of coverage, however, has not been abandoned completely. Funds that are designed to be levered and do so by means such as bank borrowing or issuing bonds for additional financing must still comply with the 300% asset coverage limitations established in Section 18 with respect to those borrowings. Closed-end funds are often designed to utilize outright leverage and this limitation will not change for them but they will need to honor both the asset coverage test and VaR limit.

Rule 18f-4 VaR Limits and Limited Derivatives Users

Key VaR Parameters

Rule 18f-4 does not specify a particular VaR model that must be used but does require that the model be based on at least three years of historical market data. The Rule also requires that the VaR model takes into account significant, identifiable market risk factors as applicable, including equity price risk, interest-rate risk, credit spread risk, foreign currency risk and commodity price risk. The model must account for non-linear price characteristics of a fund’s investments, including positions with optionality. The model must also account for sensitivity of the market value of fund investments to changes in volatility.

Regardless of the model, Rule 18f-4 mandates two key parameters: time horizon for returns and confidence level.

The Rule mandates a 99% confidence level. However, the SEC permits different means of performing the calculation. For example, a fund could use a 99% confidence level or start with a lower confidence level and rescale up to a 99% confidence level.

The Rule also requires a 20-trading-day time horizon for measuring returns, but permits using daily returns that are scaled up to a 20-day return number.

Relative and Absolute VaR Tests

Rule 18f-4 establishes a relative VaR limit of 200% for open-end funds, which measures the VaR of the fund against a reference portfolio. In a simple example, a portfolio might have an absolute VaR of 10% and its benchmark might have a VaR of 5%. With those facts, the relative VaR of the portfolio relative to its benchmark is 200% and at the Rule threshold. Closed-end funds that have outstanding shares of a senior security that is a stock have a higher 250% threshold given that the preferred stock would inherently raise the fund’s VaR without taking into account any derivatives investments.

Selection of the reference portfolio is left to each fund. The fund can pick a designated index that is not leveraged, reflects the markets or asset classes in which the fund invests, and is not created or administered by an affiliate (unless widely recognized and used). If a fund’s investment objective is to track the performance of an unleveraged index, the fund must use that index as its designated reference portfolio. The designated index is not, however, required to be the same index the fund shows for performance comparisons in shareholder reporting or marketing materials. The fund can also use its own securities portfolio (i.e., holdings excluding derivatives) as its reference portfolio.

Relative VaR is the Rule’s default, but a fund may determine that a designated reference portfolio would not be an appropriate reference for purposes of the relative VaR test, taking into account the fund’s investments, investment objectives and strategy. If an absolute VaR approach is determined appropriate, the Rule establishes a 20% threshold for open-end funds and 25% for closed-end funds that have outstanding shares of a class of a senior security that is a stock.

In all cases, the fund’s derivative risk manager makes the determinations, conducts periodic reviews and reports to the respective fund board.

Monitoring and Back-Testing

Compliance with the thresholds must be monitored on a daily basis. If a fund exceeds its VaR thresholds for five consecutive business days, the fund has one business day to make a confidential report to the SEC. Another report is required to confirm that any such breach was remedied.

In addition, a fund must back-test at least on a weekly basis to evaluate how well the model anticipated the fund’s estimated loss. This feedback loop is designed to require funds to refine the model continually to give the model and the VaR limits integrity. In the proposing and adopting release for Rule 18f-4, the SEC articulated that, assuming 250 trading days in a year, a fund would be expected to experience a back-testing exception approximately 2.5 times per year, or 1% of the 250 trading days. If 10 or more exceptions are generated in a year from such back-testing, the SEC said that it would be statistically likely that such exceptions are a result of a VaR model that is not accurately estimating VaR.

Limited Derivative User Exemption

Rule 18f-4 excludes a fund from the requirements of VaR limits if it qualifies as a “Limited Derivatives User.” A fund qualifies if its “derivatives exposure” is no more than 10% of the fund’s net assets, based on the gross notional value of the derivatives (with certain adjustments and exclusions). A Limited Derivative User fund must also have policies to address its derivatives risk, but is exempt from the full requirements of the Rule including the prescriptive measures of a derivatives risk management program.

The technical aspects of the determination of the exemption’s availability are critical. For example, a fund may delta adjust notional amounts of options contracts. It may also exclude currency or interest-rate derivatives that hedge currency or interest-rate risks, but the hedges need to be directly associated with specific fund holdings. Abstract notions of hedging will not qualify. Even permitted hedges may not exceed the value of the hedged investments by more than 10%.

In addition, the Rule draws a wide perimeter around the population of instruments that are considered to be derivative transactions. For example, transactions that involve delayed settlement such as when issued US Treasury securities may only be excluded from this definition on two conditions. First, the fund must intend to settle the transaction physically (as opposed to transactions designed to roll forward or otherwise offset the exposure). Second, the transaction must settle within 35 days. The goal of these conditions is to distinguish forward transactions that involve a greater potential for leveraging.

By regulation, a Rule 2a-7 money market fund is even more limited—it may not invest in derivatives at all. However, instruments meeting the delayed settlement criteria remain eligible for money market funds (as long as all other Rule 2a-7 requirements are met) and require no coverage.

Rule 18f-4 also permits two different treatments for funds utilizing reverse repurchase agreements. One option is to treat all reverse repurchase and similar financing transactions as derivative transactions and therefore subject to the same VaR limits applicable to other derivatives. The other option is to treat such transactions akin to a borrowing and therefore subject to Section 18’s asset coverage requirements.

How Does Western Asset Utilize Derivative Instruments?

Derivatives are an integral part of many areas in the financial markets. Futures and options are the purest derivative securities, because their returns are tied explicitly to changes in the value of some other security, currency or index. Derivatives have been a particularly integral part of the fixed-income markets. Since its creation in the early 1980s, the swap market has become an important arena for all types of bond issuers and investors seeking to lock in forward borrowing rates and/or seeking economic exposure to forward rates. Currency forwards are, by some accounts, the most widely used financial instruments in the world. They can be used to hedge away currency risk while retaining certain market risks. Derivatives analysis has become a key component of fixed-income investment.

Derivatives can also be a valuable part of the portfolio management process. Western Asset primarily uses derivatives in an effort to add incremental value and to hedge or reduce risk. In conjunction with its traditional fixed-income management style, Western Asset generally uses derivatives in an effort to achieve the following objectives, in descending order of importance (subject to applicable investment policies, guidelines and restrictions for any particular client):

- Implementing portfolio strategy

- Restructuring portfolio return characteristics

- Anticipating or hedging changes in the term structure of interest rates and credit spreads

- Adjusting portfolio duration

- Capturing valuation opportunities

- Misvalued and/or distressed securities

- Buying or selling volatility

- Changing sector exposure

- Exploiting market inefficiencies

- Basis arbitrage

- Spread arbitrage

APPENDIX

Value at Risk Model Ownership and Administration under SEC Rule 18f-4

Rule 18f-4 is an Investment Company Act rule that applies to US mutual funds. Funds in scope are required to maintain a derivatives risk program and abide by Value at Risk (VaR) limits as a means of controlling derivatives and leverage risk.

The Rule requires maintenance of a VaR model which compares portfolio VaR to the VaR for the portfolio’s benchmark or selected reference portfolio (or in more limited cases, establishes an absolute VaR limit) for daily monitoring. In addition, the Rule requires back-testing to ensure the model continues to reasonably reflect the real world. If a portfolio goes over its designated VaR limits, immediate corrective action is required.

The calculation of VaR is not a simple and mechanical process. Effectively designing and utilizing VaR models requires an understanding of various assumptions and implications—there are elements of judgment involved.

VaR models require understanding of various assumptions and other elements subject to careful judgement regarding the exact approach required. However, a fund ultimately must look to one VaR model as its official model for Rule 18f-4 purposes.

There may be different results produced by different parties using different models and/or different underlying assumptions in calculating the VaR numbers. There always may be benefits of shadowing or comparing models, but we have to take into consideration that the Rule imposes limits and requires certain actions in a limited timeframe based on the official VaR model results.

By regulation, Western Asset, in its role as sub-adviser, cannot assume overall responsibility for a fund’s derivatives risk program. However, Western Asset can assist fund clients in complying with Rule 18f-4 VaR limits in one of the following ways:

- A fund could adopt Western Asset’s VaR model, in which case Western Asset would apply both that model and related limits to the fund; or

- A fund could use its own model and supply Western Asset with the output in a timely manner, in which case Western Asset would apply limits derived from that model to the portfolio.

Western Asset prefers the first option, but recognizes that for different reasons, a client may prefer to maintain their own VaR models and/or monitoring VaR via a third party vendor. Western Asset can accommodate either approach.

Each approach comes with its own implications. An overview of each approach can help inform discussions that Western Asset has with its US mutual fund clients in considering which approach to select.

Relying on Western Asset’s Value at Risk Model

There are two key advantages of Western Asset’s VaR model: knowledge of the instruments, the model and its underlying assumptions, as well as using the same model in day-to-day risk management. Both of these are critical in times of stress when a fund can approach or exceed VaR limits and when time is short to correct the issue, especially when markets are under stress.

Security set-up is crucial. A number of questions comparing model results are answered by reconciling security set-ups rather than differences in methodology. As the sub-adviser, Western Asset is well-positioned to understand the instruments and their attributes.

Knowledge of the model and its drivers will be extremely important if/when a fund is approaching or crossing the VaR limits. There is value in being able to validate before taking action and forcing trades to remedy. Being close to the model also helps determine what measures are needed to keep a portfolio under a VaR limit or repair an overage. VaR inherently stems from a quantitative model, so the interactions of all the inputs and variables/model assumptions, and the corresponding cause and effect of particular trades may not be immediately clear. Being able to make informed decisions—particularly in times of stress—may prevent unnecessary fund trades in the most difficult market conditions. That difference may facilitate Western Asset’s ability to address outages in the tight time frames required by Rule 18f-4. Using the Western Asset model will also lessen dispersion from proprietary funds, often a key concern of sub-advisory clients.

Rule 18f-4 requires regular back-testing to ensure the VaR model maintains integrity. Identifying circumstances when actual returns significantly deviate from forecast model returns leads to an ongoing evaluation of the model. There is judgment and expertise involved in this discipline. Western Asset typically reviews the efficacy of its model on a monthly basis. Other than regular updates to inputs, the model itself may not change frequently.

Western Asset has expertise with VaR modeling, estimation and usage, and worked with VaR limits in other regulatory contexts before Rule 18f-4 was established. The Firm built and maintains an in-house system, so it does not rely on third party vendors. There will be design decisions in how Western Asset builds and maintains its model.

If a fund delegates the VaR aspect of Rule 18f-4, Western Asset can provide transparency into daily VaR metrics on whatever frequency the client requests. The Firm can also provide documentation and support fund oversight and diligence efforts.

Fund clients may wish to maintain a shadow VaR model as a measure of independent oversight. Western Asset would work with such clients to mitigate the risk of large differences between the models, but Western Asset’s internal model would be the metric of record. In practice, clients with such capabilities may ultimately prefer to use their model as the standard but it is an option worth noting.

Fund or Fund Adviser Ownership of the VaR Model

For various reasons, funds may prefer to use a VaR model they develop and associated monitoring for Rule 18f-4 purposes. For example, fund complexes with multiple sub-advisers and multi-manager funds may prefer to maintain a single VaR approach at the fund level.

In these cases, Western Asset would maintain a shadow VaR for its internal purposes and/or coordinate with fund clients to obtain a regular feed of official VaR metrics. These measures would be necessary to permit Western Asset to effectively manage the fund within required VaR limits.

There are trade-offs to this approach. As noted above, there may be differences among Western Asset VaR results and the results from other models due to security set-ups and/or VaR methodology. Western Asset will not be able to validate fund client VaR results and will not have full transparency into the drivers or what actions are likely to have what results under the client’s model. When approaching or exceeding VaR limits, funds will either need to instruct specific remedial measures based on their knowledge of their VaR model or Western Asset will make its best educated guess.

There may be delays in the back-and-forth of communications and action, which are exacerbated in times of market stress. These delays may impact prompt resolutions, particularly if a client is relying upon another third-party service provider for its VaR model administration. Resolutions could take different forms for different fund clients with different VaR approaches resulting in dispersion.

Western Asset understands there are valid reasons for different approaches. There may be clearly “wrong” approaches; there may not be a single “right” approach. Being aware of the implications and either accepting or mitigating those risks is part of an informed decision-making process.

For fund clients that choose the second approach, Western Asset envisions the following framework to mitigate the risks involved:

- Advance diligence and periodic check-ins. Models may never fully match, but efforts can be made to minimize chances of big differences by working together when time or stressed markets are not an issue. The goal is not full reconciliation, but rather identification of obvious things that may be incorrect and a mutual understanding of key drivers or contributors. Given the possibility of changes over time, a periodic refresh could be helpful. Western Asset suggests a baseline check on at least an annual basis which includes an understanding of the top 10 drivers of the client’s VaR model. In addition, Western Asset would require daily VaR levels for ongoing comparison.

- VaR model principles. Western Asset believes that well-built VaR models will reflect similar “best practices.” Incorporating these foundational principles will help mitigate the risk of large variations. These practices include:

- All securities in the portfolio must be modeled. Some small positions can be approximated, but large positions or derivative positions, which can look small but contribute significantly to risk, need to be given a defensible security model.

- All material risks in the portfolio should be captured by the risk factors in the model. A risk model may not capture every possible relative value position, but if the portfolio return will be affected by a relative value position either intentionally or unintentionally, then the risk model needs to capture that factor.

- For fixed-income portfolios, a Monte Carlo model is generally needed as most fixed-income securities have a maturity making historical simulation impractical and parametric methods will not capture the non-linear behavior of many securities such as options or structured products.

- Western Asset model design. Western Asset has made design choices in building its internal VaR model. Fund clients can then compare Western Asset’s model with their own design choices or those made by their service providers. Western Asset’s internal models take the following approach:

- Monte Carlo simulations are generally required for fixed-income portfolios.

- Volatilities that are not overly reactive. Volatilities that are very low most of the time, but quickly jump higher after a market event, are undesirable. They can lead to forced selling at the market bottom and a false sense of security the rest of the time. Model volatilities should take a longer view. Western Asset suggests a minimum historical half-life of one quarter for factor volatilities and correlations.

- The model should capture idiosyncratic and/or default risks.

- The model should capture non-linear behavior by using factor distributions that have fatter tails than a standard normal distribution and by including non-linear payoffs for securities such as options or callable securities.

- Security set-ups. Many instruments will not present complexity, but instruments with certain features can require heightened care. Instruments with embedded optionality that can radically change their return behavior are at particular risk. For example, factor exposure of options can change materially if they are in or out of the money. Taking care to address this non-exhaustive list of instruments or those similar with these attributes can mitigate the risk of differences in model results:

- Options must at least use a delta that adjusts daily to market changes. For any material option positions, it is desirable to include convexity in the factor model or, better still, to fully evaluate the option in each Monte Carlo scenario.

- Other securities with non-linear payoffs such as callable bonds, mortgage bonds or tranched securities should contribute to appropriate convexity exposures if full evaluation is not practical.

- The model should look through any commingled holdings and to the underlying securities.