Stronger, Safer, Simpler: The Investment Case for Banks a Decade After the Crisis

Executive Summary

- A full 10 years after the financial crisis, the global bank regulatory jigsaw puzzle is nearly complete.

- Global bank regulation remains a key positive pillar for credit investors.

- “Lower-risk banking” business models are firmly entrenched.

- Bank managements, investors, regulators, rating agencies and politicians will reward banks as they return to basics with higher-quality earnings and less casino-like behavior.

- A meaningful rollback of regulations is unlikely, either in the US or globally, but expect to see existing rules applied with a lighter touch.

- We believe these reasons continue to warrant a meaningful overweight to banks globally with a preference down in the capital structure for the strongest US and European banks.

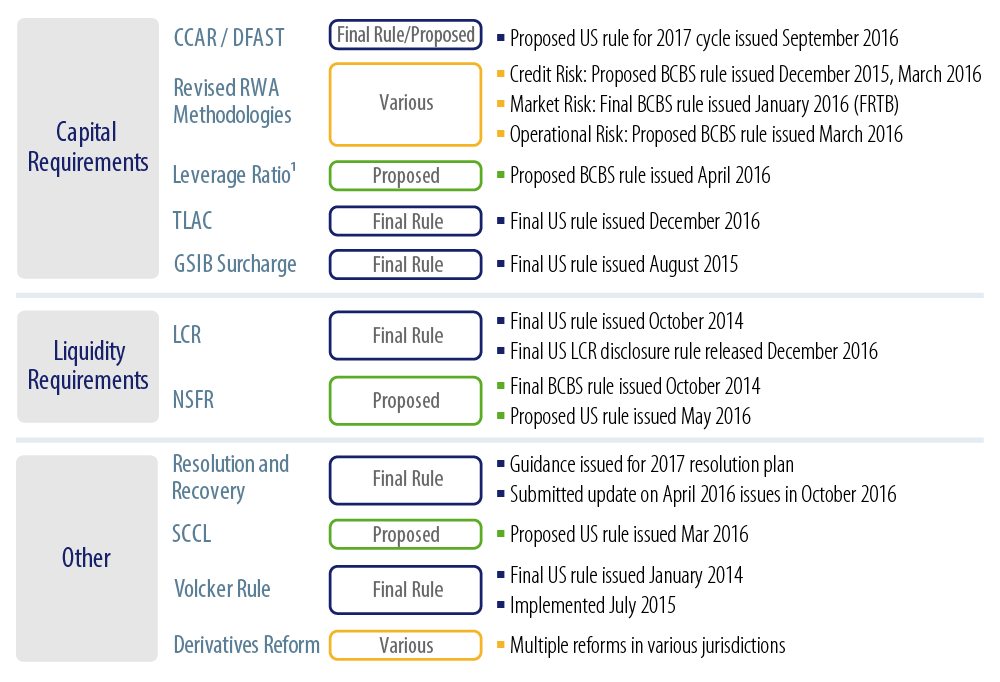

It was 10 years ago this month that we saw the start of a significant widening of spreads in bank bonds and the corporate credit markets more generally. Since then, bank regulation globally has played a critical role in transforming the business model from a casino-like venture into a less volatile and more profitable utility-like industry. Not surprisingly, after a 10-year crusade by regulators, we now believe that the regulatory jigsaw puzzle (Exhibit 1) is largely complete as lower-risk banking business models are well entrenched. In other words, regulators have achieved their two primary goals of ensuring another financial crisis is avoided, and shifting losses away from taxpayers and depositors to investors upon bank failure.

Regulators have learned painful lessons that rapid balance sheet growth and acquisitions tend to make banks much riskier, and that management teams will inevitably be tempted to find loopholes in the next series of Basel rules.

In this note we explain why we believe these painful lessons have made banks stronger, safer and simpler—and therefore more compelling from an investment standpoint.

Current Regulatory Jigsaw Puzzle

Stronger: Significant Improvement in Capital Levels and Liquidity

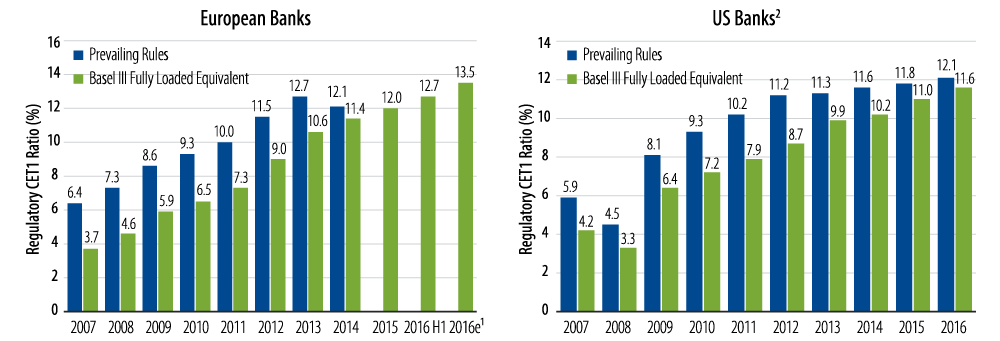

Driven by the much stricter Basel III post-crisis regulatory framework that requires banks to hold more and higher-quality capital, banks generally, and European banks in particular, have improved their fully loaded Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios to 13.5% by the end of 2016, compared with an estimated 3.7% in 2007 (Exhibit 2). In absolute numbers this means the largest European banks have increased their common equity capital bases by more than €700 billion between 2007 and 2016—an increase of almost 90% during that time frame.

Capital build at the US banks has been even stronger with $800 billion between 2008 and 2016, and the proportion of tangible common equity in capital bases (the highest-quality form of capital) increased from 26% to 54%. This means US banks now hold nearly 3x the tangible common equity they did in 2008. On the liquidity side, loan/deposit ratios have improved materially and the introduction of fresh regulatory liquidity ratios (the Liquidity Coverage Ratio and the Net Stable Funding Ratio) will provide an analytically more meaningful and sophisticated approach to ensure the resilience of banks’ liquidity profiles.

Evolution of CET1 Ratios

Safer: Judicious Supervision and Tightened Regulatory Framework to Lead to Lower Failure Rates

Judicious supervision and a tightened regulatory framework, together with the significantly increased balance sheet strength and considerably de-risked business models, have made banks much safer when compared with the pre-crisis world. While this means that bank failures will become less likely, regulators now have the tools available to achieve one of their key aims of shifting losses from taxpayers to investors. This is best evidenced by the way the relevant authorities have dealt with Spanish bank Banco Popular (see following case study). Under the new bank resolution regime in Europe, capital instruments (Additional Tier-1 securities as well as Tier-2 bonds) will be bailed in and a new class of senior debt will provide additional total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) in the form of bail-in senior debt or TLAC debt. In Europe, depending on the jurisdiction, TLAC debt will be issued in the form of non-preferred senior debt, typically in jurisdictions where banks do not have holding company (HoldCo) structures, or in the form of HoldCo senior debt which is structurally subordinated to operating company senior debt.

As a consequence, bank credit investors can no longer count on taxpayers to bail them out as future recoveries will very much depend upon where creditors sit in the bail-in “waterfall.”

Banco Popular: Moving from Theory to Practice

On June 7, 2017, the Single Resolution Board, the authority tasked with resolving failing banks in the eurozone, announced that it was taking resolution action against Spanish bank Banco Popular which involved the transfer of ownership of the bank to Banco Santander for a nominal €1. This followed the determination by the European Central Bank (ECB) that Banco Popular was “failing or likely to fail,” driven in particular by “the rapidly deteriorating liquidity situation” of the bank. In our view, it was this escalating liquidity crunch that led to resolution action being taken midweek, rather than over a “resolution weekend” as everyone has come to expect.

Of the resolution tools available, the authorities chose the “sale of business tool” which “should enable authorities to effect a sale of the institution or parts of its business to one or more purchasers without the consent of shareholders,” as stated in the Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive.

As a result, all of Banco Popular’s existing equity, its AT1 issuance and its Tier-2 bonds were all effectively wiped out by being written down to zero. Senior obligations were being kept whole and became obligations of Santander. From the authorities’ point of view, this resolution action successfully secured the continuation of the critical functions of Banco Popular—retail and small and medium enterprises (SME) deposit-taking; SME lending; and payment and cash services—as well as avoiding adverse effects on financial stability that would arise from a disorderly collapse or even a standard corporate liquidation. As such, we see the case of Banco Popular as a successful application of the rulebook in practice.

Simpler: Incentivized by Regulation and Investors Rewarding Simpler Business Models

We are confident that the bank resolution framework has successfully dealt with too-big-to-fail risks for financial stability. We also believe that regulation aims to encourage investors to reward simpler bank business models and that this trend is well entrenched globally.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) implementation methodology for identifying Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) is a specific example of how “systemic importance” is penalized. The methodology is based on 12 indicators that fall under five broad categories—size, interconnectedness, substitutability, complexity and cross-jurisdictional activity—and, depending on the score, can lead to additional capital requirements of up to 3.5%. This surcharge has to be met with the highest-quality form of capital, common equity Tier-1. Of the 30 identified G-SIBs, 13 are in the EU, eight in the US and four in China. The highest additional capital buffer currently applied is 2.5% for Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase, followed by Bank of America, BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and HSBC with 2%. On one hand, this additional capital requirement means that it is less attractive for banks to be large and complex; on the other hand, it also means that there is more capital available in case one of these globally systemic banks gets into difficulty.

Beyond the regulatory incentives, we also believe that management teams intrinsically have a strong desire not to be “next” when it comes to getting a bank into difficulty as memories of the crisis are still fresh and both management and investor incentives are better aligned today.

Regulatory Jigsaw Puzzle and Journey Back to Basics Nearing Completion

In the prior two decades before it was exposed as high risk and unsustainable, the banking business model essentially had morphed into a casino-like business that emphasized size, scale, high growth, diversification, globalization, transformational acquisitions with opportunistic managements exploiting questionable or weak assumptions, poor accounting practices, limited disclosure and ambivalent regulation. Size, scale and diversification were viewed as false safeguards fueling double-digit asset growth, AA credit ratings, excessive stock prices, overly generous credit spreads and bad business practices. In reality, the largest, most diversified and fastest-growing banks ended up having the most misadventures and consequently the most expensive government bailouts.

The decade-long journey back to basics has taken us from an under-regulated industry growing excessively to an over-regulated one with a few well-run giants with stronger balance sheets, lower growth, better underwriting, more conservative capital management, better regulation, lower legal and operating expenses, fewer acquisitions and less non-bank competition.

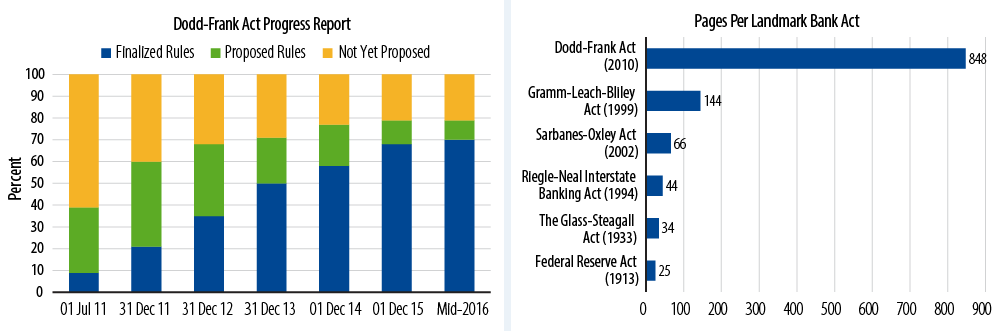

This journey and its implementation are now largely complete (Exhibit 3). While increased regulation has come at a financial cost—the negative revenue impact combined with higher regulatory costs is estimated at around $20 billion for the 20 largest US banks—this is a price well worth paying, especially from our perspective as bond investors. To give a specific example of how intrusive the supervision of banks has become, M&T Bank in 2016 faced 27 different examinations from six regulatory authorities, with examinations occurring in 50 out of 52 weeks.

Bulk of Regulatory Rules Now Finalized

Risks of Meaningful Rollback in Regulation Overstated

In Europe, regulators, authorities and the banking industry itself are still very much focused on solving “legacy” issues surrounding non-performing loans, which still stand at around €1 trillion for EU banks, and fixing inefficient banking system structures across many European countries. As we understand it, any change in regulation in Europe should be seen as the regulator “rounding off rough edges.” In other words, making different parts of the quickly rolled-out regulatory framework more coherent rather than interpreting these as regulatory rollbacks.

When compared with Europe, US banks are generally in better shape in terms of fundamentals, as the system has overcome most of its legacy issues and the new Trump administration identifies deregulation as a major policy focus. As a result, we accept the possibility of gradual regulatory rollback of US regulation, and a lighter touch when enforcing existing rules. While some limited overhaul of Dodd-Frank is possible at the margin, Democrats are unlikely to allow broader repeal of the act. In contrast, the recent Treasury Department proposals for financial sector reform generally do not require congressional approval and should be successful in simplifying regulatory burdens and costs faced by banks, helping to modestly bolster their profits. We doubt, however, that the White House administration can dramatically impact US bank earnings or their business models over the next few years.

Improved Conditions Not Yet Captured in Ratings: Positive Ratings Migration Expected

Banking has gone from the most overrated industry to arguably one of the most underrated. You can place blame on many participants for the global financial crisis, including the global banks. One group often singled out for its part is the credit rating agencies, criticized for their generous rating of the full spectrum of entities—from the banks themselves to their investment conduits. Inevitably, the pendulum has swung back, perhaps too far in some cases. Large global banks are arguably much safer today than they were prior to the global financial crisis, when they were rated much higher.

We argue that banking is one of the few industries to have become less risky over time without being upgraded from meaningfully lower levels and we would not be surprised to see these apparent inconsistencies corrected with future rating upgrades. It remains our suspicion, however, that rating agencies may be punishing US and UK banks for the past instead of rating them for the future. For example, when we look at the spectrum of ratings from Moody’s, we are puzzled why US bank ratings have dropped from Aa1 in 2007 for both Bank of America and Citigroup to unsupported implied standalone ratings of Baa2 for both banks. Interestingly enough, both Bank of America and Citigroup have senior unsupported ratings eight notches below the US sovereign Aaa rating and five notches below the senior debt ratings of Aa3 for Santander Chile. Likewise, the UK’s Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) was downgraded by Moody’s from Aa1 in 2007 to Baa3 currently and its senior ratings are also eight notches below the Moody’s rating of Aa1 for the UK sovereign.

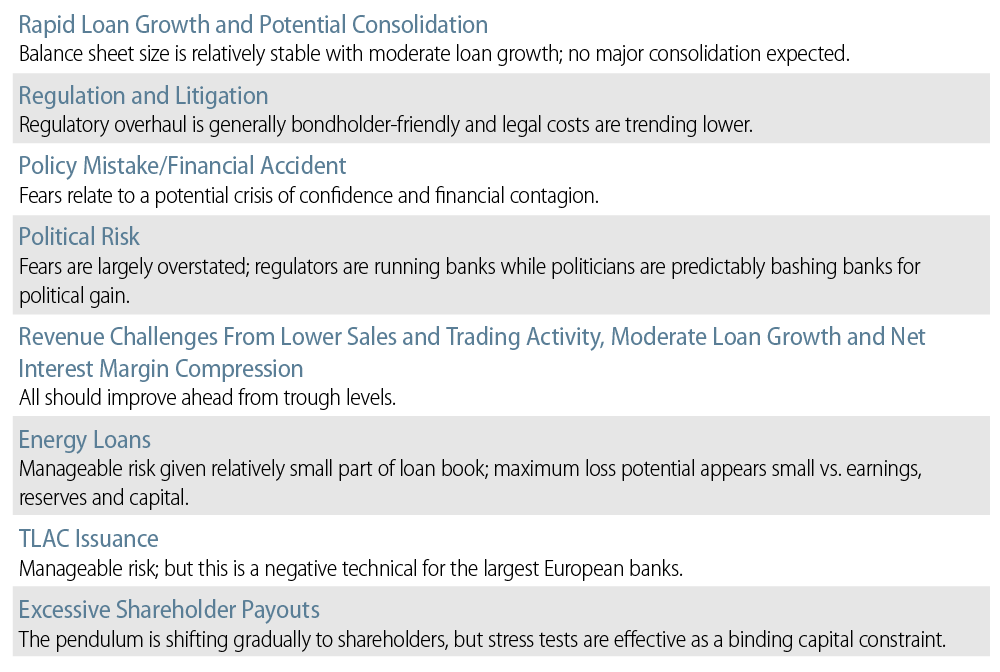

De-risked Does Not Mean No Risk

While the regulatory and banking communities have achieved significant progress in making global banking safer, there remain several risks to banks. In Exhibit 4, we focus on the smaller subset of key risks to bondholders.

“It’s the Economy, Stupid” ~James Carville, 1992

Economic Recession—Major and Most Important Risks for Banks

Investment Conclusion

In our view, banks have become stronger, safer and simpler over the last 10 years. We believe that the secular de-risking of the global banking business model has been successful, and its regulatory jigsaw puzzle is largely complete. The new, simpler banking business models are well entrenched given the reaction to damage wreaked by the previous incarnation. Investors, taxpayers, rating agencies, politicians and of course regulators, were all impacted.

Furthermore, additional positive catalysts would include:

- US bank earnings in 2017 should surpass record levels,

- Upward ratings pressure (e.g., Moody’s US bank ratings and UK HoldCo ratings), and

- Benign technicals and attractive valuations.

In summary, we believe the pieces of the global regulatory jigsaw puzzle are nearly all in place. Global bank regulation remains a key positive pillar for credit investors, and “lower-risk banking” business models are now firmly entrenched. We expect that bank managements, investors, regulators, rating agencies and politicians will reward banks as they return to basics with higher-quality earnings and less casino-like behavior. We believe a meaningful rollback of regulations is unlikely, either in the US or globally, but expect to see existing rules applied with a lighter touch. These reasons, in our view, all support Western Asset’s intentional overweight to banks globally with a preference down in the capital structure for the strongest US and European banks.