Headline retail sales rose just 0.3% in November, with no revision to the October estimated level. We and other analysts customarily focus on “control” retail sales, which excludes sale of vehicles, gasoline, building materials and restaurants, sectors that are especially volatile in the short-term and which also are frequented by businesses as much as consumers. The more “consumer-oriented” control sales measure actually declined by -0.1% in November, with a -0.1% revision to the October level.

What made these soft prints even more noteworthy was the fact that related goods prices rose again in November. Core goods prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 0.9% in November, only slightly less than the 1.0% rise in October. In other words, in real terms, control retail sales declined noticeably in November.

A month ago, we deprecated the strong sales gains reported for October. Between price effects and increases at store types that had seen sales declines in September and earlier, we asserted that the October report was more scattered than the headline readings suggested. Nevertheless, when consumer spending data for October were released two weeks ago, real consumption of goods saw decent October gains.

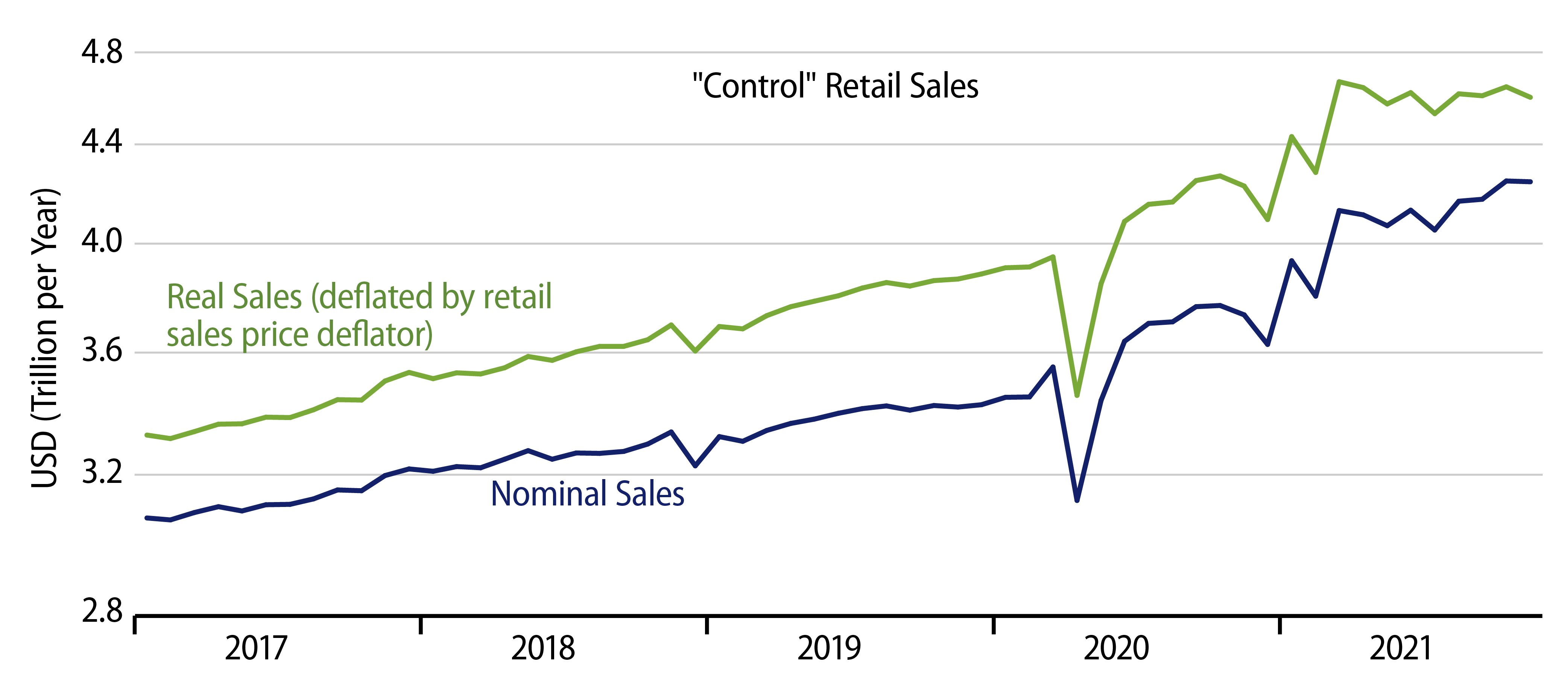

Suffice it to say that today’s data tilt back toward our assertion that the October sales gains were not indicative of underlying trends. As you can see in the chart, even in nominal terms, sales growth has been only halting since March, following a 1Q spurt. Allowing for price effects, real sales have been on a slightly declining trend for the last eight months.

When the economy was partially reopening last year but various service sectors were still operating under heavy restrictions, consumer spending on goods surged, partly to make up for purchases NOT completed during the shutdown and partly as consumption shifted from (unavailable) services to (available) merchandise. Since then, as reopening has spread—sort of—to service sectors and as appetites for goods have been largely sated, spending has begun to shift back to services. That is, real goods spending has languished, while services spending has moved gradually but steadily higher.

In contrast, consensus views have been that accumulated savings (unspent stimulus checks) would be unwound, driving goods spending further upward. This has not happened, at least not as yet.

The sluggishness in real consumer spending on goods is supportive of our inflation story. In a true, sustainable inflation, real spending grows alongside higher prices, as monetary policy is driving sufficient spending growth to accommodate both. In the current environment, based on presently available data, it looks as though recent increases in goods prices have come at the expense of growth in real sales and output. Spending is not growing fast enough to allow both higher prices and rising real activity levels. This suggests, for now at least, that when supply pipeline pressures peak and begin to ease, price increases will cease.

Granted, the situation is fluid, and there are a lot of moving parts. But this is our “assemblage” of the parts that are presently available.