The number of catastrophic events has clearly been on the rise globally. According to the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, reported economic losses from earthquakes, floods, hurricanes and other events have surged to $2.9 trillion over the last two decades—an increase of 151% compared with the prior 20-year period. If geophysical events (tsunamis and earthquakes) are excluded from the mix, the economic toll was the heaviest on the US, which had losses representing 42% of the total experienced over the past two decades—almost twice the damage experienced by the runner-up, China.

As the season of natural disasters approaches, it is worth examining the impact that such events have on municipal debt related to affected issuers.

Though there have been bond ratings downgrades—attributable to storms such as Katrina and Harvey, and in the case of the Paradise, California, wildfires—they have been far from pervasive. In fact, we have been unable to identify any default that resulted from a disaster.

Western Asset recently researched the spread behavior of a sample of bonds. This study revealed that, with the exception of lower-rated credits in disaster-prone areas, spreads have been minimally affected. Interestingly, on occasion a single event will drive spreads higher on one credit, while leaving others unscathed. Ultimately, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimburses losses on a scale that runs from 75% to 90% or more. With additional support from private insurance and state aid contributing to recovery efforts, most issuers will regain their footing but will be hard-pressed to improve credit quality above pre-disaster levels.

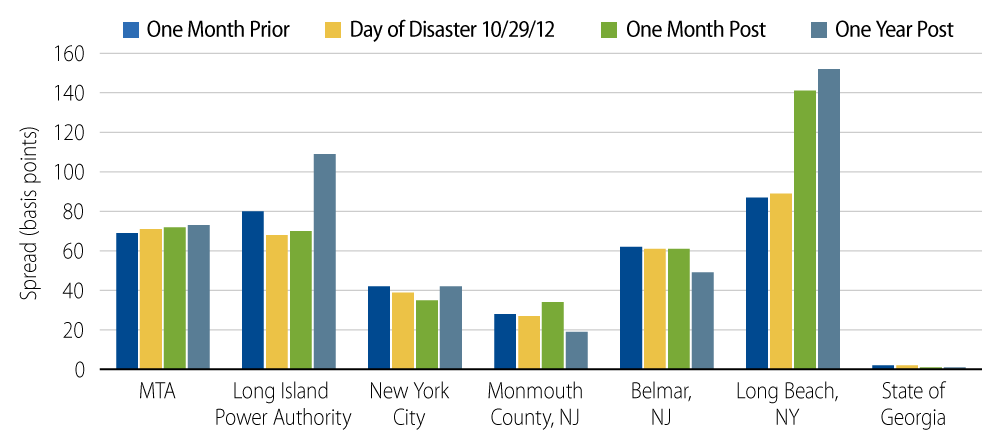

The chart below supports those conclusions, depicting the behavior of certain bonds following Superstorm Sandy’s arrival in late October 2012. As you can see, despite being hard hit, the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the Long Island Power Authority (LIPA), and New York City’s general obligation debt barely registered any storm impact, though one year later LIPA’s credit quality suffered, as it faced politically motivated organizational changes. Affected communities in New Jersey, however, were divided in their response to Sandy, with Monmouth’s spread increasing by 25%, but Belmar’s holding steady. Belmar’s spread remained unchanged despite Moody’s credit outlook revision to negative. Interestingly, Belmar, a shore community, is actually located in Monmouth County, yet Monmouth bore the brunt of the disaster from a credit perspective. One year post Sandy, spreads for both of these credits are less than they were prior to the disaster. On the other hand, the City of Long Beach, already credit-challenged with its limited liquidity and low Baa3 rating, experienced significant widening of over 50 bps immediately following the storm, where it remained. An unaffected Aaa rated bond for the State of Georgia was included to determine any general market effects and none were evident.

In conclusion, Western Asset has generally observed that as threatening as natural disasters can be, their impact on the municipal arena remains fairly muted.