Private-sector employment rose by 164,000 in December, partially offset by a -55,000 revision to prior months’ employment estimates. Average workweeks declined more than employment rose, so that total hours worked (jobs times workweeks) declined by -0.2%. Average hourly earnings rose by 0.4% for all workers and by 0.3% for production workers (those workers actually paid by the hour).

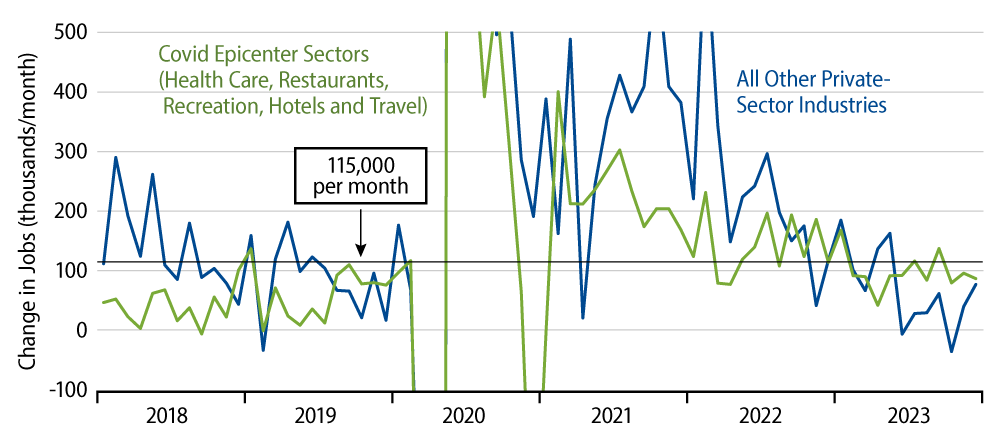

Generally, the December report was similar to what we saw last month. The November report showed a 150,000 gain in private-sector jobs, with -61,000 of downward revisions, so the net employment gains for December were slightly better than those for November. Furthermore, less of the December job growth was concentrated in sectors previously hard-hit by the Covid shutdown than was the case in November. As you can see in Exhibit 1, job growth outside the Covid “epicenter” sectors totaled 77,000 in December, after averaging only 20,000 per month over the previous six months. As of now, this bounce in “other” sector growth looks like a random blip within a decelerating trend, but who knows for sure?

Also, the November job gains were overstated by 30,000 due to the cessation of the UAW strike. So, the December job gains look even better relative to November upon this adjustment.

On the other side of the ledger, workweeks had bounced in November compared to the declines reported for December, so the -0.2% December decline in total hours worked was much softer than the 0.4% gain reported for November. However, the December gains in hourly wages were a bit better than what was reported for November. On net, it is likely that private-sector wage incomes rose 0.3% in December, after a 0.6% gain in November.

So, December saw better tone to job growth, but softer growth in overall employment conditions (slower growth in total earnings). You can make your own call as to which is more important.

We should also note that the downward revisions to previous months’ job data continued a pattern. Every month of 2023 has seen significant downward revisions to prior months’ growth. We can’t recall a string of such uniformly negative revisions. We now have “final” data through October, and the average revision through the first 10 months of the year is -55,000. Granted, those revisions are already reflected in the chart, but if you have been focusing only on the headline job growth number this year, you have been regularly overstating the strength of the reports by 55,000 jobs per month (and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has already previewed a downward benchmark revision of an additional couple hundred thousand to be announced next month.)

Now, even with those revisions, the pace of job growth is still decent. And even with the declines in average workweeks, total hours worked were still growing at an average rate of 1.2% per year in 2023 and at an annual rate of 0.7% in 2H23, down only modestly from the 1.5% growth trend seen prior to the pandemic.

So, no, labor market activity is not weak, but we would assert that it is not as strong as the headline job growth data would suggest, and the apparent deceleration in job growth bears watching. Continuation of this decelerating trend in 2024 would become a major story for the financial markets.