Real GDP grew at a 2.8% annualized rate in 3Q24, about the same as the 3.0% rate reported for 2Q. Nominal GDP grew at a 4.7% annualized rate, so that the price index for GDP registered 1.8% annualized inflation in 3Q. This index includes prices for all goods, services and structures produced within US borders.

Prices for the consumer spending portion of GDP (Personal Consumption Expenditures or PCE) rose at a 1.5% annualized rate in 3Q. The Federal Reserve (Fed) has been targeting “core PCE” inflation, that is, consumer inflation excluding food and energy prices, and that measure rose at a 2.2% annualized rate. In response to Fed Chair Powell’s comments that reported housing costs have technical issues, we have been tracking a core inflation measure that excludes housing costs as well as food and energy. That measure rose at a 1.6% rate in 3Q, well below the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

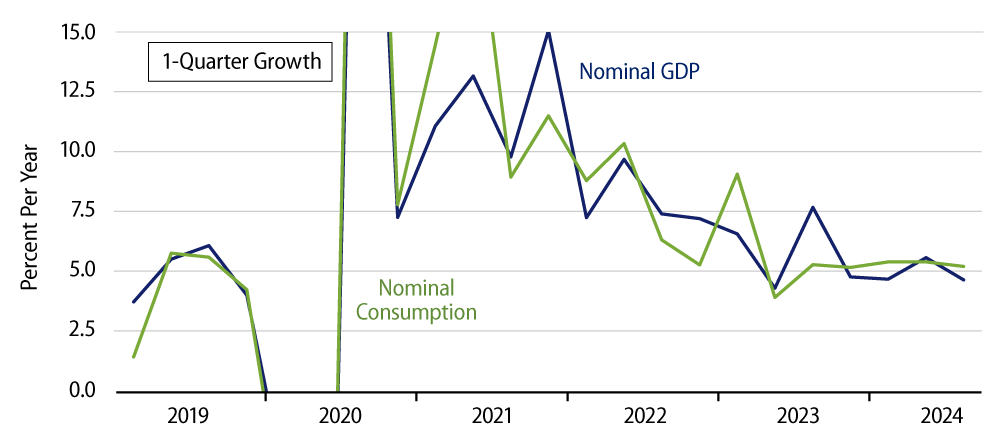

We track growth in nominal GDP as the ultimate driver of inflation and as the ultimate gauge of the effectiveness of Fed policy. Nominal GDP measures the pace of total spending in the economy, and if spending growth is not sufficiently rapid, real growth and inflation cannot coexist. As you can see in the Exhibit 1, nominal spending growth did indeed soar just after the Covid shutdown, and it has been decelerating ever since.

This is a telling indication that Fed policy has worked to constrain inflation on an ongoing basis in recent years. Notice that over most of the last two years, nominal spending growth has maintained the same rate seen prior to the pandemic. We think this indicates that inflation will indeed sustain at rates comparable to those seen prior to the pandemic. The 3Q rate of growth in nominal GDP was right in line with this.

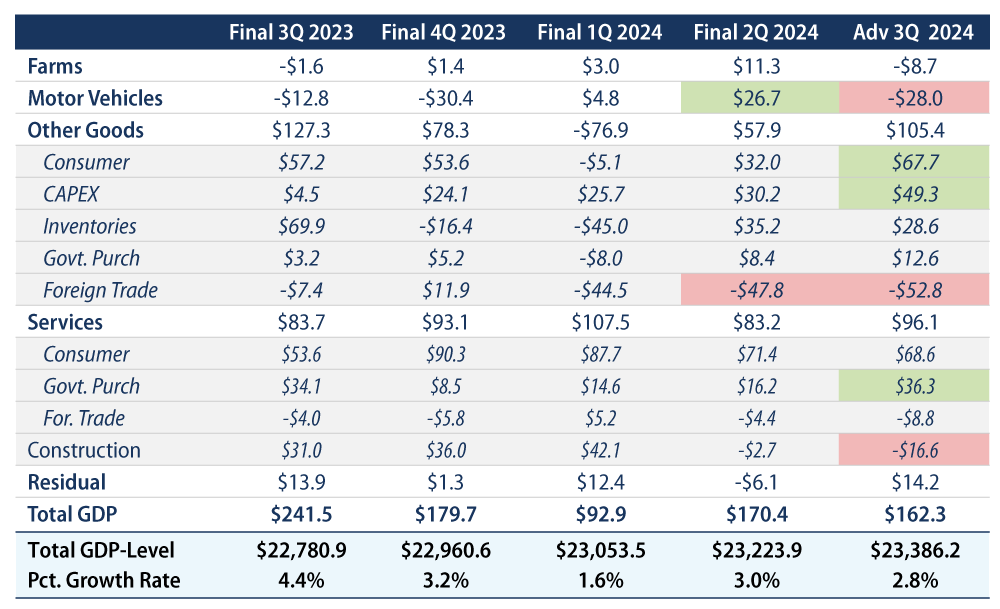

As for the sources of 3Q real growth, Exhibit 2 breaks down GDP growth according to goods, services and construction. (“Goods” includes manufacturing, mining and related industries.) We think this provides a good perspective on where growth is occurring—and where it is not. For goods production, we also break out farms and motor vehicles, the latter because of its often disparate performance relative to the rest of the economy. Sectors showing especially rapid growth in 2Q or 3Q are shaded in green, while those that are especially weak are shaded in red.

Indeed, motor vehicle production was reported as declining sharply in 3Q. This followed a similarly sized increase in 2Q. What is happening there is that the timing of the model-year shutdown for vehicle production is changing, and government seasonal adjustment factors have not yet adapted to this shift, hence the offsetting swings in 2Q and 3Q.

Elsewhere, consumer spending on goods rose nicely in 3Q, after softness earlier in the year. This is right in line with our previous analyses of retail sales growth. Business investment in equipment (CAPEX) was also particularly strong in 3Q. However, much of this investment was in imported equipment, which was one source of the big negative contribution to growth from foreign trade in goods.

3Q growth also got a sizable boost from government purchases of services. More than half of that increase was in defense spending and would appear to reflect assistance to Ukraine and Israel. State and local payrolls also saw a modest increase.

Meanwhile, construction contributed negatively to 3Q growth, reflecting declines in both residential and nonresidential construction spending.

Notice that much of the GDP growth occurred in goods production. We find this odd given that manufacturing accounts for the bulk of domestic goods production and factory output has seen essentially no growth over the last year. Still, that is what the GDP data proclaim.

All in all, a decent real GDP gain and the restrained growth in nominal spending augurs well for continued restraint in inflation.