The Reopening’s Impact on Growth, the Yuan and CGB Yields

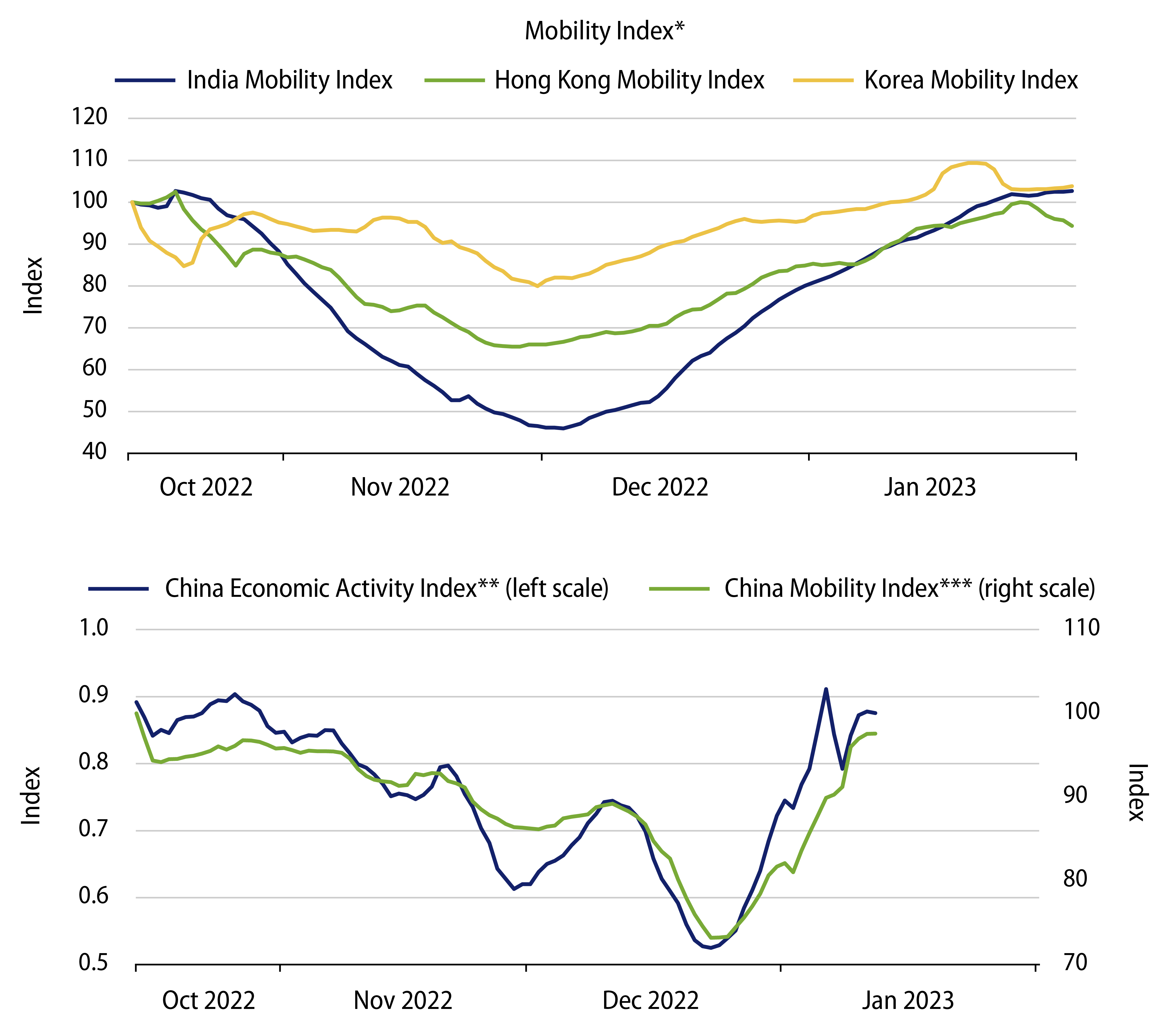

In late December 2022, China unexpectedly abandoned its Zero-Covid Policy (ZCP), which had been in place for almost three years. The abrupt dismantling of ZCP mobility controls surprised most market participants and COVID-19 then swept through China’s population of 1.4 billion people at an unprecedented speed and scale. Within two weeks, 80% of the population in China’s major cities were infected by the virus. While the wildfire spread of the disease came at a high human cost in terms of deaths and severe illness for the elderly and unvaccinated segments of the population, the younger and healthier folks have mostly recovered from their initial bouts of Covid infection and have since acquired “herd” immunity. This enabled most people to return to work and resume their pre-pandemic activities after the Lunar New Year holidays. Given that the world’s second largest economy had economic activity restrained for such a long period by ZCP controls, the magnitude of the cyclical economic recovery resulting from pent-up consumer demand and the resumption of pre-Covid economic activity should not be underestimated—including its beneficial impact on Asian countries with strong linkages to China’s economy. That said, this strong cyclical rebound should also be assessed against a backdrop of formidable secular challenges that China continues to face, summarized by the three Ds: demographics, debt and deglobalization.

Xi’s Policy Focus Is to Boost the Economy

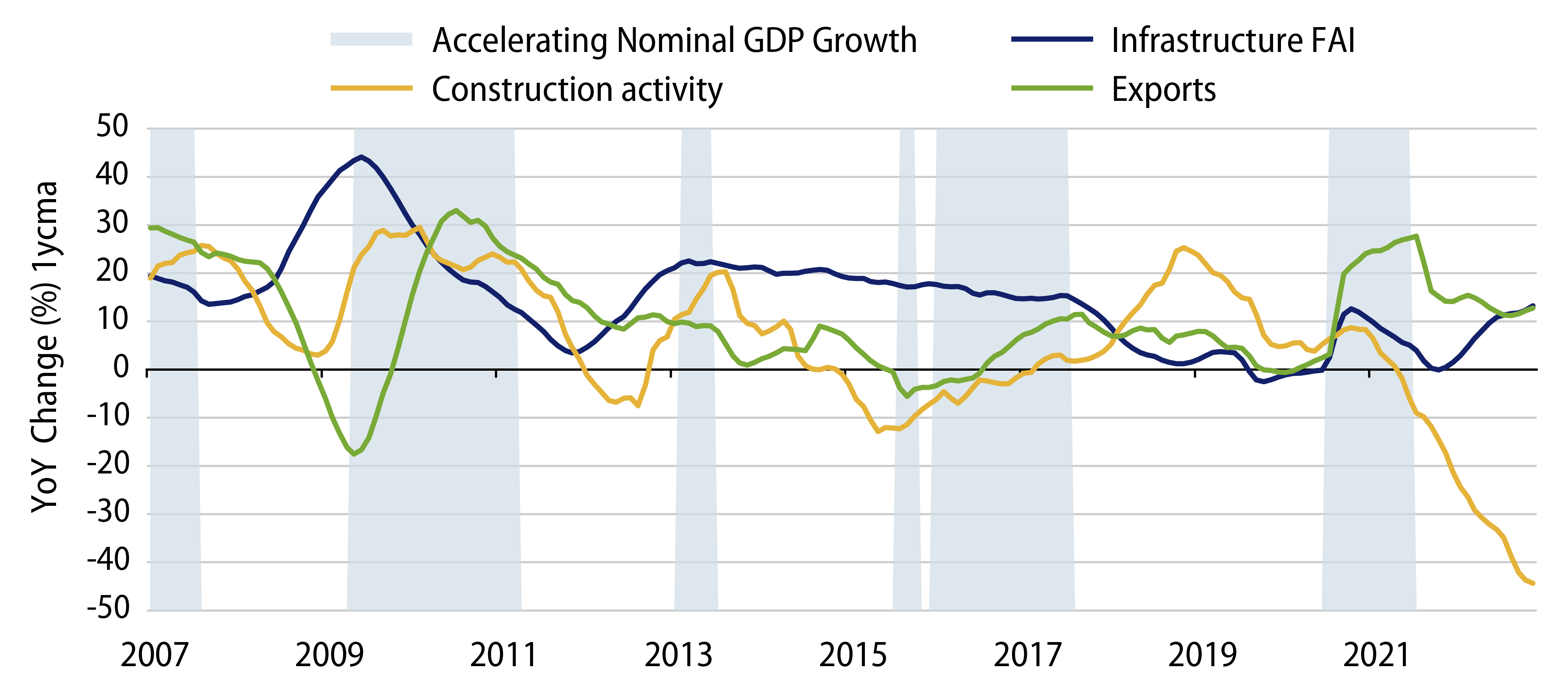

President Xi has secured an unprecedented third term and reviving China’s economic growth has become the top priority for his economic team. As a consequence, Chinese authorities have ratcheted up the firepower on policy measures to underpin the economy including fiscal pump-priming, a reversal of the crackdown on Big Tech and supporting the all-important property sector (Exhibit 3).

Reviving the Property Sector Is Crucial for Longer-Term Growth

Property investment is a big-ticket purchase that requires aspiring homeowners to have confidence in their long-term job security and a favourable view of the economy. Currently, there are a number of headwinds hampering consumer confidence in China. These include the unclear longer-term economic outlook, deglobalization and high youth unemployment. The high-profile collapse of Chinese real estate developers and significant declines in apartment prices have also cast doubts on the investment thesis of perennially rising property prices.

However, Chinese consumers have a high savings rate, limited channels for other investments and considerable headroom for rural to urban migration. Further, the Chinese government has an array of levers (macro-prudential and administrative measures) in the property market with easier monetary policy support. In recent months, a concerted rescue package has been rolled out, consisting of explicit liquidity support for higher-quality and well-managed developers, additional demand-side easing measures (particularly for upgrading demand), and stronger efforts to facilitate home delivery. Coupled with the rapid post Covid reopening, these substantial measures should arrest the current downward slide and stabilize property prices. A gradual cyclical recovery in property sales and prices is our base case scenario, although the cautionary scenario of Japan’s multi-decade decline in real estate prices following the bursting of the property bubble in the early 1990s cannot be ruled out.

The Implications for the Chinese Yuan

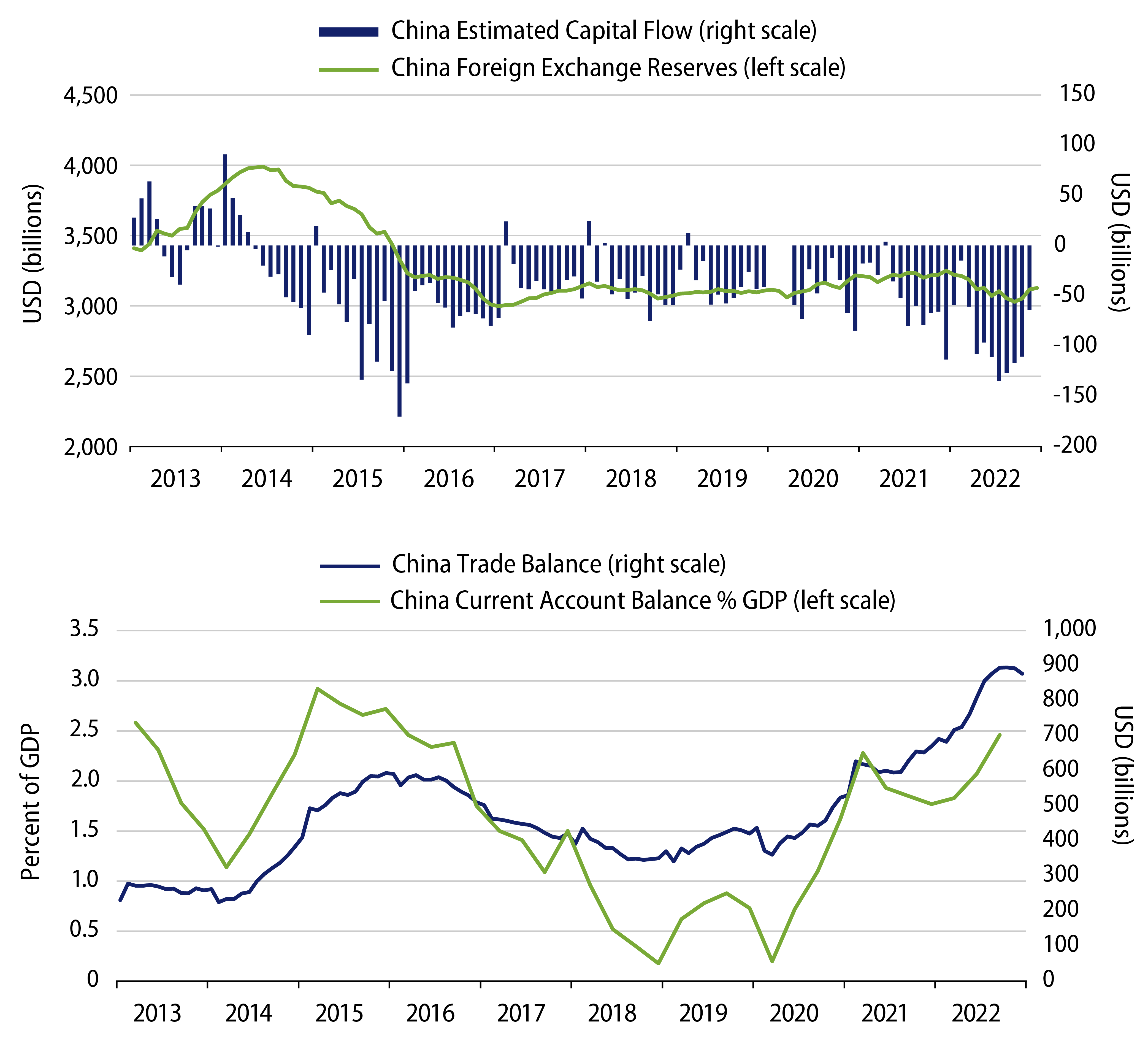

The Chinese yuan (CNY) has rallied sharply versus the US dollar since the start of 2023 on optimism over China’s rapid reopening, a benign US inflation/Federal Reserve backdrop and broad US dollar softness. However, compared with the other Asia foreign currency (FX), the yuan is among the weaker performers. This suggests that international investors have not piled back into Chinese financial assets in a meaningful way but shorts/substantial underweights have been covered or reduced.

We believe that China’s reopening, while attracting some foreign portfolio flows, will also have a weakening impact on China’s external accounts. China’s current account balance has improved substantially in the pandemic years to more than 2% of GDP in 2022 from less than 1% in 2019. This is due to the absence of international travel and no Chinese overseas M&A activities during the pandemic period. The resumption of outbound Chinese tourism will likely lead to a leakage of foreign reserves, although China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) will be more efficient in managing illegal outflows. Chinese overseas M&A activities, especially for Western companies, are unlikely to resume meaningfully in the hostile international environment of “on-shoring” and “friend-shoring.” Further, developed economies are experiencing an economic slowdown due to central bank tightening and the Russia-Ukraine conflict—these headwinds are likely to shrink China’s trade surplus in 2023. Hence, the softening of the country’s external accounts may limit the upside of the CNY strength despite investor optimism over the strong economic recovery.

Implications for Chinese Government Bond (CGB) Yields and Interest Rates

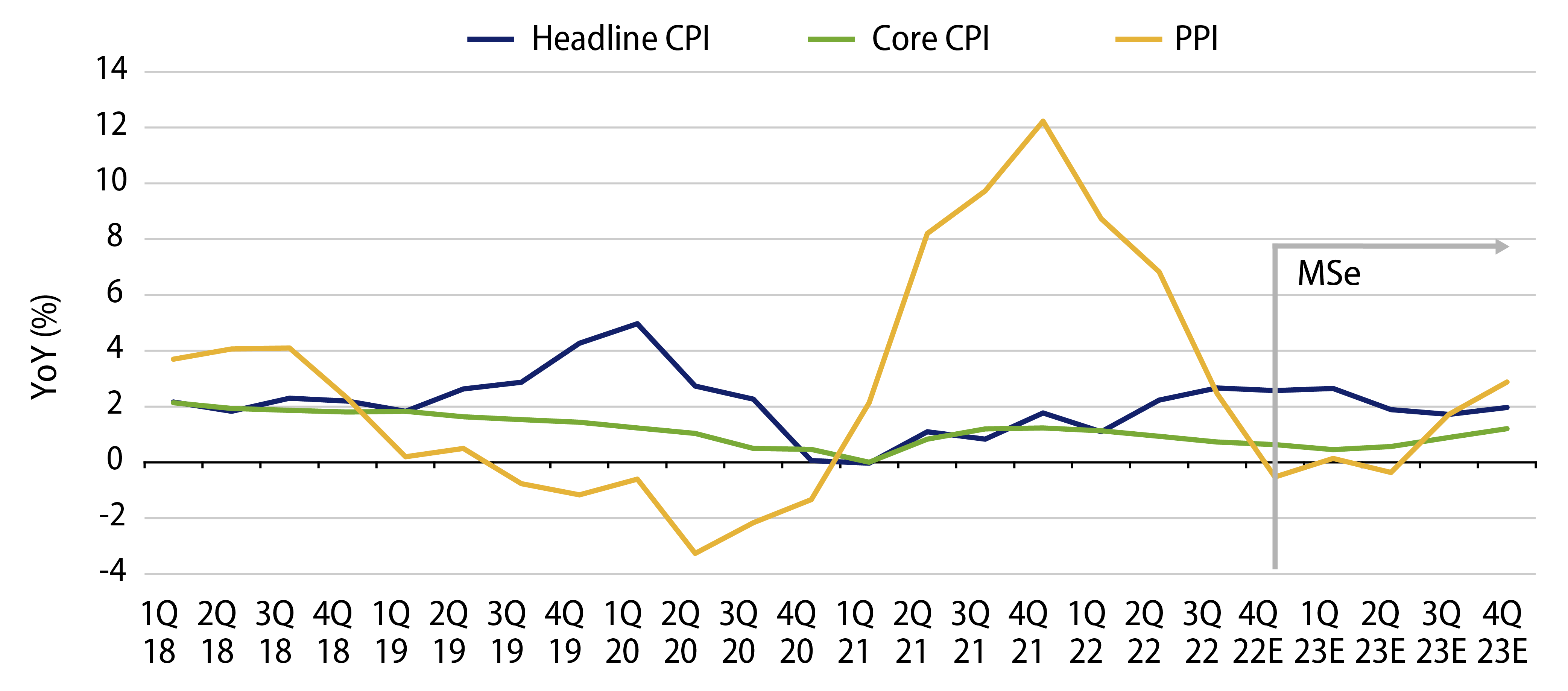

Yields on CGBs have bucked the trend of sharply higher global bond yields in 2022. Given the benign inflation outlook (Exhibit 6), we do not expect a significant rise in CGB yields due to the reopening. Unlike the rest of the world, the post-Covid impact on China’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) is likely to be muted, given that the share of services in the Chinese CPI basket is much lower (versus US CPI), and that Chinese food price pressures are likely to moderate from 2022’s high base with improving pork supply. In addition, limited consumer stimulus, China’s resilient domestic supply chains, the weak starting point of employment market and salary expectations altogether suggest that a sharp climb in CPI upon reopening is not our base case. We also expect muted Producer Price Index (PPI) reflation, as slowing global growth will likely put a lid on commodity prices, while domestically, the sluggish property sector will not lift commodity prices materially in 2023.

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) will likely keep China’s yield curve positively sloped so that Chinese banks, which are the traditional buyers of 3- to 5-year bonds, are incentivised to invest into the higher expected supply of CGBs and Local Government Bonds (LGBs). In particular, local governments derive a substantial amount of their revenue from land sales, and the stagnant property market has been a major strain on their finances.

Foreign ownership of onshore CGBs had declined significantly last year, to less than 10% of the total CGB market. This means that the Chinese bond market remains dominated by domestic investors including Chinese banks, pensions and mutual funds. The low sensitivity of CGB yields to global interest rates has demonstrated CGBs’ strong diversification attributes within a global government bond portfolio—and we believe that the low correlation will continue.

Investment Implications for Asia Economies and Commodity Markets

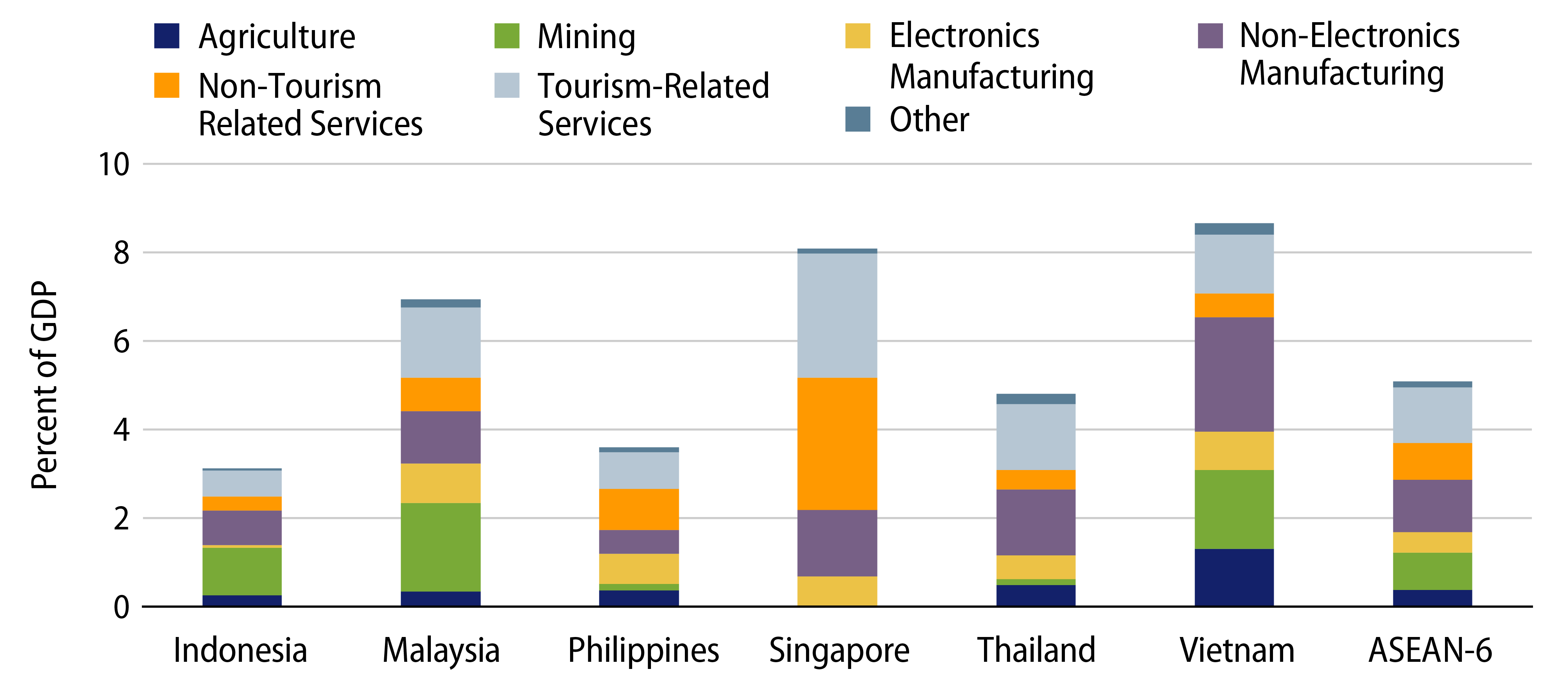

Asia economies are the key beneficiaries to China’s reopening. In particular, Chinese tourists are the major contributors to the global travel market. We expect Asian economies, including Thailand, Vietnam and South Korea, will see the most benefit from the return of Chinese tourists.

In terms of implications to the commodity market, the first-order impact of the revival of Chinese consumption and activity is likely to be higher global energy demand and prices (e.g., crude oil and coal). The second-order positive impact on metals (e.g., copper and iron ore) and building material prices (e.g., cement) will likely come into effect when the Chinese property market and infrastructural projects stage a meaningful recovery.

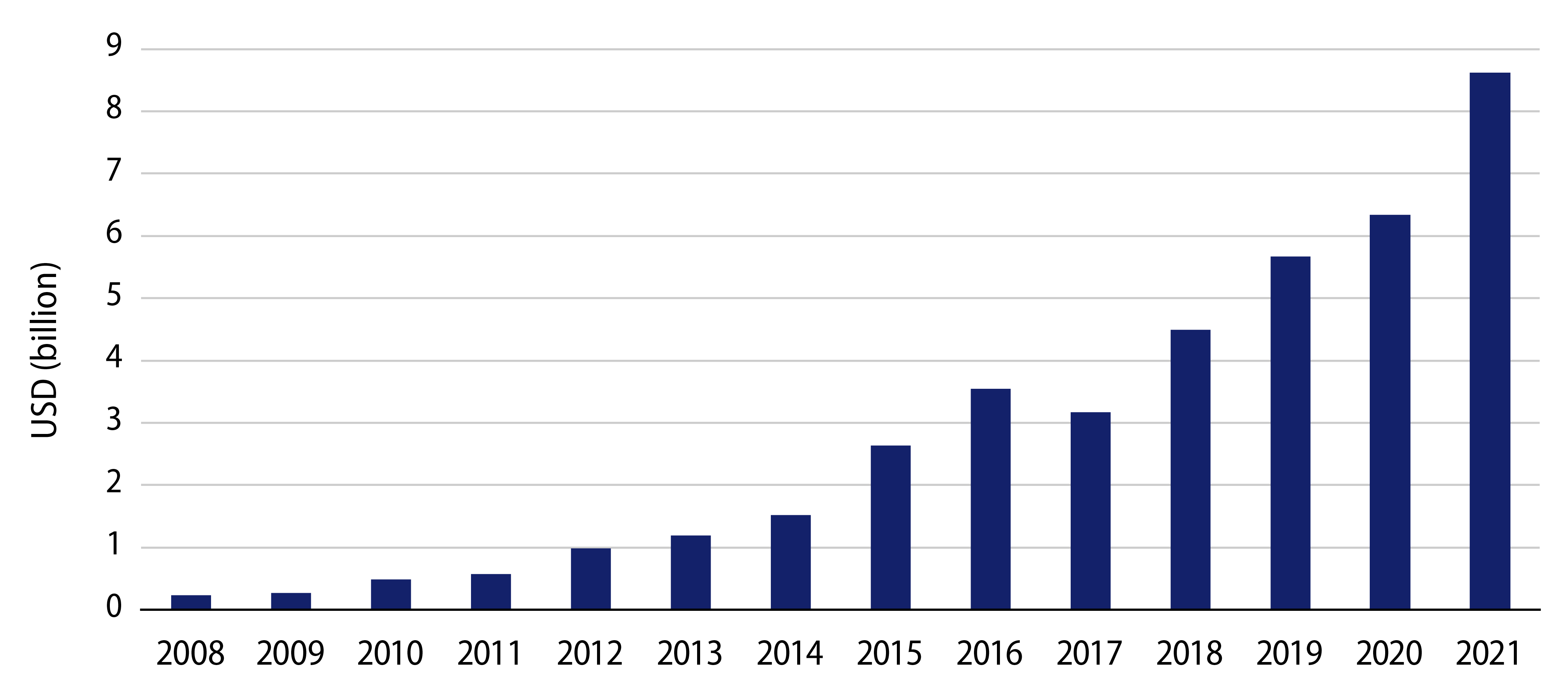

Over the longer term, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies will also benefit from foreign multinational corporations’ diversification efforts in their China+1 supply chain strategy and the significant rise in China overseas direct investments given geopolitical considerations and lower labour costs compared to the mainland. Of note, significant relocations have occurred from China to ASEAN in the electric vehicle supply chain.

US-China Geopolitics Risks and Taiwan

The strategic geopolitical friction between the US and China has extended from trade and technology to the military. Taiwan has become the geopolitical flashpoint of the ongoing power competition between the world’s two largest economies. Predicting geopolitical timelines and outcomes with any degree of accuracy is difficult in the best of times and nearly impossible when it involves two great powers, especially when the impact of such a confrontation would reverberate not just through the region but across the globe. That said, it is clear that further deterioration of the already frigid US-China relationship could result in significant adverse financial market reactions and dislocations.