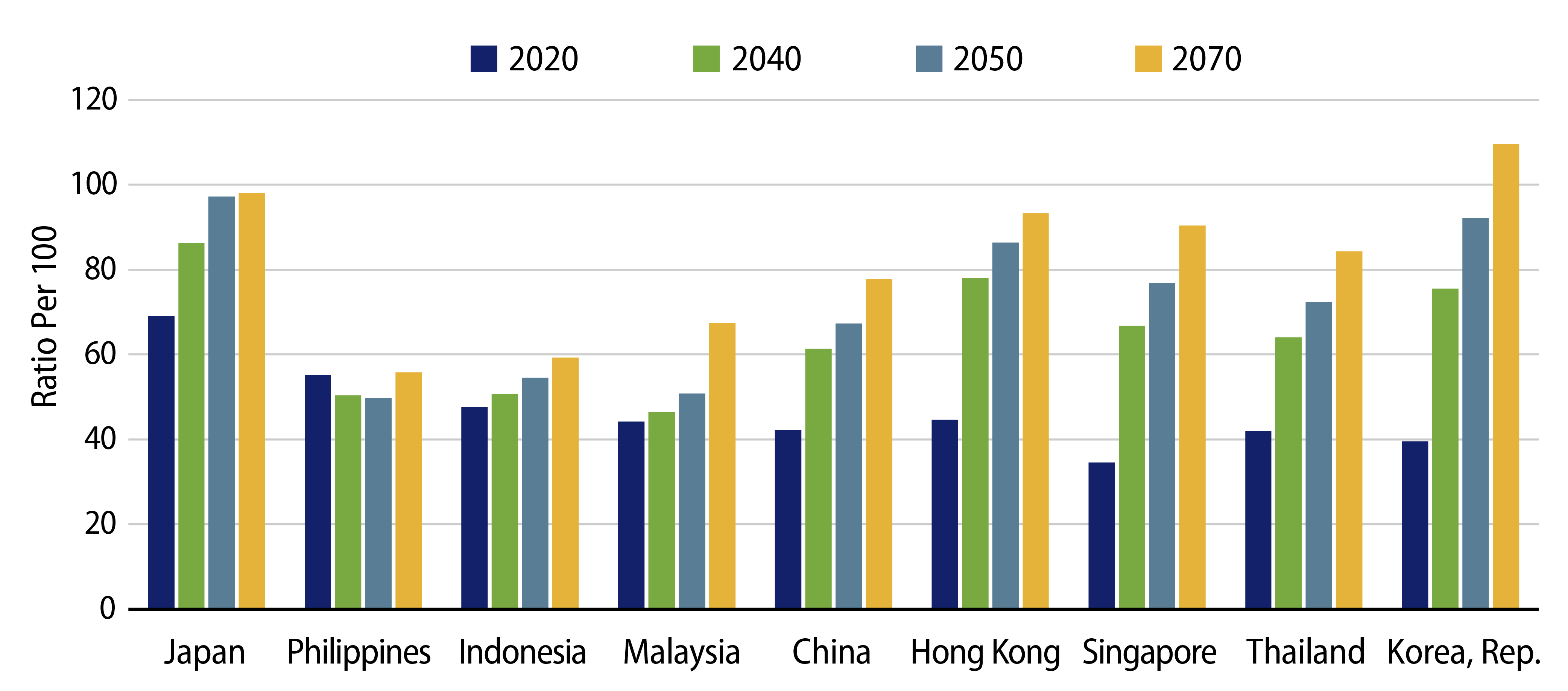

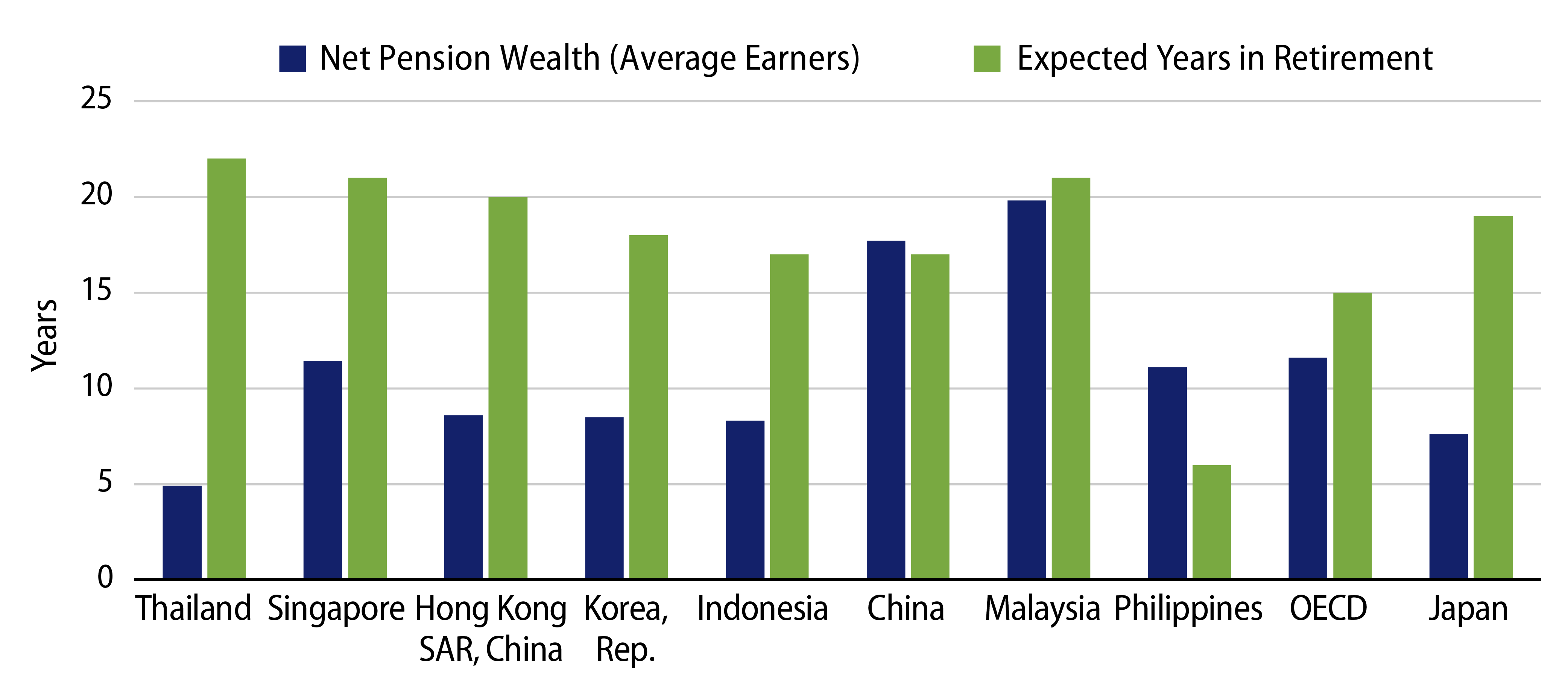

Dependency ratios have been increasing across developed Asia following the post-WWII baby boom. Following trends in developed Western economies, people in Asia are living longer and having fewer children in urban areas due to the higher cost of living and the personal/financial freedom tradeoffs associated with few or no children. Hence, the ratio of old dependent persons (> age 65) supported by working adults (roughly ages 25-64) has steadily climbed (Exhibit 1). The problem of ageing demographics is exacerbated by inadequate savings and pension replacement income. A recent study from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that the gap between the estimated years in retirement versus pension longevity expressed in years is exceptionally wide in a number of Asian economies (Exhibit 2).

Impact on Labor Cost and Consumption

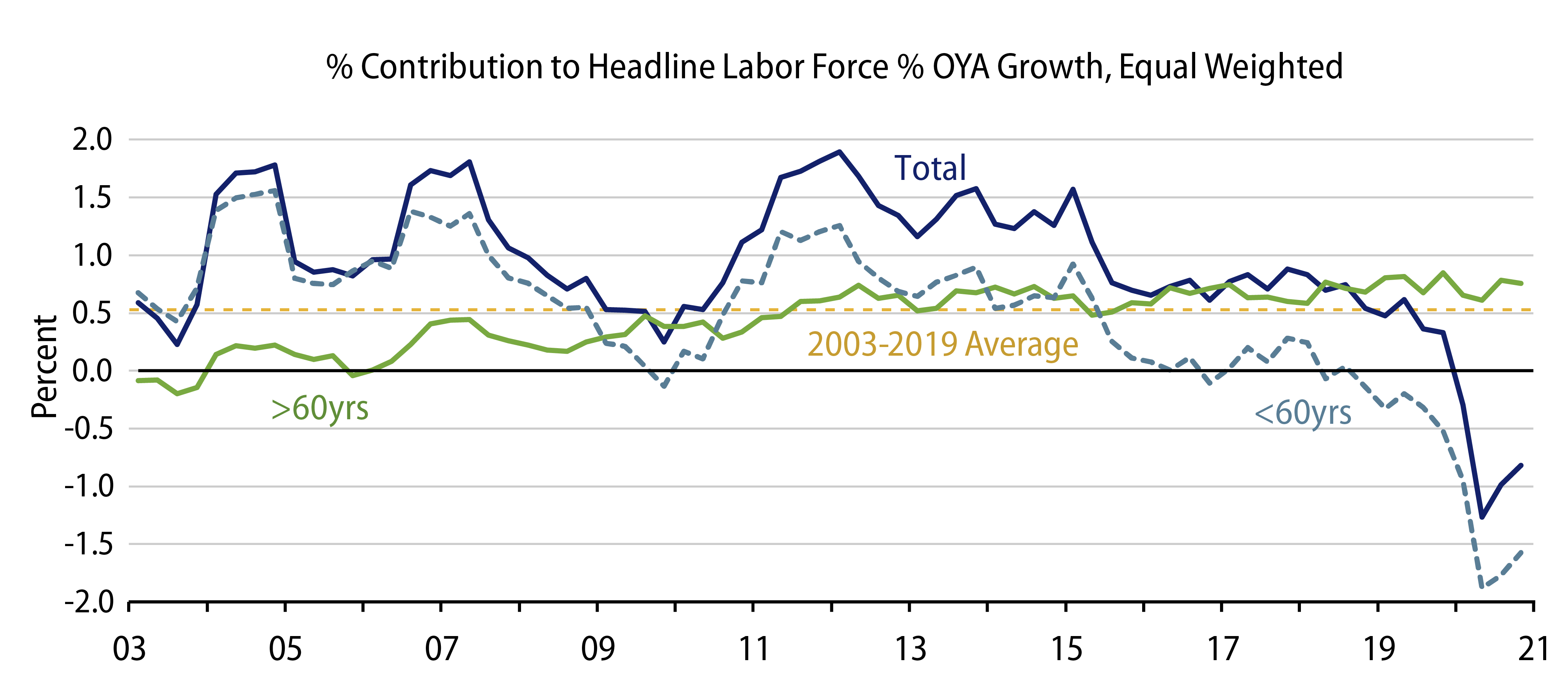

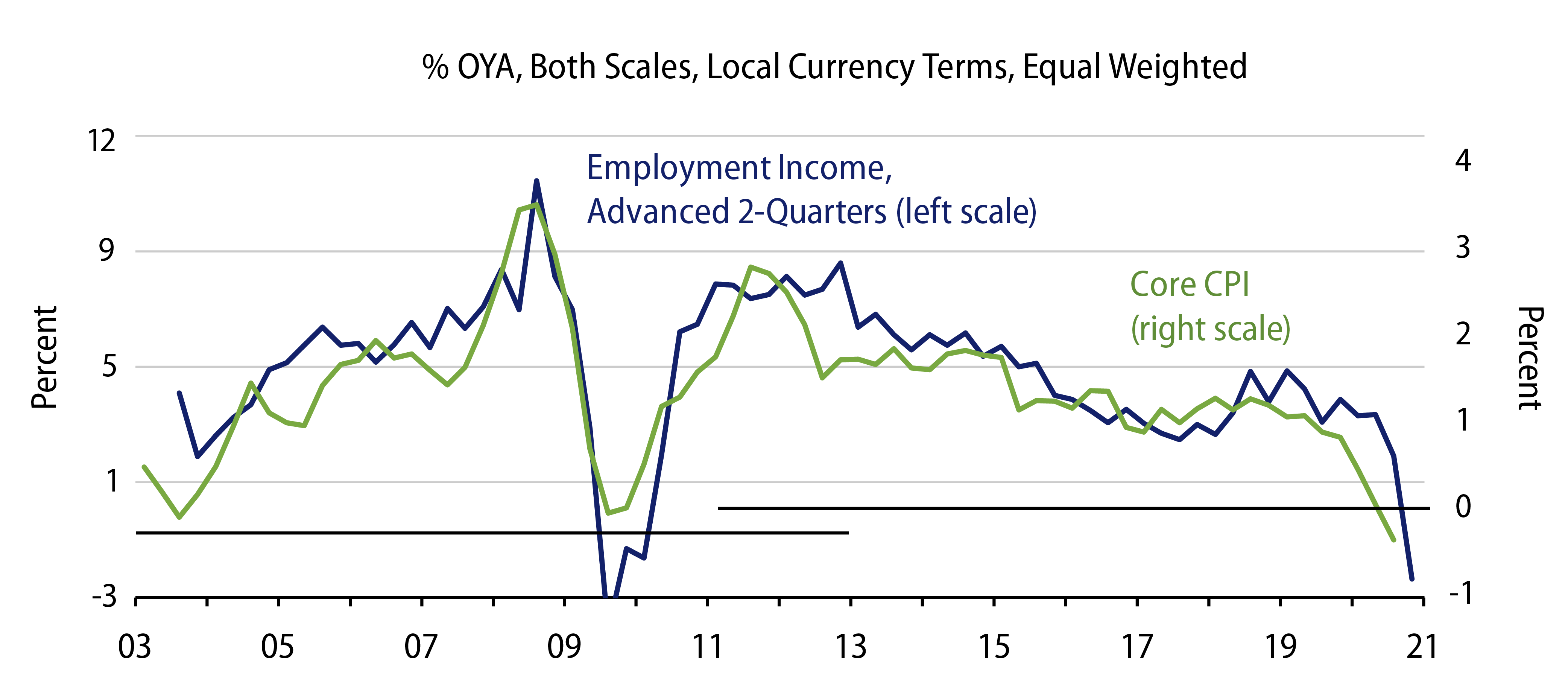

A consequence of ageing demographics compounded by pension inadequacy is that older people increasingly are being forced to return to the labor force to supplement their low pension/savings income (Exhibit 3). As this labor participation among older workers has risen out of economic necessity and their skills/productivity is not high in demand, older workers (e.g., in South Korea) take on the lower-paying jobs and boost the labor supply. With modest labor demand, higher participation of older workers could limit the upside for overall wages in the economy and fuel employment income disinflation (Exhibit 4).

The Japanese economy, which has the world's most advanced ageing demographics, has also showed that consumption and productivity can be structurally dampened with an increasing segment of older people who have weak/no income growth. This “Japanification” scenario results in a negative cycle whereby a rising number of older and low-income people with low purchasing power drives business to offer low price value products (e.g., JPY100 stores), thereby causing disinflation.

Ageing demographics also act in concert with secular disinflationary trends like the "Amazon effect" and the "gig economy,"and increasing automation further reduces overall price pressures from both a demand and supply perspective.

Implications for Asia Rates

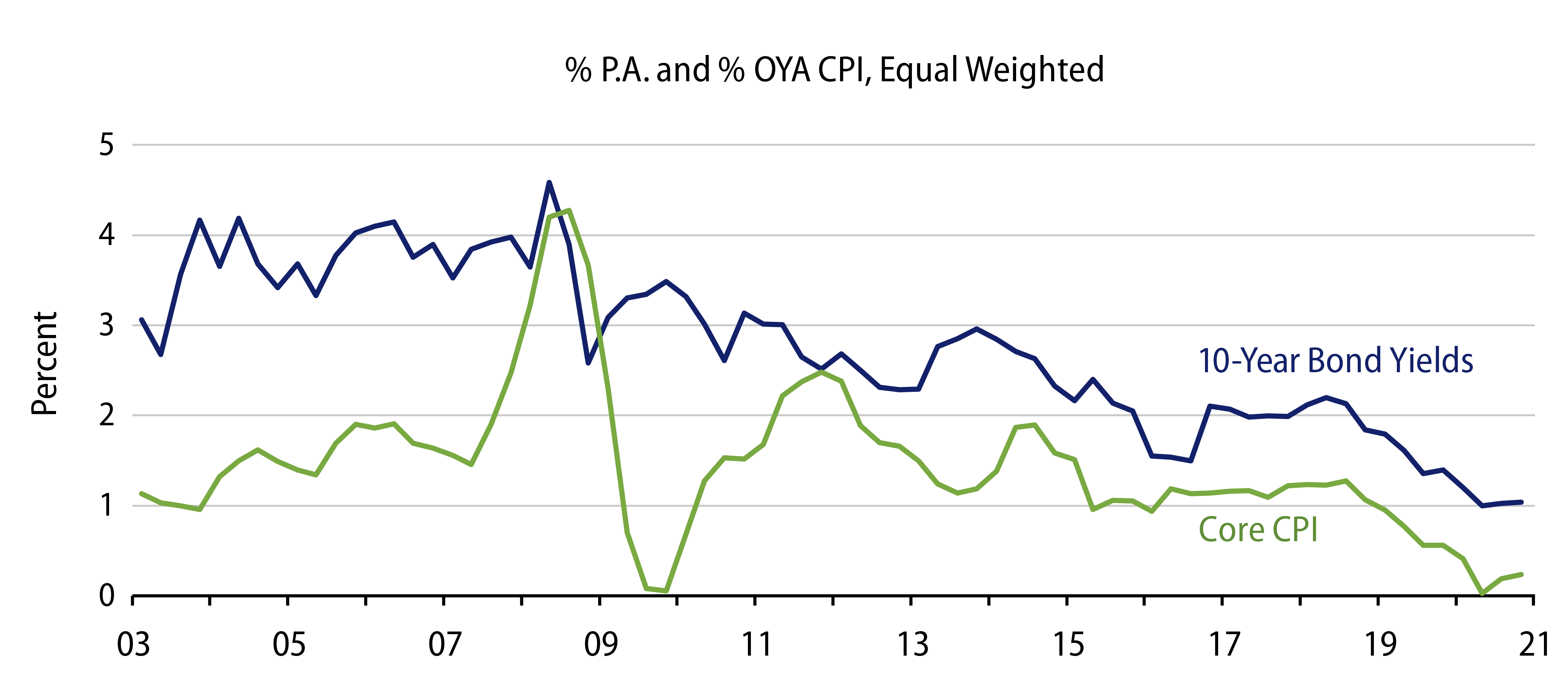

This impact of Asia's ageing demographics and inadequate pension/savings on labor costs and consumption has underpinned a benign secular inflation trend despite the occasional cyclical upturn (Exhibit 5). Together, these factors have created conditions for slow central bank moves, reflected also in the flattening of nominal term structures. Although real 10-year bond yields have been stable in the past five years, hovering around 1%, they have declined from 2% between 2003 and 1H08, as nominal yields continued easing, reflecting slowing core inflation (Exhibit 4).

Implications for Asia FX

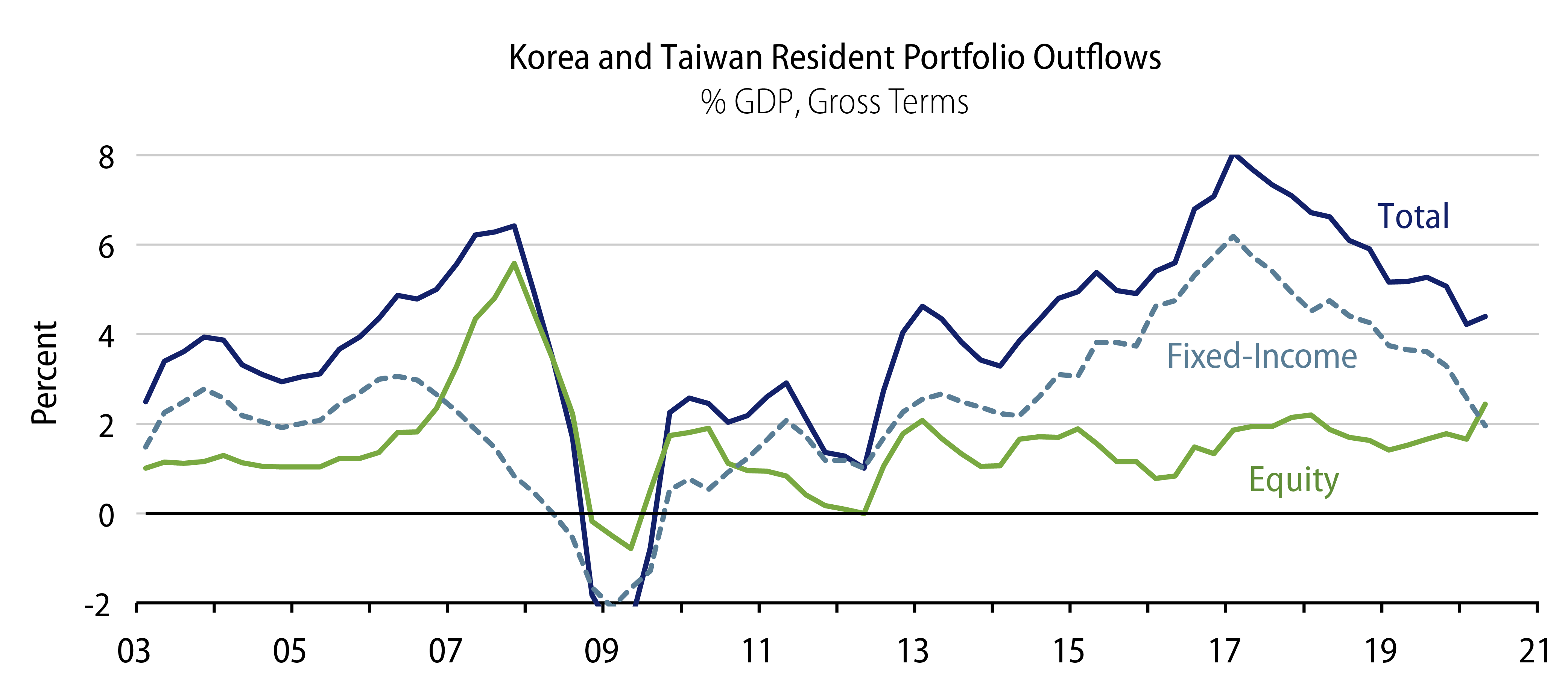

A protracted period of lower risk-free domestic yields in Asia likely will gradually change behavior among households and institutional investors, resulting in an increased allocation to overseas assets in search of higher returns (e.g., Taiwan and South Korea). These capital outflows from the high-savings economies would aid the recycling of current account surpluses, owing to weak domestic investment amid limited growth prospects. In a blue-sky scenario, this would prevent excessive Asia FX strength and result in higher long-term returns for pensioners.

The offshoring of domestic capital also looks to be on an uptrend. Two features of resident portfolio outflows in recent years are notable: the rise in outflows and the higher share of fixed-income flows relative to equities. However, recently equity outflows overtook fixed-income after global bond yields collapsed due to ultra-accommodative monetary policy in the US and the developed world (Exhibit 6). These observations are consistent with findings in other geographies as well (see the BIS working paper from Ammer, Claessens, Tabova, Wroblewski, "Searching for Yield Abroad: Risk-Taking Through Foreign Bond Investment in US Bonds").

Rising dependency ratios also add pressure on pension systems, with lackluster returns placing hard constraints on policymakers’ choices, be it reducing intergenerational transfers through raising retirement ages or reducing payouts or maintaining the status quo and leaving the future pension overhang for future policymakers to decide. Regardless, there are social and political facets of the economic outcomes of demographic trends and lower returns—and how these are dealt with, either via risk sharing or risk pooling, will likely have longer-term implications for fiscal positions as well.

Are Demographics Destiny?

Demographics-induced changes are often characterized as glacial-like tides for financial assets—very slow-moving, but in a direction of travel that is certain and entrenched. However, there are some path dependencies and inflection points that policymakers can influence to significantly defer or overcome the negative economic consequences of Asia’s ageing demographics trend.

First, raising the retirement age and implementing an anti-ageism culture in the workplace could result in older workers receiving a better income and raising their consumption. This economically sound solution, however, faces a number of obstacles as outlined in this example regarding South Korea (link shows a free article preview; full article available to paid subscribers). Indeed, policymakers need to factor in societal and cultural biases when crafting policies to raise retirement age.

A second strategy is to establish strong investment teams and pool various pension funds to achieve higher long-term investment returns with lower investment fees for pensioners. In this regard, the Singapore Investment Corporation, which was incepted in 1981 to help manage the nation’s Central Provident Funds, is a robust model for other Asia countries to emulate.

Third, it remains possible to slow down or negate ageing demographics headwinds via innovation and productivity growth. For example, recent figures showed that China’s population has grown at its slowest rate since the early 1960s and is ageing rapidly. However, the number of people with a university education almost doubled to 15.47 persons per 100 persons in the last decade and the average years of schooling for people aged 15+ increased from 9.08 to 9.91 years. Having a pool of well-educated STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) graduates has been shown to boost labor productivity, innovation and the number of well-paid jobs. This has been described as replacing the “population” with the “engineering” dividend. In the same vein, increasing robotic automation along with advances in artificial intelligence (AI) research and development investments can help to compensate/overcome the ageing demographics labor shortfalls.

Finally, ageing economies such as Singapore’s have augmented their labor pools with immigration and foreign white- and blue-collar laborers since the last decade. In many East Asia economies, this growing foreign-born labor force requires a major cultural and societal acceptance shift, which is gradually occurring. In mainland China, for example, rural urban migration via the Hukuo permit system is an internal migration lever to increase the mainly blue-collar workforce contribution in cities—and the urbanization ratio is now 63.9%, which is 14.2% higher than in 2010.