Executive Summary

- While the Fed is expected to hike rates twice more this year, the potential removal of the word “accommodative” from its guidance would be a more notable development.

- If policy is no longer “accommodative,” then the implication is that it must be approximately neutral. Although the Fed may not say that directly.

- Moving beyond neutral to restrictive policy will happen only if there is a strong justification in terms of imbalances or rising risks of imbalances.

- It’s not clear that such a move would be justified in the current environment. The Fed may instead choose to pause around neutral and wait for clearer evidence that it’s time to tighten.

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) responded to better than expected US growth by raising interest rates in June. The most recent economic data has generally maintained its firm tone. The FOMC will accordingly raise rates at the upcoming September meeting and potentially again in December, should the data hold. These two additional hikes are widely expected and won’t be especially newsworthy.

A more important development will be how the FOMC characterizes the stance of policy after these rate hikes. There is a good chance that the description of policy as “accommodative” will be dropped from the post-meeting statement following either of the next two hikes. The implications of such a change, if it does occur, would be significant. It would signal that the rate hiking cycle has entered a new phase, and would thereby call into question the extent of future rate hikes. It’s not clear whether the consensus is ready for such a change. It’s common to hear market participants refer to the Federal Reserve (Fed) as being on auto-pilot. By dropping the characterization of policy as “accommodative,” the FOMC would be casting serious doubt on such views.

Removing Accommodation: The Hiking Cycle Thus Far

The FOMC’s characterization of policy as “accommodative” has been a constant feature of the current hiking cycle. In the December 2015 press conference, when the FOMC raised rates for the first time in nearly a decade, then-Fed Chair Janet Yellen justified the move by saying:

Fed Chair Jay Powell has continued the practice. In the March 2018 press conference, Powell’s first press conference as chair, he said:

There is more than simply messaging at work here. The FOMC’s justification for raising rates has generally been that accommodative policy is no longer needed. This is a relatively straightforward argument, as both inflation and unemployment are near targeted levels. This line of argument does not, however, justify moving to restrictive policy. To justify restrictive policy, the FOMC must make the case that there is an imbalance, or at least a significant risk of one, that would be addressed by slower economic activity. The final section of this note addresses whether or not such a case can be made today. For the moment, note that the characterization of policy as “accommodative” is part and parcel with the hiking cycle to date. Once policy is no longer deemed to be accommodative, a different set of arguments must be made to justify further hikes, and the policy discussion will take on a very different character, accordingly.

A Step Back From Forward Guidance?

If policy is no longer “accommodative,” then the implication is that policy must be approximately neutral. But the FOMC may stop short of stating that directly. Stepping back from categorizing policy one way or another would be consistent with Chair Powell’s broader approach.

In his Jackson Hole keynote address last month, Powell eschewed overreliance on economic models, and in particular on estimates of unobservable concepts such as the natural rate of unemployment or the level of neutral policy. Such estimates are, according to Powell, “imprecise and subject to further revision.” Powell went so far as to blame the Great Inflation of the 1970s on these economic models, saying that a “key mistake was [that] monetary policymakers placed too much emphasis on imprecise…estimates of the natural rate of unemployment.” Powell is determined not to repeat that particular mistake, especially with regard to the unemployment rate. He has been dismissive of fears that the unemployment rate is dangerously low, offering instead “no one really knows…we have to be learning as we go.”1 Assessments of policy as “accommodative” or “neutral” are likewise based on equally imprecise models, and by extension should also be treated with a healthy dose of skepticism. Dropping the characterization of policy from the post-meeting statement would be a natural step for Powell, as it would underscore the distance between the FOMC’s approach and one based on imprecise economic estimates.

The high level of uncertainty surrounding the level of neutral policy is reflected in the FOMC’s own publications and statements. In estimates presented at its June meeting, the range of FOMC members’ estimates for a long-run neutral policy rate ran from 2.25% to 3.50%. FOMC members have stated a range of views in public as well. On the lower end of this range, New York Fed President John Williams has said neutral policy is “probably around 2.5 percent”2, and (recently confirmed) Vice President Richard Clarida has said neutral policy is “closer to 2 percent than to 3 percent”.3 Those on the higher end of the range include regional presidents Loretta Mester, Robert Kaplan, and Eric Rosengren. Importantly, Powell has been non-committal about his own view on the level of neutral policy. Perhaps he is sufficiently skeptical about the precision of these estimates that he has resisted giving just one number, and would instead be more comfortable with a range.

Should the FOMC increase rates in September and then again in December, the top of the fed funds range would rise to 2.25% and then to 2.50%, respectively. This would put the fed funds rate around the FOMC’s own estimates of the neutral rate. A more model-dependent FOMC may opt to start characterizing policy as “neutral” once that happens. Powell’s FOMC is unlikely to take that step, however, if for no other reason than it is uncertain. Nonetheless, dropping the “accommodative” label would go in the same direction. For the purposes of anticipating future policy, the signal would be clear: policy that is no longer accommodative must be approximately neutral, and the process of “scaling back accommodation” would be over.

Hiking Past Neutral Is Possible, But Rare and Harder to Justify

Once policy has reached its approximately neutral level, the FOMC must consider a different set of arguments in deciding whether or not to pursue additional hikes. It will no longer be sufficient to observe that inflation and unemployment are near target levels. Moving into restrictive territory is an assertive step—implicitly the FOMC will be aiming to slow economic activity through tight monetary policy—and such a deliberate step requires a justification. Given that the cost of slower economic activity is immediate and widely felt, the FOMC needs to have considerable confidence in its assessment in order to move forward. Absent that confidence, the FOMC may decide to refrain from taking such an assertive step.

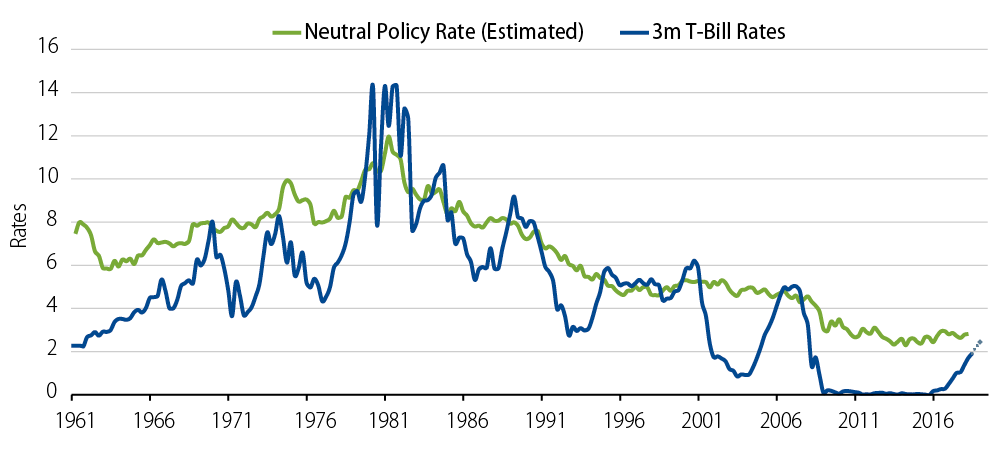

To be clear, this is not to say that the FOMC can’t ever decide to move to restrictive policy. Indeed, the FOMC has done exactly that a number of times in its 100+ year history. The chart below shows the level of nominal fed funds rate together along with an estimate of the neutral policy rate. (As emphasized above, the estimated level of neutral policy is imprecise and should be taken as indicative only.) Episodes of tightening past neutral are relatively rare, and when they do occur policy rates tend to exceed neutral by only a small amount. The obvious exception is in the 1970s when a confluence of factors made extraordinarily restrictive policy both justifiable and much needed.

In the other instances when policy was tightened past neutral, the FOMC was concerned about a building imbalance in the economy with regard to either inflation or financial stability. The inflation threat was perceived to come either from faster money supply growth (the late 1980s) or from accelerating economic activity (late 1990s). The financial stability threat was perceived to come from a combination of faster economic growth and over-extended credit creation (late 1990s and mid 2000s).

Neutral Policy Rates vs. 3-Month US Treasury Rates

An equally notable episode is one during which the FOMC showed restraint and chose not to hike past neutral. In 1995, following a considerable amount of hiking the prior year, then-Chair Alan Greenspan advocated a “wait-and-see” approach before taking policy into restrictive territory. Greenspan’s case for restraint was built on his sense that productivity had increased, which in turn muted the inflationary threat. Productivity is notoriously difficult to measure or model. As an alternative guide for policy, Greenspan advocated relying on the inflation data itself. In that instance, the inflation data failed to accelerate, not only validating Greenspan’s view but even allowing the FOMC to ease policy somewhat over the course of the year.

Interestingly, in his Jackson Hole speech Powell highlighted this episode in the mid-1990s as an example of especially successful monetary policy. Singling out this particular episode sends a few different messages. First, as the FOMC nears neutral policy, Powell is acknowledging that a successful strategy could be one of restraint, rather pushing past neutral into restrictive territory. Second, Greenspan’s emphasis on incoming data dovetails nicely with Powell’s skepticism about imprecise estimates from economic models. Finally, an especially important parallel between then and now is that inflation expectations were anchored, which lessened the pressure on the FOMC to tighten policy. Inflation expectations are still anchored today, suggesting that Powell may have a similar amount of flexibility.

The historical record on the FOMC moving past neutral makes clear that the Committee can do it. But such episodes are rare, and when they have happened the FOMC has had a clear sense of the building economic imbalance that warranted tighter policy. In no case was the tightening justified by observing that inflation and unemployment were near target levels. Tightening policy past neutral has real costs and cannot be taken lightly. Absent a strong argument on imbalances, Powell may prefer to follow Greenspan’s lead and let the data be the guide. Indeed, his Jackson Hole speech suggests his predisposition may be to lean that way.

What’s the Outlook After Reaching Neutral?

In the near term—specifically after the next hike or two—the FOMC may choose to stop characterizing policy as “accommodative.” While the Committee may also refrain from characterizing policy as neutral, the implication will be clear. From that point on, with the process of withdrawing accommodative policy now in the past, the FOMC will be surveilling the incoming evidence, on the lookout for imbalances that may warrant restrictive policy. At this stage, it’s far from obvious where it would find any.

The inflation rate has moved up toward the Fed’s 2% target, but has not shown any acceleration past it. The limited increase in inflation, even though growth has accelerated meaningfully, speaks to the magnitude and persistence of the long-term disinflationary pressures on the economy. On the financial stability side, there are the usual concerns about high prices of financial assets. High prices, however, are rarely a financial stability threat on their own. It is only when high prices are combined with excessive leverage that the risks increase. And the leverage in the economy has remained constrained, as private non-financial credit growth has actually lagged nominal GDP growth over the last five years or so.

The environment can, of course, change. Indeed the average hourly earnings print in the August employment report gave some indication that labor markets may finally be tightening. There are risks on the other side as well. The pressure on emerging market growth has raised concerns about global growth, which could in turn reverberate back to the US, as has been common in other periods of slower global growth. Either one of these could develop into something more. Until they do, however, the FOMC may choose to pause at neutral, preferring to wait and see.

Endnotes

- Chair Powell, FOMC Press Conference, June 13, 2018

- “Fed’s Williams Says Rates May Start to Brake Growth By Next Year,” Reuters, June 1, 2018 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-williams/feds-williams-says-rates-may-need-to-rise-above-neutral-next-year-idUSKCN1IX5T9

- “Clarida Is Fed Vice Chair Front-Runner, Source Says,” Bloomberg, March 1, 2018 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-01/clarida-is-said-to-be-considered-front-runner-for-fed-vice-chair

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/policy/rstar/overview