In our last report, Charting the Next Chapter in EM Central Bank Reserve Management, we observed that emerging market (EM) central banks have evolved significantly from the era when repeated financial crises fostered a deep conservatism in decision-making. That prudence was well founded, but the external environment these institutions face today is markedly different. Fragmented markets, technological innovation and shifting definitions of what constitutes a “safe asset” are reshaping the global reserve landscape. Within this context, a new generation of reserve managers is taking on leadership roles, tasked with maintaining the credibility and resilience built by their predecessors while guiding their institutions toward greater adaptability. The challenge is not replacing prudence with risk-taking but embedding innovation within prudent governance itself.

While research and surveys on reserve management are abundant, they often describe existing practices rather than offer actionable guidance for this new generation of practitioners.1 This is understandable: many smaller EM and frontier market central banks face constraints in capacity, investment expertise and governance—limitations that make one-size-fits-all recommendations difficult to apply in practice. Still, every problem has a solution, and reserve managers should remain open to working with external partners who can help them cut through the groupthink that often afflicts a close-knit policy community. The journey toward modernization does not need to be a lonely one; as other fields have shown, meaningful progress often begins with collaboration and small-scale experimentation.

A case study from another discipline illustrates this point. In the 1990s, doctors at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital faced a serious problem: frequent errors during the transfer of critically ill children from surgery to intensive care.2 After watching a Formula 1 race on television, two surgeons noticed how Ferrari’s pit crew performed dozens of complex tasks—changing tires, refueling and recalibrating equipment—in perfect coordination and in just a few seconds. Impressed by this precision under pressure, the doctors invited Ferrari engineers to observe their own process and later visited the team’s facilities in Italy to study how they worked. Together they redesigned the hospital’s handoff process, introducing clear roles, rehearsed steps, checklists and a single coordinator to oversee communication.

The partnership succeeded because it combined humility to learn from others with the discipline to test ideas in a controlled, measurable way. In reserve management, this same mindset—collaboration grounded in testing—can close the gap between tradition and innovation. Like the hospital team, reserve managers can benefit from looking beyond their own field, adapting proven methods from other areas to identify bottlenecks, streamline workflows and strengthen how complex systems function together.

Pilot testing, a structured process for trying new ideas in a controlled and measurable setting, offers a practical way to do this. The concept resembles the “digital-twin” frameworks used in aerospace, manufacturing and increasingly across financial institutions exploring artificial intelligence.3A digital twin replicates real-world operations in a virtual environment to allow testing of how systems respond before implementation. Likewise, in the context of reserve management, a pilot test allows reserve managers to evaluate new instruments or portfolio strategies within a clearly defined, risk-controlled framework.

External asset managers are natural partners for pilot testing because they already use similar processes to evaluate new capital-market instruments and portfolio concepts. In a highly competitive industry shaped by constant product innovation and shifting investor demand, product management teams work closely with investment, risk and operations groups to assess the viability of both existing offerings and new ideas. Once a promising approach is identified, it undergoes rigorous review across risk, legal, compliance and settlement teams before a product committee presents a proposal to senior management for seed capital. That capital funds a live incubation phase—essentially a pilot—where the concept is tested with real money, monitored closely then refined before being introduced to clients, consultants and the broader market.

While central banks are not driven by profit motives, they can adapt this framework to test the viability of new investment tools and asset classes. By dedicating a small and clearly defined share of reserves, they can build practical experience and generate real data without jeopardizing mandates. Pilot testing challenges assumptions, aligns teams and provides a factual basis for policy decisions, turning innovation into part of risk control rather than a threat to it. Because pilot portfolios use existing custodians, reporting tools and staff, they require few new resources yet deliver valuable insight into data accuracy, settlement efficiency and valuation integrity. The result is a sharper view of institutional readiness to evolve with that particular instrument or strategy.

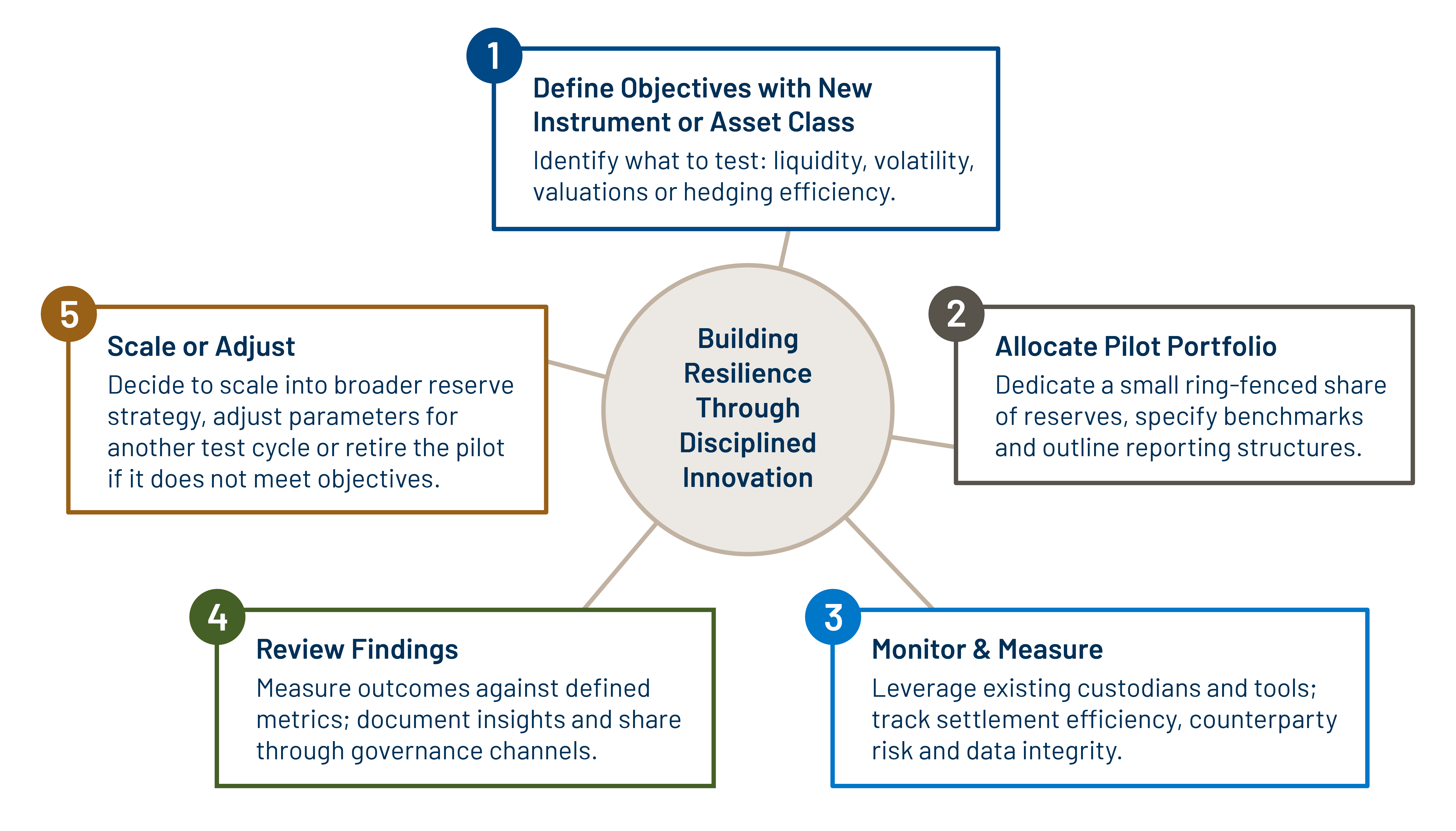

For reserve managers, a practical framework could be implemented in a few distinct steps. First, define the objective—testing liquidity, volatility behavior, valuation or hedging efficiency. Second, allocate a small portion of reserves, typically less than five percent, to a controlled portfolio with a defined benchmark and reporting structure. Third, monitor results over time, tracking price discovery, settlement timeliness, counterparty exposure and data consistency. Fourth, document findings and share them through internal reports or workshops. Finally, review outcomes to decide whether to scale, adjust or retire the pilot.

This disciplined approach converts experimentation into institutional learning. A pilot portfolio becomes a proof of concept that builds a verifiable record across a market cycle—evidence that strengthens strategy, governance and confidence among internal policymakers and oversight bodies.

Several central banks have already put this type of approach into practice across both financial and technological domains. The Reserve Bank of India piloted the tokenization of certificates of deposit through its wholesale digital-currency platform to evaluate settlement efficiency before broader rollout4, while the US Federal Reserve used its 2023 Climate Scenario Analysis to test new frameworks for assessing risk exposure under hypothetical stress events.5 Norges Bank’s investment arm has taken a similar approach, developing an AI-powered engine to monitor portfolio managers’ decision-making patterns and identify behavioral biases, improving execution quality and reducing costs.6 At the same time, the People’s Bank of China’s e-CNY trials, along with the regional mBridge project, developed by the BIS Innovation Hub in collaboration with the central banks of China, Hong Kong, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates, illustrate how disciplined experimentation can enhance cross-border payments by enabling instant, low-cost and secure settlements while managing technological and reputational risks and deepening institutional learning.7 Together, these initiatives show how structured pilot testing, whether in EM or advanced economies, builds institutional confidence, strengthens operational readiness and fosters a culture of continuous learning. The same mindset should guide reserve management: testing, refining and validating practices that strengthen prudence rather than erode it.

Well-executed pilots serve an important purpose: they demonstrate competence. Clear objectives, transparent metrics and consistent reporting foster organizational confidence that change is managed thoughtfully and proactively rather than reactively. When results are presented through established governance channels, they reinforce the credibility of the process rather than challenge it. In this way, pilot testing becomes a natural extension of prudence, allowing institutions to evolve while remaining anchored to their mandates of safety, liquidity and trust.

Ultimately, timing matters. For reserve managers—and especially for the next generation of central bankers who have not lived through the crises that shaped the views of their predecessors—the best moment to modernize comes during periods of calm, not crisis. Stability offers the bandwidth to test, measure and refine processes, while waiting for volatility to return only reinforces structural rigidities and limits the ability to adapt when it matters most. If modernization is deferred until the next market shock, central banks risk being constrained by outdated frameworks and fragmented systems. The response, however well intentioned, may fall short, especially in the eyes of the people and institutions they are mandated to protect. Taking initiative now, while conditions allow, is not optional. It is the difference between reacting to change and driving it.

ENDNOTES

1. 'World Bank, 2023, Reserve Management Survey Report 2023, Insights into Public Asset Management, RAMP Survey No. 4

2. Baker, Caroline, 5 May 2023, “The Doctors Who Sought Advice from Formula One”

3. MIT, 23 December 2024, “Digital Twins and the Future of Learning”; McKinsey, 26 August 2024, “What Is Digital Twin Technology?”

4. Reuters, 11 October 2025, “Indian central bank to launch pilot for certificates of deposit tokenisation, official says”

5. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 29 September 2022, “Federal Reserve Board announces that six of the nation’s largest banks will participate in a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise designed to enhance the ability of supervisors and firms to measure and manage climate-related financial risks”

6. Investment Magazine, 26 June 2025, “How Norwegian giant NBIM spots portfolio managers’ biases using AI”

7. Forbes, 6 March 2025, “A 2025 Overview Of The E-CNY, China’s Digital Yuan”; BIS, 26 October 2022, “Project mBridge: connecting economies through CBDC”