Trade Wars in the 21st Century: Perspectives From the Frontline

War is delightful to those who have no experience with it. ~Erasmus

Executive Summary

- Trade tensions or a full-scale trade war would have major investment implications.

- Western Asset’s global investment team is closely monitoring the situation from the frontline of the looming trade war.

- We examine the three major trading relationships subject to disruption: US-China, NAFTA and Europe.

- Our initial bottom-up assessment across key investment sectors provides insight into the potential trade vulnerabilities.

- We also explore the implications for autos, commodities and financials, the three most prominent goods and services likely to be affected by trade strife.

Market participants are increasingly concerned that the Trump Administration’s ongoing tariff crusade against China and other global trading heavyweights might be the tinder that could ignite a full-blown trade war. While such a risk should not be underestimated, we are cautious about leaping to any conclusions as the situation remains highly fluid and unpredictable. Because the global economy and industry supply chains are much more integrated and complex today than they were during the last global trade war, it is much more challenging to identify, let alone quantify, the first- and second-order effects of a potential trade war. In this note, we first provide our top-down assessment of current events followed by our bottom-up views from Western Asset’s global sector teams. We believe a perspective from the “frontline” of the looming trade war is invaluable to help frame the risks associated with this rapidly developing situation.

Using History as a Guide

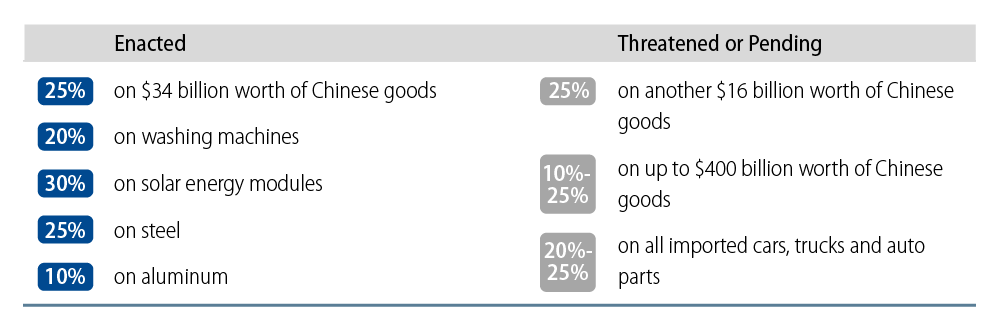

Increasing protectionist rhetoric emanating from the major economies has led market participants to look for parallels with the last global trade war as a guide for what one may expect to happen next. In 1930, against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the US Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act which imposed steep, sweeping tariffs on roughly 20,000 imports. Its intent was to reduce the foreign competition faced by US producers. However, its passage unleashed a wave of nationalism across the entire world, followed by a wave of trade reprisals from Europe and Canada that ultimately exacerbated the US Depression and crippled global trade over the next five years. The key lesson from this period is that trade wars are not “easy to win,” and it takes an inordinate amount of time to reverse their pernicious effects. While we are hopefully far from seeing a repeat of that history today, markets have clearly been unsettled over the past few months by the pace of escalation and impending tariff implementation deadlines (Exhibit 1).

Trump’s Trade War – Tariffs Enacted or Threatened

The Trump Administration’s strategy to protect US steel and aluminum industries and to counter Chinese high-technology policies has already provoked the threat of retaliation by America’s largest trading partners: China, Canada, the EU and Mexico. While retaliatory measures against the US have thus far been fairly limited, the risk of a major escalation continues to grow. In fact, it is already far from obvious how China or the US can de-escalate tensions at this point.

The purpose of this note is not to forecast how the sequence of events surrounding a trade war might evolve. Rather, the intent is to discuss the potential impact(s) of a full-blown trade war, specifically with respect to areas that we believe are most relevant to fixed-income investors. In the following pages, we provide our thoughts on how a trade war might impact our current views on the global economy, the US economy and other economies as well as major industries worldwide.

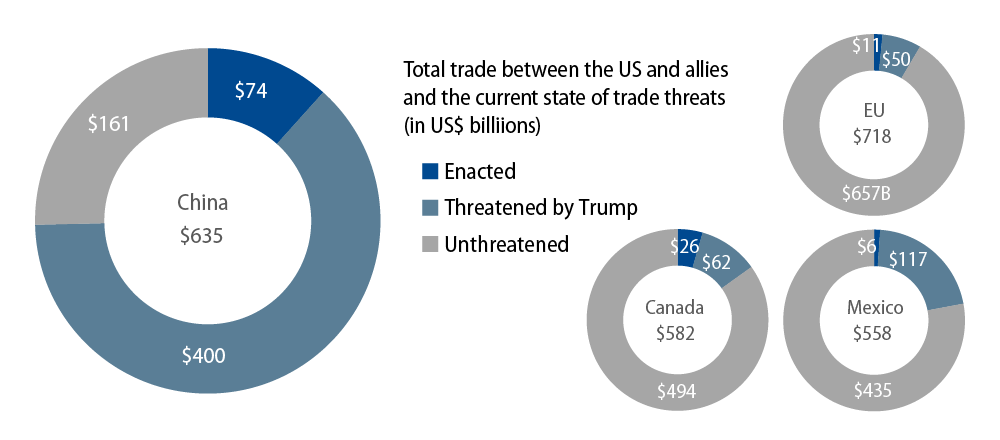

The Three Primary Trade Relationships Subject to Disruption

The escalation in trade tensions is a clear risk to Western Asset’s global outlook. The IMF, in its latest G-20 Surveillance note, was unequivocal in its view that “the likelihood of escalating and sustained trade actions has risen, threatening a serious adverse impact on global growth.” In a worst-case scenario, which assumes a series of escalating tariffs and a global shock to confidence, global GDP would be expected to fall 0.5% by 2020, with differing levels of impact across countries and regions.1 We take particular interest in the IMF’s assessment that the US is deemed to be “especially vulnerable” as the “focus of retaliation.”

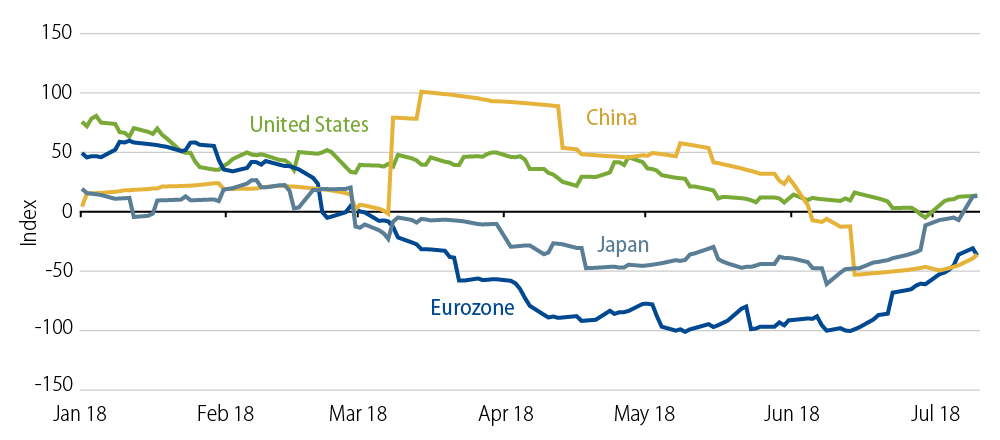

For now, we remain cautiously optimistic on global growth prospects. Based on the macro assessments from our investment teams worldwide, we expect the divergence between US growth and the rest of the world will abate as we move into the second half of 2018. Looking at the Citi Economic Surprise Index, which measures how economic data are coming in relative to expectations, the US appears to be stabilizing while the drop in the eurozone through June has been the most striking (Exhibit 2). More recently, however, growth in Europe and China has improved and we expect this to continue.

Citi Economic Surprise Index

Any major disruptions that destabilize these relationships would likely have a lasting and negative impact on the global economic outlook. With this in mind, we provide our thoughts on the three primary areas of focus dominating the discussion of a trade war with the US, China, North America and Europe.

US-China

A breakdown in the US-China relationship would have major reverberations throughout the world, given the overall size and complexity of the trading relationship and the number of countries that are heavily integrated into the supply chain. At the center of the bilateral conflict is the sizable US trade deficit against China, particularly in the area of computers and electronics (Exhibit 3). This has already triggered a Section 301 investigation to determine whether China is harming US intellectual property rights, innovation or technology development.2 More recently, the Trump Administration has not only threatened to impose tariffs on the bulk of China exports to the US, but also threatened to tighten Chinese investments in the United States and limit visas for Chinese citizens.

Key US Trading Relationships

We believe market concerns around these headlines may be running ahead of actual developments. Note that the tariffs on Chinese goods have not yet been implemented, and they are subject to a lengthy review period, during which their size and details can change. In fact, the scope of the aluminum and steel tariffs decreased substantially during the period between announcement and implementation.

Nonetheless, markets understandably remain unnerved over China’s potential retaliatory measures, both in terms of timing and the weapon of choice. One area that has generated significant client inquiry is whether a trade war will inevitably lead to China selling US Treasuries (USTs). While the possibility cannot be entirely ruled out, we think the chances of any meaningful UST sales are unlikely for two reasons.

First, China has more attractive retaliatory tools at its disposal. Thus far, it has announced a specific list of goods that would be subjected to counter-tariffs, choosing goods that have some political importance (e.g., agricultural exports) and calibrating the amount to be exactly equal to the amount of US tariffs that these counter-tariffs are responding to. By focusing on these characteristics, China appears to be maximizing its bargaining position, while minimizing the domestic economic impact.

Second, China holds USTs because it is in its self-interest to do so. China accumulated US dollar assets during the 2000s to prevent its currency from appreciating too quickly. Its current UST holdings are simply an artifact of the previous decision to hold USD-denominated assets, with USTs a relatively low-risk way to do that. If China were to sell USTs today, presumably it would also be simultaneously selling US dollar assets. China’s currency would likely appreciate as a result which is not in China’s interest, especially if it occurred as tariffs made China’s exports less attractive.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

Looking at another key hotspot, talks to renegotiate NAFTA with Canada and Mexico stalled earlier this year with both governments stating that they are prepared to strike back quickly and decisively against any US tariffs. Canada has already made such a move by imposing tariffs on approximately $13 billion of US goods in response to the steel and aluminum tariffs.

As context, the US administration has focused on trade deficit reduction as the key objective of any NAFTA renegotiation. Given that the US runs a small trade surplus with Canada, deficit reduction is squarely an issue that relates to Mexico. For progress on NAFTA to occur, the US would need to soften its stance on contentious issues including dispute settlement mechanisms, the sunset clause and auto rules of origin. This is unlikely to happen prior to the US midterm elections in November 2018. Adding to the uncertainty is that Mexico’s newly elected president does not take office until December 2018.

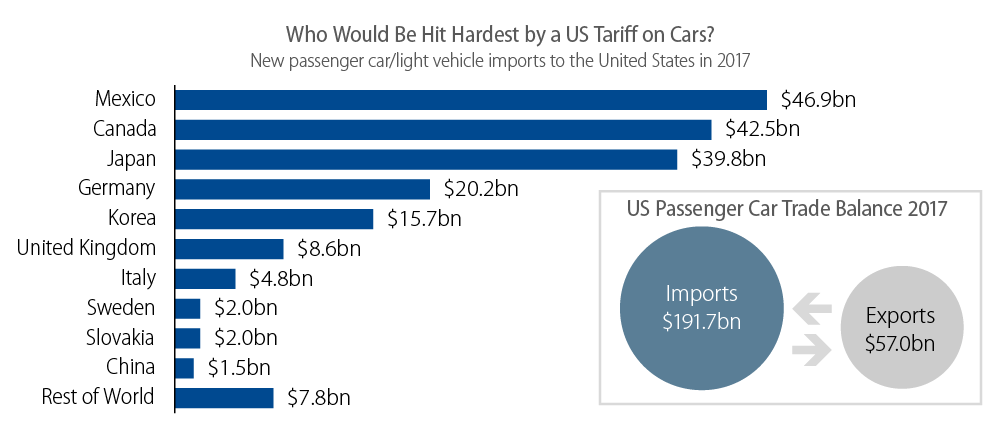

For these reasons, we expect the NAFTA negotiation timeline to extend into 2019. During this period, there is a lingering risk that the US may attempt to pull out from the current deal in an effort to negotiate two bilateral deals instead. We believe this outcome would: a) disrupt regional trade flows among the three countries, b) dampen foreign direct investment prospects for Mexico and c) negatively impact critical sectors in Mexico such as auto manufacturing (Exhibit 4).

Countries Impacted Most by US Tariff on Autos

Europe

The final hotspot to highlight is Europe. The Trump Administration initially threatened to apply a 25% tariff on auto imports, prompting the EU to respond that it would impose a reciprocal tariff targeting states sensitive to President Trump’s political base. As of July, discussions between both parties represent a welcome break in the escalating rhetoric, but we would emphasize that no formal action was agreed to and, admittedly, the devil is always in the details. Should Section 232 investigations—intended to determine the effect of imports on US national security—continue to result in an extreme scenario of higher auto tariffs against Europe, the direct consequences of a trade war on European growth would not be negligible.

Barring such an outcome, we expect European growth to move higher on the back of improved domestic consumption and investment as opposed to net exports which was the case in the second half of 2017. So far, the improvement in the Citi Surprise Index, other high frequency data and recent European Central Bank statements give us confidence around this view.

Western Asset’s US Growth and Inflation Outlook Is Intact (For Now)

Our fundamental view on the US economy remains intact. Recent changes to US fiscal policy are a tailwind for the near-term growth outlook, but are unlikely to materially improve the longer-term growth trajectory. We also believe this economic cycle will extend much further before we experience meaningful inflationary pressures. This is because the magnitude of growth created in the last nine years has been very low relative to what has been experienced in previous recoveries. Absent an acceleration in nominal GDP, we view the expected uptick in inflation this year as merely a move back to more normal levels while the economy heals.

It’s worth noting that many investors assume a trade war will lead to higher inflation. This is a common misconception based on what appears to be an obvious link—tariffs will raise prices and higher prices mean higher inflation. In a recent paper from Portfolio Manager John Bellows, Dispelling Two Common Misconceptions About Trade Wars, we asserted that while it is true that tariffs are likely to initially raise prices, as some of the cost of the tariff is borne by the importer’s margins, the increase in prices is a one-time event that fairly quickly runs its course. In contrast, when investors discuss “inflation” they are typically referring to an ongoing process with prices expected to rise month after month and year after year.

We think the more important point to underscore is the negative impact tariffs would have on aggregate demand and US growth over the longer term. For example, the imposition of the Smoot-Hawley tariffs coincided with the onset of the Great Depression and the worst deflationary period of the last 100 years. One-off inflationary effects of a single tariff imposition can morph into a deflationary spiral when trade conflicts become more widespread and set off a chain of retaliation and counter-retaliation measures.

This point was not lost on Federal Reserve officials as noted in their latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting minutes which stated, “that uncertainty and risks associated with trade policy had intensified and were concerned that such uncertainty and risks eventually could have negative effects on business sentiment and investment spending.” Our US credit team is closely monitoring on-the-ground activity in their respective industries. Thus far, they have not observed any marked pullback on business sentiment and capital spending which helps support our forecast of 2.25-2.50% growth in the US for 2018.

Fundamental Analysis Is Key to Identifying Vulnerabilities From Trade War Effects

The untested nature of a trade war across today’s sophisticated supply chains, formed through decades of globalization, and the unpredictability of the latest news renders futile any attempts at quantifying industry-level impacts with any precision. In our view, fundamental credit analysis remains the most effective tool to identify key vulnerabilities across global industries and companies.

As can be expected, the impact of a trade war would have implications across all credit sectors and valuations, but the degree of a sector’s vulnerability will depend on industry- and company-specific forces. In general, with the exception of those sectors that have been specifically targeted, direct or first-order impacts appear to be limited. Indirect or second-order effects for each sector are much more difficult to predict as they will be influenced primarily by macroeconomic effects and how corporate management teams, financial centers, global central banks and financial markets react.

Exhibit 5 highlights our broad assessment of trade war vulnerability by specific sector. We believe this bottom-up perspective from our research and investment associates on the “frontline” of the looming trade war offers investors a valuable tool for framing risks around a rapidly developing situation. We also provide a more detailed overview of our latest views and positioning on the three key sectors that have, thus far, generated a significant amount of client inquiry: autos, commodities and financials.

Summary of Trade War Impact Across Global Credit Sectors

Autos: A Key Sector in the Trump Administration’s Crosshairs

Simply put, tariffs of any meaningful size or consequence would result in a significant indirect tax on consumers. This has the potential to upend auto sales by reducing overall demand, raising unemployment rates in the sector (as a result of lower production rates), and threatening future investment in advanced engine technologies (hybrid/electric) and autonomous capabilities.

In the US, there are 14 domestic and international auto manufacturers which support more than seven million workers, invest more than $20 billion in research and development, and contribute approximately $200 billion in federal and state taxes. The benefits of tariff implementation for US-based original equipment manufacturers would be more than offset by the higher input costs and corresponding margin pressure associated with the proposed steel and aluminum tariffs for the auto industry.

As noted earlier, the impact of a full-blown trade war on the European auto industry would be debilitating. Discussions are underway at the German/EU level to propose that the US and EU look into mutual tariff reduction rather than an increase. However, this outcome remains far from certain. Brexit negotiations also represent another source of uncertainty to the region as a “hard” or “no-deal” outcome would severely disrupt the auto supply chain going across the Channel.

Given this context, we prefer investing in auto-related companies with strong balance sheets and large liquidity buffers that can help withstand near-term uncertainties, and companies with flexible operating structures that provide the ability to reduce costs and furlough employees quickly if trade wobbles make it necessary.

Commodities: Fundamentally Resilient but Vulnerable to a Global Downshift

In the near term, the damage sustained from a trade war on the energy sector, specifically oil, should be relatively contained. The historic price rout observed in 2015 focused the industry on repairing its balance sheet and building liquidity. That stated, a protracted trade war would be negative for the sector as a slowdown in global GDP would reduce demand for oil and destabilize the current, healthy supply-demand balance. With this backdrop, our attention is on upstream exploration and energy production companies and the less commodity-sensitive midstream operators.

With regard to the metals and mining sector, US policy toward China thus far has focused upon the steel and aluminum industries. The resulting higher prices have benefited domestic US steel and aluminum producers and incentivized increased domestic US production. However, over the short term, domestic steel and aluminum supply is unlikely able to respond quickly (i.e., restart) and downstream consumers may very well bear the brunt of higher prices introducing cost inflation that could potentially be passed through the supply chain. Many questions still remain such as the length of time that tariffs will remain in place, if exemptions are granted, and if China’s supply-side reform policies (e.g., shutting capacity for environmental considerations) remain intact.

Looking at the rest of the metals complex, the first-order impact of tariffs is muted. However, as trade war rhetoric intensifies focus has turned to second-order impacts and the potential for the sector to be adversely impacted by a slowdown in manufacturing activity. This has been observed in lower copper prices which have demonstrated a high correlation with the Chinese yuan. Consistent with the energy sector, metals producers have focused on balance sheet repair and liquidity preservation over production growth by curtailing capital investment. This positions the sector better in the event of a downturn.

Given these concerns, we prefer companies that continue to focus on profitable growth and capital discipline and that have an eye toward further improving their balance sheet.

Global Financials: Sufficient Armor to Weather Near-Term Challenges

In our view, the biggest potential impact on banks’ credit fundamentals from a global trade war comes from potential second-order effects. These include weaker economic growth or persistent lower rates that could lead to weaker credit quality and weaker earnings growth.

Looking at recent earnings reports from US banks, we see continued financial strength with no major institutions seeing any meaningful impact from trade friction. US banks typically generate most of their revenue domestically. For instance, US bank revenues range from 48% at Citigroup to 78% at J.P.Morgan, 86% at Bank of America and 96% at Wells Fargo. The obvious indirect negative impact would be a US growth slowdown that would lower earnings (both higher problem loans and lower loan growth).

Turning to the universe of major European banks, only a fraction have meaningful operations (in terms of revenues and assets) outside their respective home markets or the EU. Of these, most revenue collected from activities that are potentially sensitive to disruption in the international business order are fees (from wealth management or investment banking activities) rather than revenues from lending operations (which carry much more credit risk).

Unlike the US banks, a number of banking systems in Europe (especially in the periphery) are still in the process of improving asset quality and building capital. These would be the most vulnerable to a deterioration in economic sentiment and fundamentals in Europe or their domestic markets. Given that, the European banking system today is in a much stronger position fundamentally than at any time in the last decade. Since the crisis, European banks have built more than €700 billion in capital, nearly quadrupled their CET1 ratios (to 14.2% at the end of 1Q18) and reduced their NPL ratios to 3.9% from a peak of around 7% in 2015.

With these points in mind, our strategy emphasizes a quality bias to select banks with low risk business models in strong countries with healthy banking systems.

Staying on Offense

As is always the case with markets, the risks are two-sided. Given the intense focus on trade tensions recently, market prices may already reflect some of the downside risks. It could very well be the case that we have now seen the worst of the trade tensions, and that what has been announced thus far proves to be manageable for the US and the global economy. The news on trade could even improve from here, either due to a negotiated détente or possibly some kind of agreement in other trade areas. Any such positive development would presumably provide some support for spread sectors.

However, one can’t ignore the possibility that trade tensions may worsen. If tensions were to continue to escalate, it is not unreasonable to expect further pressure on spread sectors. This risk case underscores the need for diversified portfolios. As our Chief Investment Officer Ken Leech has argued over the past few years, USTs remain the best diversifying hedge in a broad fixed-income portfolio, and this is especially applicable in the event of a trade war.

From a spread sector standpoint, positioning our portfolios against such a risk is driven very much by individual issuer views which we have outlined in this note. We would argue that the better diversified a company is geographically and by segment, the more scope it has to address trade threats and weather the storm. All else being equal, it will be the larger companies that outperform in such an environment.

Endnotes

- GDP impact: US (-0.8%); Emerging Asia (-0.7%); Latin America and Japan (-0.6%); the eurozone and the rest of the world (-0.3%). IMF G-20 Surveillance Note, “The Global Impact of Escalating Trade Tensions,” July 2018.

- Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, the US can impose trade sanctions on foreign countries that violate trade agreements or engage in unfair trade practices. If negotiations to address the issue fail, the US may take action to raise import duties on the foreign country’s products as a means to rebalance lost concessions.