KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Fed’s reaction function may be changing in subtle but important ways.

- The Fed is increasingly focused on realized inflation—concerned about the implications of slower inflation and growth abroad for the outlook in the US—and leaning into the benefits of a hotter economy and tighter labor market.

- The Fed’s evolution toward a new reaction function has been slow and halting at times.

- We expect the new reaction function will become clearer as time goes on; one way in which that may happen is that the Fed could choose to leave rates at a low level, even if global growth defies the current set of fears and remains resilient. The bottom line is that we believe future rate hikes are unlikely to be compatible with the Fed’s new emphasis.

The current Federal Reserve (Fed) easing cycle has been frequently described as a form of policy insurance. Fed officials have encouraged this line of thinking by making explicit references to the policies of the 1990s, when rates were cut on two separate occasions in response to concerns about foreign developments. In both instances the insurance proved not to be needed, as the US economy continued to grow without much interruption, and in each instance the cuts were subsequently reversed about a year later.

While easy to understand, the focus on the experience of the 1990s may be a misleading guide for understanding current Fed policy. At a minimum, policy insurance is not all that is going on this year at the Fed.

The Fed’s reaction function may also be changing in subtle but important ways. The Fed is gradually shifting its framework toward average inflation targeting, which could significantly change how it will react should inflation move back up to 2%. Fed officials are increasingly vocal about the risks posed by low growth and inflation abroad. Their concern, it appears, is not only about any direct US exposure, but also about the implications of the experience abroad for the future in the US. And Fed officials, Chair Jerome Powell in particular, have started to lean in to rhetoric concerning the benefits of a hotter economy and tighter labor market.

While each one of these shifts may be small, taken together they add up to what could become a significant change in monetary policy. Chair Powell has intimated as much in recent speeches. In a July speech Powell said that future monetary policy will be “discretely different” than it was prior to the 2008 financial crisis.¹ And more recently in his Jackson Hole speech Powell outlined the set of challenges policymakers are currently facing—lower growth, lower inflation and lower neutral policy rates—and he suggested that a new approach may be needed to navigate such an environment.² The emerging message is clear: Fed policy in the coming years seems quite unlikely to resemble policies of the 1990s.

Average Inflation Targeting and the Importance of Realized Inflation

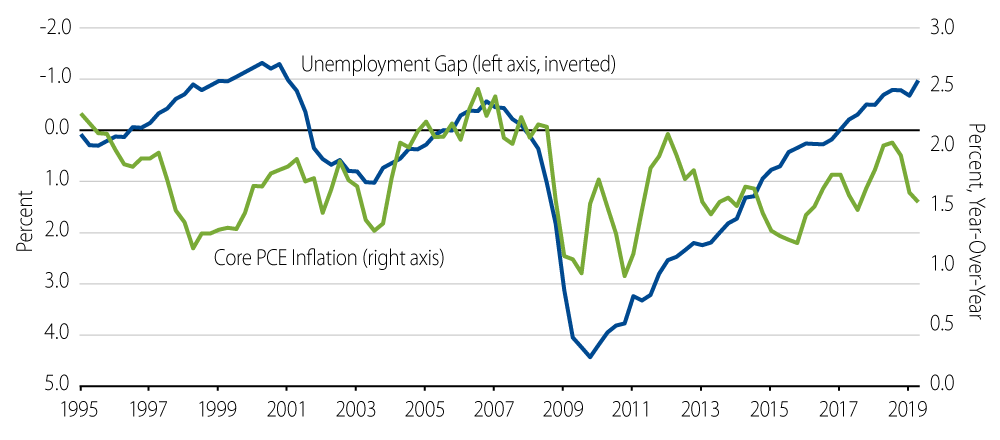

Inflation has again failed to accelerate this year. The core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index (PCE prices minus food and energy prices), which is the Fed’s preferred measure of underlying inflation, remains stuck at 1.6% year-over-year. This has remained unchanged over the last few months, and actually lower than at this time last year, when it briefly touched the Fed’s long-standing inflation target of 2%. The disappointing outcome for inflation stands in contrast to the labor market, which has remained strong, even as macroeconomic uncertainty has risen this year (Exhibit 1).

The disconnect between the labor market and inflation poses a problem for the Fed. If indeed there is no boost to inflation from a tighter labor market, or even if the boost is positive but very weak, it will be hard for the Fed to convincingly argue that inflation is set to climb higher in the near term. This in turn weighs on expectations and puts the inflation goal even further out of reach. The larger issue for the Fed, however, is that rather than being an outlier, this year is just another in a long string of disappointing inflation outcomes.

The good news is that the Fed has increasingly turned its attention to the problem of below-target inflation. The Fed’s ongoing reassessment of its policy framework seems to be moving it closer to average inflation targeting. This new framework would require the Fed to aim for realized inflation above 2% during expansions, in order to offset recessions when inflation is likely to fall below 2%. A reasonable inference is that such a policy would require the Fed to stay on hold even if realized inflation rose to 2%, as the new goal explicitly requires above 2% inflation. In this way, the new framework would be a notable departure from previous Fed practice, which often included raising rates in anticipation of higher inflation, even when the higher inflation wasn’t yet evident in the data.

The Global Context

Global conditions have re-emerged as a central consideration for the Fed this year. It is normal for the Fed to monitor global growth, and occasionally signs of a sharp downturn in global activity will even push the Fed to respond in some way. The bar for such action is fairly high, however, because the external sector is usually a small component of US growth.

Regardless, the Fed’s concern about global conditions seems to be slightly different this year. In addition to monitoring the risks of a global slowdown, the Fed is also paying careful attention to how other central banks are navigating the current environment. The Fed is beginning to consider the experience of other central banks because it seems likely that many of the challenges they face will impact the US too, sooner or later.³ In particular, low growth and low inflation have increased the probability of nearing the lower bound in interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan already have rates near the lower bound, and they are struggling to come up with appropriate responses. While US interest rates are currently above zero, there is an understandable fear that US short rates will return to zero at some point. The challenges bedeviling the Fed’s foreign counterparts have certainly registered among Fed officials and, we believe, play a role in their current decision-making.

There are at least three lessons from the experience of foreign central banks that have interest rates near the lower bound. The first is that limited efficacy of lowering policy rates means that creativity will be required to find other policies to stimulate demand. The second is that the other, creative policies will likely introduce complications, which could in turn require their own fixes. That is why the ECB has signaled that its next round of interest rate cuts will be part of a package of measures, likely including tiered interest rates and quantitative easing, in an attempt to both stimulate demand and address these other complications. The third lesson is that it is much better not to be near the lower bound, or at a minimum it’s desirable to avoid the lower bound for as long as possible.

Focusing on how foreign central banks are struggling with policy rates near the lower bound is a shift in emphasis for the Fed. It’s well established that the Fed would respond as needed should a sharp global slowdown threaten the US expansion. The Fed has done so in the past, and Fed officials regularly reassure investors about their willingness to do so again in the future, if needed. Easing policy to combat a sharp slowdown is nothing new. In contrast, it would be novel if the experience abroad—and specifically the challenge presented by the lower bound in interest rates in a foreign country—motivated the Fed to err on the side of more accommodative policy now, even in the absence of a sharp global slowdown, in order to avoid facing similar circumstances in the future.

A Renewed Focus on Growth

The final element of the Fed’s changing reaction function is an increased emphasis on growth. Chair Powell’s now standard practice is to laud the benefits of a tighter labor market at the beginning of every set of remarks. His recent speech in Jackson Hole was no exception. In a speech titled “Challenges for Monetary Policy,” Powell devoted his second paragraph to a discussion of increasing labor force participation, rising wages, training new workers and giving second chances to previously marginalized workers. Powell also implied a goal of spreading the benefits of the expansion more broadly, citing specifically the improved conditions for African Americans and people in low- and middle-income communities.

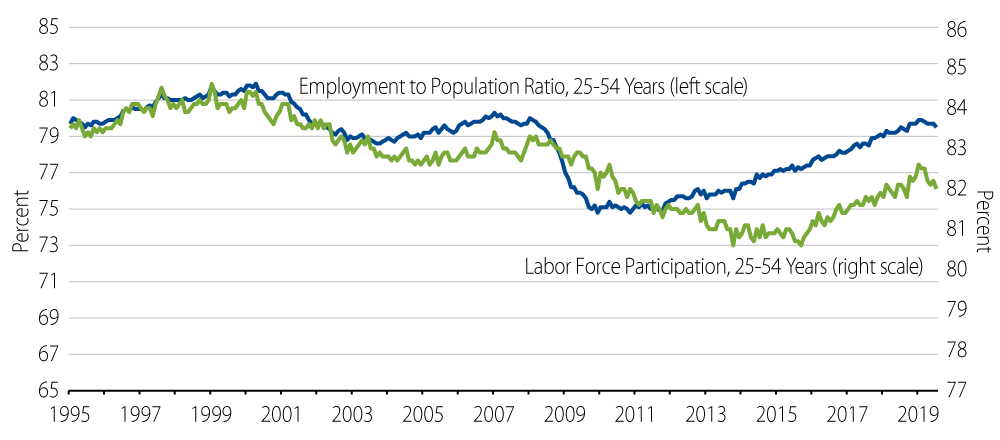

Powell’s speech included no indication that the US economy was near its limit on any of these dimensions. This conclusion is supported by the available labor market data. For example, the prime-age employment-to-population rate is still materially below its peak in 2000, in large part due to the still-low participation rates among prime-age men (Exhibit 2). There seems to be little if any debate that more growth, as well as more widespread growth, is among the Fed’s foremost aims right now.

The renewed emphasis on growth is a natural consequence of the previous observations on the Fed’s reaction function. The primary reason why a central banker would seek to restrain growth is if an excess of demand threatens to push up prices unsustainably. It follows, therefore, that low inflation serves as a green light for central bankers to pursue more growth. In addition, there is a chance that more growth could lessen the risks posed by the lower bound in rates. This could happen in at least two ways. Additional growth could support inflation expectations, thereby lowering real rates and providing more accommodation when nominal rates are near the lower bound. Additional growth could also lead to a virtuous cycle of more investment and then higher productivity, which would then lead to higher neutral policy rates. While neither outcome is assured, they both go in the same direction, thereby bolstering the Fed’s focus on growth.

Conclusion

The challenge for investors is that the evolution of the Fed’s reaction function has been slow. Chair Powell’s recent speeches have illustrated the halting progress. In speech after speech Powell has shown the way forward for the Fed, as illustrated by many of the excerpts discussed earlier. But Powell’s speeches have also contained a fair amount of debris from the present, not to mention residue from the past. The Jackson Hole speech was a case in point. In addition to a clear-eyed discussion of the challenges posed by the new environment and the need to boost growth here in the US, Powell also said “Inflation seems to be moving up closer to 2 percent” and, even more confusingly, mentioned that in reference to the trade conflict “there are no recent precedents to guide any policy response to the current situation.” Both of those statements may be true, but they also seem immaterial to the bigger picture. Investors were left to guess whether the Fed’s actions will reflect the new reaction function, or whether the Fed will be more reactive to the most recent set of headlines or data. The confusion has become typical of Fed communications.

Our view is that the Fed’s changing reaction function will become increasingly clear over time. A return to the discussion of policy insurance, which was briefly mentioned at the beginning of this note, can help illustrate one way this could potentially play out. In the near term the Fed’s actions may indeed resemble the experience of policy insurance in the 1990s. As the global growth outlook becomes better or worse, the Fed may take out more or less insurance. That much seems uncontroversial.

The real difference in Fed policy may become apparent only if global growth turns out to be more resilient than currently feared. If the Fed is still stuck on the 1990s playbook, a better-than-feared outcome on global growth could lead it to take back the insurance cuts with a series of hikes, perhaps as early as next year. If, however, the Fed’s reaction function is indeed changing, the Fed could choose to continue to provide accommodation, even if growth were to hold up. In that case, no future hikes would be forthcoming. Rate hikes would be simply incompatible with the Fed’s new emphasis. Leaving rates at a lower level would be the most obvious way to meet the new goals of higher realized inflation, avoiding the fate currently facing foreign central banks near the lower bound in interest rates, and boosting growth in the US. And that, accordingly, is where we suspect the Fed is headed.

- “The world in which policymakers are now operating is discretely different in important ways from the one before the Great Recession.” – Chair Powell, Monetary Policy in the Post-Crisis Era, July 16, 2019

- “The current era has been characterized by much lower neutral interest rates, disinflationary pressures, and slower growth. We face heightened risks of lengthy, difficult-to-escape periods in which our policy interest rate is pinned near zero. To address this new normal, we are conducting a public review of our monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications—the first of its kind for the Federal Reserve.” – Chair Powell, Challenges for Monetary Policy, August 23, 2019

- “Average inflation rates for the other major advanced economies have declined by almost half, while the inflation rates of major emerging market economies are less than one-fifth of what they were. Indeed, with few exceptions, we are all facing lower rates of interest, growth, and inflation.” – Chair Powell, Monetary Policy in the Post-Crisis Era, July 16, 2019