Executive Summary

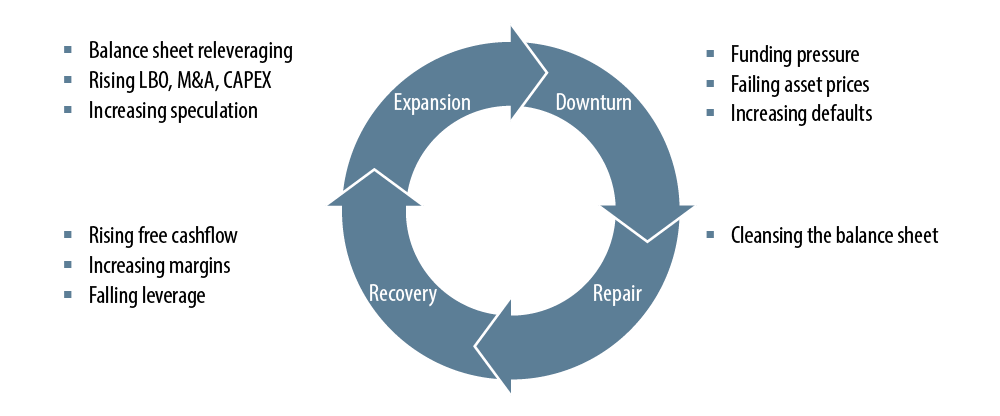

- A credit cycle follows the direction of the broad economy and is generally considered to have four distinct phases: expansion, downturn, repair and recovery.

- The current business cycle is one of the longest on record, and has been supported by low but stable global growth and significant ongoing central bank intervention.

- Economic conditions generally remain conducive to a continuation of the current credit cycle both globally and domestically.

- Many investors are postulating that the end of the current expansion phase is imminent. While we believe that the transition to a downturn will happen one day, we feel that the catalysts are not yet in place for this to occur in the near term.

- While both local corporate fundamentals and technicals should underpin a continuation of the credit cycle in Australia, we note that domestic credit spreads are currently tighter than long-term averages, and increased global volatility will impact valuations.

- We continue to stay invested in credit, but for now prefer to focus on shorter-dated securities within more defensive sectors, offering decent carry and stability of cashflows.

There is no doubt that we have been living through an extraordinary period of economic stability, characterised by low but stable global growth and fueled by central bank largesse, persistently low or even negative interest rates and a seemingly insatiable appetite for risk assets. Given this extended period of economic expansion, and multi-year strong credit performance, the question naturally arises as to where we are in the credit cycle and whether current valuations warrant further outperformance.

The current credit cycle began in 2010, making it one of the longest credit cycles in the modern era. While all expansion phases of a cycle must come to an end, we believe that old age alone is not a catalyst for the turn in the credit cycle. In a recent Western Asset paper, Where Are We in the Credit Cycle?, we assert that forecasts of an imminent end to the US expansion phase are not supported by the current environment or existing data.

In this paper, we assess whether this position holds true for Australian credit markets. What we find is that the economic backdrop is well balanced, corporate fundamentals are solid and market technicals remain supportive. Add to these observations a relatively benign default environment and cautious central banks, and we can construct a strong argument that, absent any exogenous shocks, the domestic credit cycle still has some room to run. Credit spreads, while tight compared with recent experience, should remain well contained throughout the remainder of 2018.

The Credit Cycle: A Primer

Previous credit cycles have tended to follow the direction of the broad economy. Such cycles are generally considered to have four distinct phases: expansion, downturn, repair and recovery (Exhibit 1). All credit cycles ultimately end in a downturn. While this outcome is inevitable, the timing of transition from expansion to downturn is not and the turning points are never easy to predict. Credit cycles do not die of old age. They are, however, typically presaged by a turn in the business cycle, tightening lending standards and heightened funding costs. As the availability of capital falls, and the cost of servicing debt increases, defaults rise as companies that had over-levered in the good times struggle to meet financial obligations under the weight of excessive debt loads and falling revenues.

Phases of a Credit Cycle

The current US economic cycle has extended well beyond the duration of the average expansion; fueled by a combination of historically low interest rates and central bank policies such as quantitative easing (QE) that have infused large levels of liquidity into the global economy. At 106 months, this is now the second longest business cycle in US history.

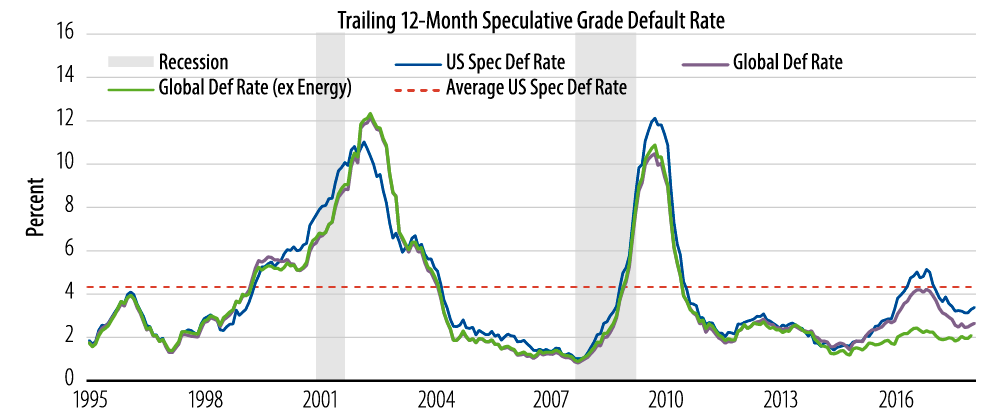

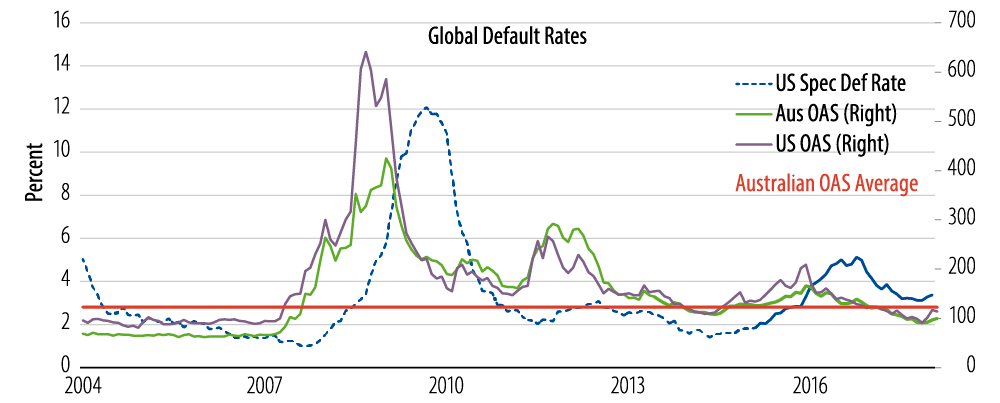

Similarly, the default cycle has remained benign for much of this period. While 2015 saw a pickup in US defaults (Exhibit 2), that was focused in the energy/commodity sectors, and remained relatively well contained. Defaults have since retraced and the trailing 12-month US speculative default rate sits at 3.37% as of March 2018, remaining under its long-term average of 4.30% and indicative of a corporate sector that is currently not under excessive financial stress. Globally, the default figure (S&P, speculative grade, all sectors) is 2.62% as of March 2018.

Has the Credit Cycle Run its Course?

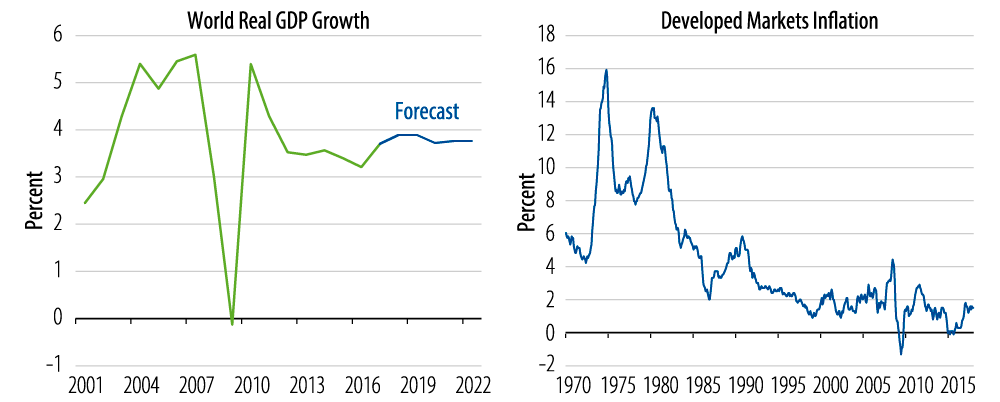

In general, global economic conditions remain conducive to a continuation of the credit cycle. The global economy is entering a period of synchronized growth, with the IMF expecting global growth of 3.9% in 2018 and 2019 (Exhibit 3). While central banks are moving towards an unwinding of their QE programs and raising rates, momentum is slow as a lack of inflationary pressures persist across most developed economies. Global balance sheets are expected to remain substantial for a prolonged period1.

Steady as She Goes

(Right) Source: Bloomberg. As of 31 Mar 18

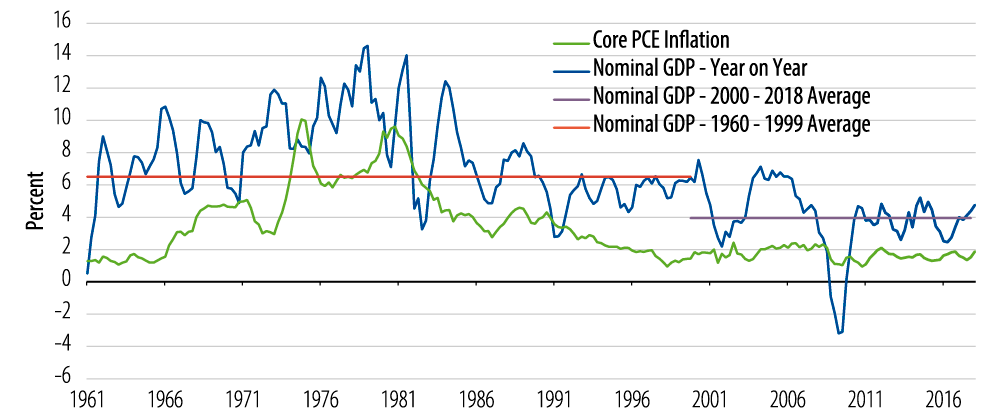

Turning to the US, we can see that despite the extended period of economic growth and strong jobs growth, the core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Index, the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) preferred measure of inflation, continues to run below its target of 2% (Exhibit 4). Ongoing underemployment and persistently low wage growth are limiting any imminent breakout in inflation, providing us with a degree of comfort that the US economy is not overheating2. Indeed, US GDP continues to run below that of previous expansion phases. In previous cycles, nominal growth rates of over 6% on average were recorded as the expansion phase neared its end. US nominal GDP is currently running closer to 4% per annum and is exhibiting enough spare capacity to allow for further growth.

US Inflation Remains Elusive

The Fed is well on its way down the path of interest rate normalization, albeit from historically low levels, and has begun to unwind its QE program. Importantly, the process has been slow, and the Fed has stated often that further increases will be well telegraphed and gradual as it remains attuned to the risk that any policy error could derail the recovery.

Against this backdrop, US corporate balance sheets3 remain in good shape. The latest US reporting season was robust and recent US tax cuts have seen earnings improve. In general, while leverage levels are rising, debt coverage levels remain high and corporate profitability continues to improve. Cash levels have been built up and access to capital remains open. US corporates have improved their ability to deal with volatility in funding markets. For more detail, see Where Are We in the Credit Cycle?

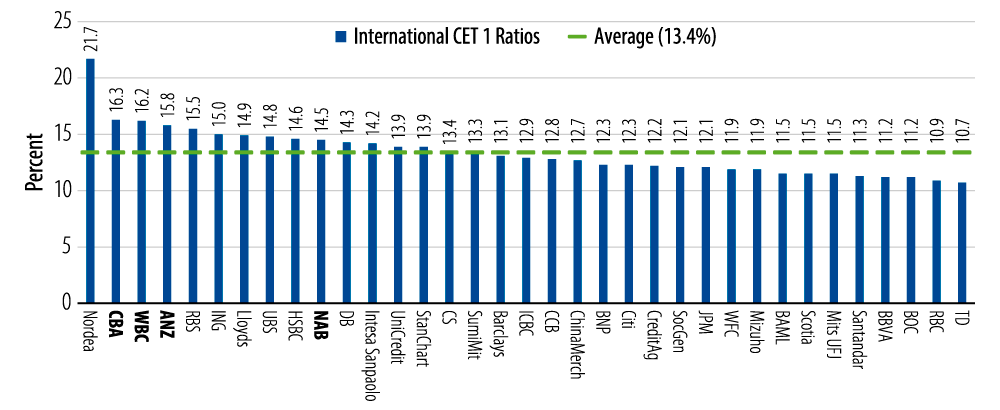

The banking sector also continues to be very well capitalized. Since the onset of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), global banks have been subjected to significant regulatory oversight, resulting in improved balance sheets and enhanced liquidity. Today, US banks are fundamentally more sound than what they have been at any time in the past 50 years, driven by regulatory changes making them more “utility-like”.

A look at European markets reinforces our current positioning. Growth in Europe continues to move at an above-trend pace of 2.4%. However, recent soft data are indicating that a continuation of this growth may not be forthcoming. The IMF estimates European growth of 2.4% and 2.1% for 2018 and 2019, respectively. We believe that the European Central Bank (ECB) will remain accommodative for the foreseeable future, with rate normalisation not expected until 2019. While shifts in QE are expected in September 2018, and likely to drive some spread volatility, we do not envisage a reduction in the ECB’s balance sheet until 2020. This should continue to be supportive for European corporates funding requirements. Speculative default rates in Europe remain well contained, currently sitting at 2.09% as of March 2018, against a long-run average of 3.24% (from March 2000).

The Australian Credit Market in the Global Context

How does the global environment impact the Australian credit cycle? Domestic spreads tend to display lower volatility than global peers due to Australia being a strong investment-grade market with a much shorter duration than global markets4. It remains the case, however, that regardless of the domestic economic outcomes, the performance of the Australian credit market is largely dictated by movements in offshore, and in particular US, markets. Historically, there has been a strong correlation between US speculative-grade default rates and AUD corporate spreads (Exhibit 5).

When the US Sneezes the Australian Credit Market Catches a Cold

This relationship is no more evident than during the GFC, when, despite Australia not entering into a recession by virtue of a commodity boom, liquidity dried up and domestic credit spreads widened significantly. While we experienced some defaults, this was limited to a handful of domestic financial institutions that did not have significant debt market exposure (Allco and Babcock and Brown)5. Why did our spreads widen if there was neither a domestic economic recession, nor a subprime housing sector? The answer is that global funding markets are interrelated.

Australian credit markets are truly global in nature. Approximately 50% of the value of the Australian corporate bond market6 is issued by global companies. Additionally, Australian institutions derive much of their funding from offshore markets (in particular the major banks). When global liquidity seized up, it flowed through to domestic balance sheets. The Australian banks needed government guarantees on their debt to continue to fund themselves. Domestic corporates had been just as profligate as their global counterparts in increasing leverage and front-loading their debt profile, so when the availability of capital dried up, these institutions got hit just as hard.

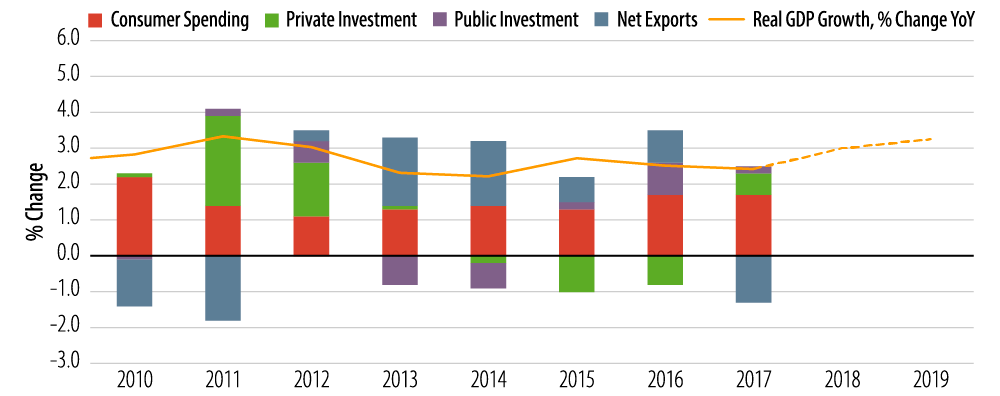

The Australian Economy Continues to Defy Gravity

Australia has not seen a recession in 27 years, recording the longest period of continuous economic growth in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Australia managed to navigate the post-GFC period with a combination of good fortune and good economic management. The commodity boom provided substantial support during the GFC; however, that support has since waned, resulting in a multi-year drag on GDP as the mining CAPEX story unwound. In its stead, a housing construction boom, and a burgeoning export sector (linking us to the growth in Asia and to China in particular) led by tourism and education have allowed for the transition from mining to a broader recovery to occur without undue pain. As the residential construction boom tapers, Australia now has a significant pipeline of infrastructure projects and an upswing in its terms of trade to underpin growth over the coming periods. GDP currently sits at 2.4%, with Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) forecasts of 3% and 3.25% for 2018 and 2019, respectively. Importantly, growth remains well balanced and supportive for domestic companies. Unemployment has remained stable and now sits at 5.5% with ample spare capacity and inflation remains below the RBA’s target band of 2% to 3%. Whichever way you look at it, Australia has certainly been, and continues to be the lucky country.

The Shifting Composition of Australian Growth

If there is a downside to this picture, it is clearly the consumer. Household debt-to-income has risen exponentially, wages have stalled (recording a cumulative growth rate of 0.2% in real terms since 2012) and savings rates continue to fall. Key risks remain in the housing market, with the rise in investor and interest-only loans.

The active use of macro-prudential regulations by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) have been successful in reducing the risks of the housing sector overheating. The RBA is cognisant that households remain susceptible to any significant upward shifts in monetary policy and has subsequently been reluctant to raise the cash rate above the low of 1.5% set in August 2016. We do not see any obvious driver for this policy setting to change in 2018.

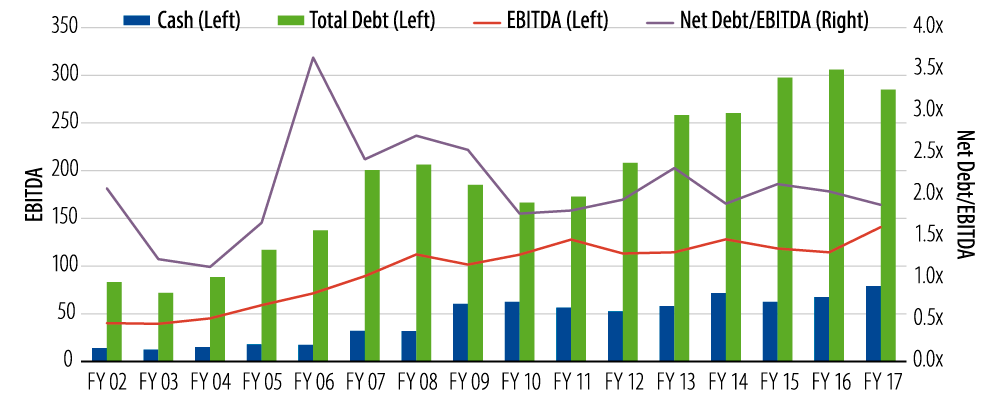

Australian Corporates Remain in Good Health

Corporate Australia is coming from a position of relative strength. The latest corporate earnings season has shown a continuation of this trend with improved revenue, stronger earnings and a slightly more optimistic outlook. Corporate credit quality remains sound. Gearing ratios generally remain towards the lower end of target ranges (or below) and debt coverage ratios remain healthy (Exhibit 7). To date, corporate treasurers have generally been well behaved, with returns to shareholders via dividends and buybacks being largely credit neutral.

Corporate Fundamentals Remain Robust

A deeper look into the balance sheets of many Australian corporates highlights that corporate treasurers have become more prudent in the management of their debt profile post-GFC. Heading into the GFC many corporates relied upon excessive short-term bank funding, assuming that refinancing would continue to be cheap and abundant. The GFC saw banks become reluctant to lend to corporates and the cost of debt increased as companies had to source funding from capital markets.

In recent years, the tenor with which banks are willing to lend has extended out to five years (and beyond), with a deepening domestic bond market providing companies the opportunity to raise debt funding out to 10 years (up from five years pre-GFC). This evolution has seen the duration of the AusBond 0+ Corporate Bond Index increase from 3.0 years in Sep 2014 to 3.8 years in April 2018. Corporate treasurers continue to use offshore markets as a primary source of debt with maturities longer than 10 years.

Balance sheet funding is now more balanced across sources of funding, geographical diversity and debt maturity, leaving Australian corporates in a stronger position to deal with potential reductions in capital availability from any one source.

Turning to the domestic banks, they are now exceptionally well capitalized, making them some of the safest banks in the world (Exhibit 8). APRA has required the Australian banking sector to be “unquestionably strong” with regulation also aimed at improving liquidity (ability to fund itself in a liquidity event) and better matching assets and liabilities (reducing its reliance on short-term funding). APRA has also engaged actively in macro-prudential measures aimed at slowing the flow of credit to the housing sector and shielding the domestic banks from egregious increases in risky lending practices.

Australian Banks Are Some of the Safest in the World

Technical Tailwinds Continue to Support Spread Products

Global QE programs and excessively loose monetary policy have resulted in historically low rates globally, with negative interest rates being evident in large parts of the developed world. This backdrop has driven an insatiable appetite for risk assets as investors hunt for yield globally—driving spreads tighter and reducing the duration and magnitude of any bouts of volatility. While the process of normalisation has begun, it will be a gradual process and we would expect high levels of demand for income-producing assets to continue.

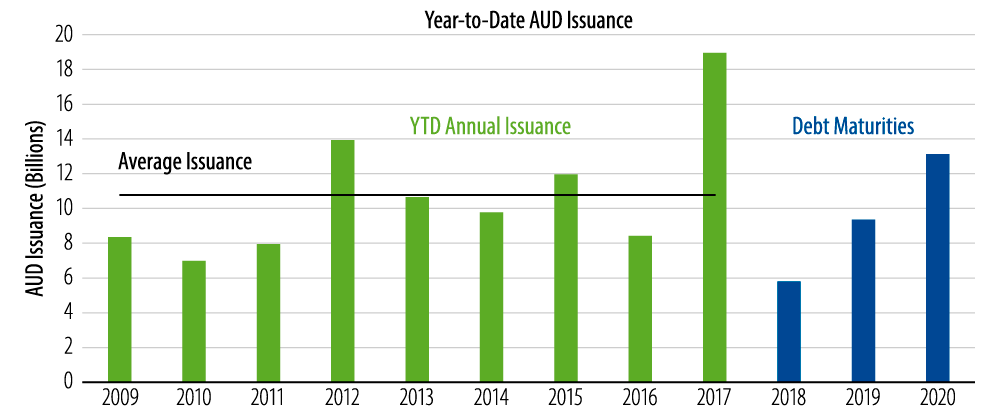

Additionally, corporate issuance is likely to fall for the remainder of 2018 and into 2019 (Exhibit 9). 2018 is expected to be the lowest maturity year in Australian credit markets since 2013, with only a slight pickup in 2019. Refinancing requirements are only $6 billion this year across corporate issuance, and we would expect some of these issuers to not refinance. Additionally, modest growth CAPEX requirements and to date, limited debt funded corporate actions, should also act to curb any significant supply of corporate issuance into the domestic market place. As mentioned earlier, with more geographically diverse debt profiles, treasurers may fund offshore, to the detriment of local supply.

Refinancing Requirements Going Forward Are Limited

Where to From Here?

Absent any exogenous shocks to the system, we do not see any imminent threat to the current credit cycle, either globally or domestically, for the remainder of this year.

In assessing the local environment, we appreciate that spreads have come a long way since the GFC and are now sitting at or near long-term averages. While we believe that we are being adequately compensated for default risk at these levels, there is limited upside to be gained from taking on too much risk. The cycle is clearly getting on in age and we feel that domestic credit spreads will be largely range-bound for the remainder of this year.

What does that mean for our domestic credit strategy? We continue to stay invested in credit, but for now prefer to focus on those sectors that offer decent carry and stability of cashflows; in particular infrastructure, utilities and property. While the banking sector clearly has its problems, we remain of the view that globally banks remain on sound footing and we are happy to accumulate as valuation opportunities arise.

Investing in shorter-dated credit will act to minimize any volatility that may occur as the market slowly moves towards the turning point in the cycle. In this environment, bottom-up analysis is key. Avoiding companies that have exposure to more cyclical parts of the economy (i.e., exposure to retail in an environment of a stressed consumer) will serve portfolios well. This focus on the fundamentals will also continue to drive our tactical positioning across portfolios; as we look for opportunities to invest in primary issuance that offer excess premiums and also take advantage of any short-term technical volatility that may result in mispriced investment opportunities in the secondary market.

Endnotes

- For a more detailed assessment of this trend, see the recent Western Asset paper published in May 2018, Central Banks: The Slow Road to “Normal”.

- For a more detailed discussion on where we are at from a global perspective and what our expectations are for the US yield curve, refer to 2Q18 Market & Strategy Update by Western Asset CIO Ken Leech.

- US corporates are used due to the size and depth of the US market.

- AusBond 0+years Credit Index is 3.82 years in duration with an average rating of A+, against the Barcap US Credit Bond Index of 7.04 years duration and an average rating of A as of 30 April 2018.

- Both Allco and Babcock and Brown utilised the ASX listed bond market to fund their debt requirements. There was no exposure to these institutions in institutional credit indicies. In addition, US financial institution Lehman Brothers had debt issued into the Australian market at the time of default.

- As reflected by the AusBond 0+yrs Credit Index