KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Any run of higher prices caused by supply disruptions or even overly expansive fiscal policy will soon run its course.

- Supply-chain disruptions do not have to vanish for the price process to reverse; disruptions need only to ease.

- There is no evidence for increases in wages autonomously driving higher inflation.

- With demand for goods and services still restrained, higher wages are not going to drive higher prices.

- Without an acceleration in demand growth and with a normalization of supply and supply growth, goods prices must moderate, even decline.

- Aggregate demand has not shown any acceleration from pre-Covid trends, contradicting the contention that Fed policy has caused the economy to run too hot.

There has been a host of articles in the financial press recently on inflation. That is understandable given that measured increases in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index have both registered rates of increase not seen in 40 years.

At Western Asset, an enduring pillar of our fixed-income investment strategies has been our position on inflation and how we think inflation will evolve. We have presented these views in various papers and blog entries over the last year plus. Here, rather than restate those views, I will instead address head-on the various statements and descriptions of recent inflation with which I disagree.

Misconception #1: Inflation has been flaring for more than a year.

Year-over-year inflation rates topped 4% in May 2021, and such rates have moved steadily higher since then. The common perception is that the US has been experiencing rising inflation since late-2020. However, just as the 30% GDP growth in 3Q20 was not a boom but merely a rebound from the even larger, temporary declines experienced during the shutdown, so too the price increases seen through summer 2021 were merely a reversal of declines experienced during the shutdown. No one talked about or feared deflation during the shutdown and rightly so. For the same reason, it is inaccurate to describe the price rebounds of 2020 and early-2021 as inflation, at least not the kind of inflation that is a national policy problem.

Exhibit 1 shows both one- and 12-month inflation rates in the core CPI. The burst of prices over July-September 2020 was clearly merely a reversal of shutdown-induced declines, but only a partial one. As you can see in Exhibit 2, neither the headline nor core CPI price indices had re-attained pre-Covid inflation trend levels by late-2020. It took that second price burst, over March-June 2021, for price levels to fully recover from shutdown-induced “deflation” (along with the effects of increases in used-car prices driven by a shortage of processor chips for new cars).

During that episode, various service sectors reopened, such as hotels, airlines and recreational facilities, and prices for these sectors rebounded back to—but not through—the levels in place prior to the shutdown. Despite the artificial nature of this so-called inflation, YoY (12-month) inflation rates were rising then, because those rates were calculated against the still-restrained price levels of a year earlier.

Now, prices have flared up again over the last four months. These are gains over and above the declines during the shutdown, and these are a cause for concern and potentially a target of policy. However, as I will argue in the following, why I think the recent price burst largely reflects supply-side congestion and is not due to excessive demand growth nor to any supposed miscreance by the Federal Reserve (Fed) or federal government.

Misconception #2: An increase in the money supply must equal higher inflation.

Our approach to inflation is first and foremost a monetary one. The process of sustained price increases that can push interest rates higher can only be driven by overly expansive monetary policy, which creates the purchasing power to sustain higher and rising prices. Without that creation of purchasing power by the monetary authority (central bank), any run of higher prices caused by supply disruptions or even overly expansive fiscal policy will soon run its course.

Having said that, there are a host of factors presently that can lead to temporarily faster growth in the money stock. Up until the 1980s, zero interest was paid on checking account balances. With substantial rates of interest available on other deposits and fixed-income investments, checking account balances were held primarily to foster/finance spending, and spending growth (and inflation) in the economy correlated closely with growth in the money stock.

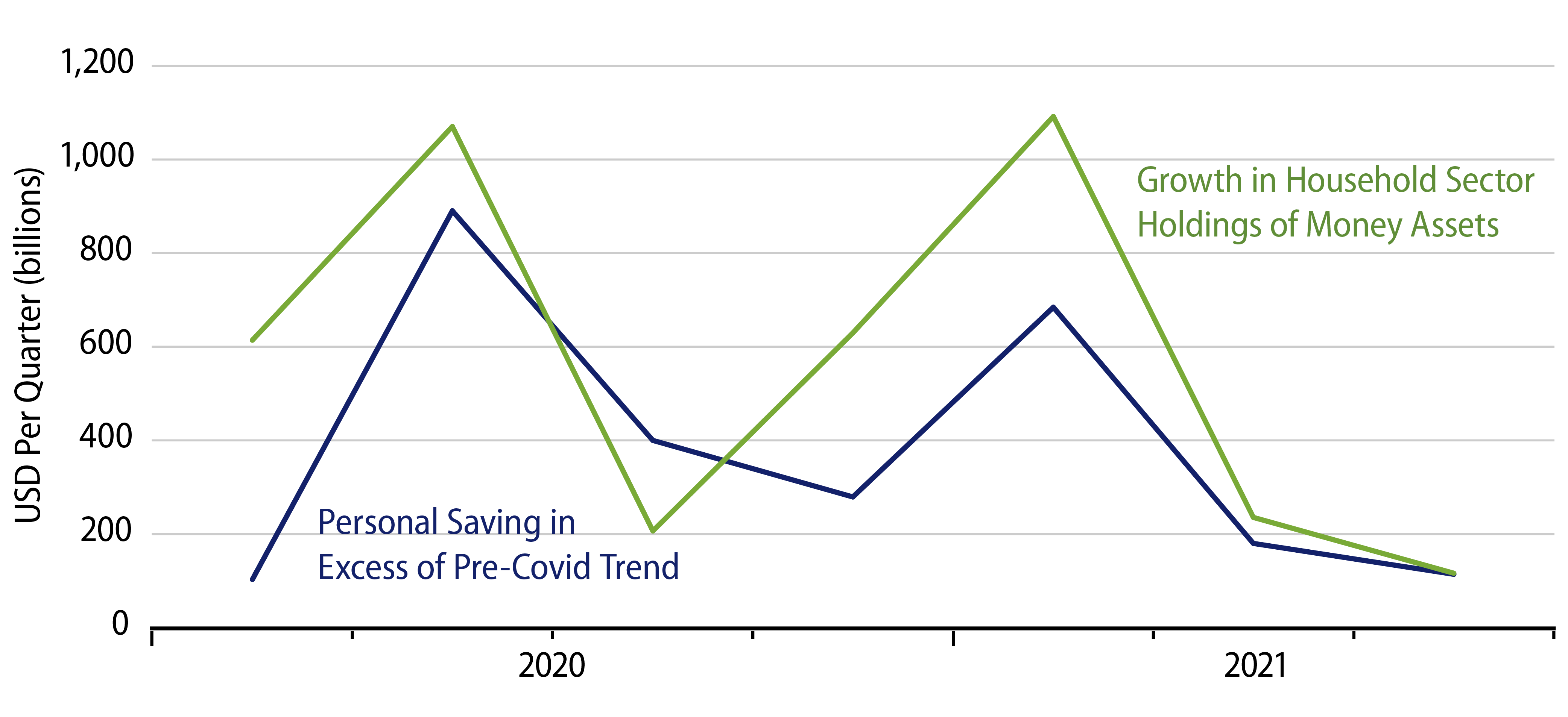

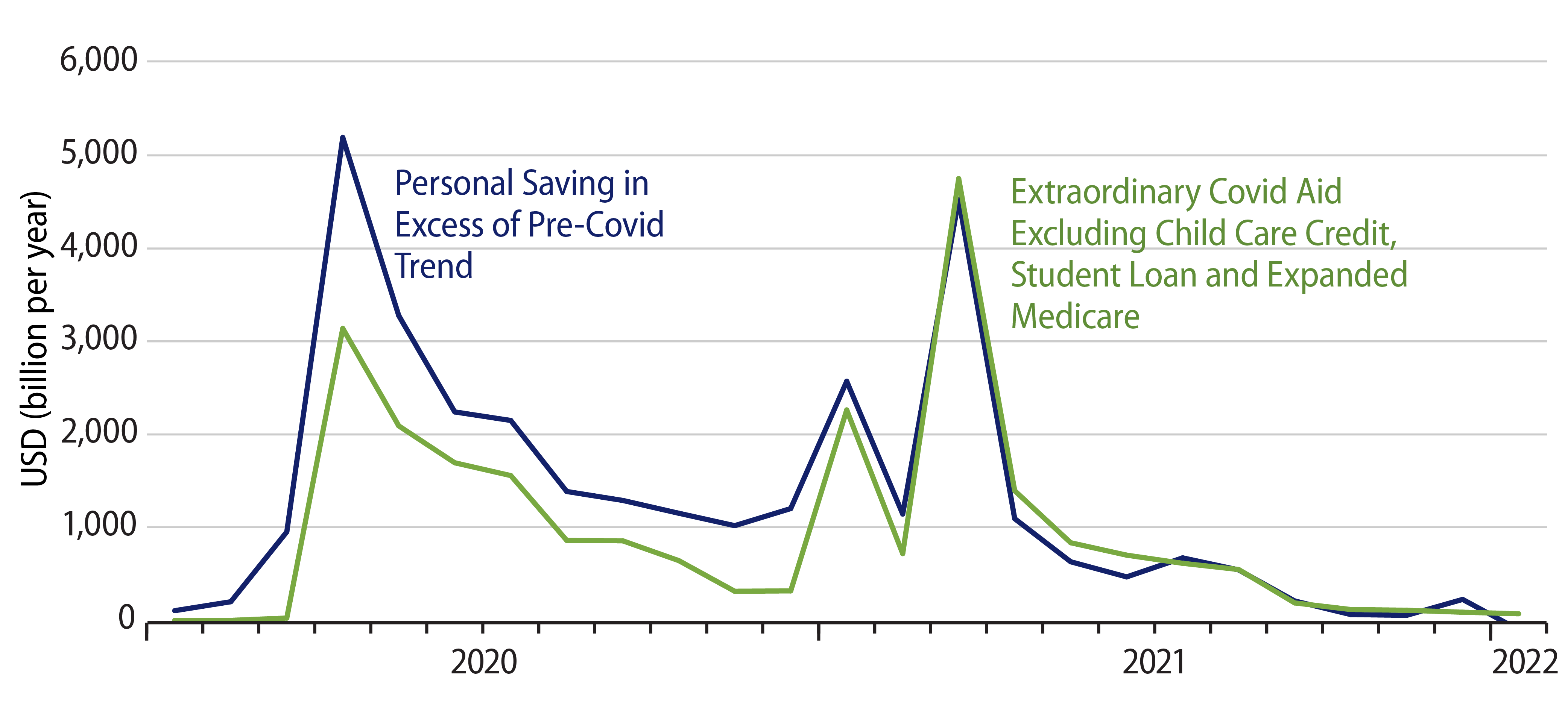

In the current financial system, with interest freely available on checking account balances and with those rates quite competitive with the interest paid on non-transaction accounts, much of the ups and downs in checking account balances—hence money stock growth—cohere with saving decisions rather than spending decisions. The stimulus payments provided by the federal government to individuals over the Covid experience have been almost fully saved, and much/most of that saving has gone into bank deposits that are included in the money stock. You can see this in Exhibit 3.

Furthermore, whereas pre-global financial crisis (GFC) bank lending and deposit-creation were restrained by the availability of reserves, with the supply of reserves controlled by the Fed, presently, reserve requirements are gone and bank credit creation is restrained instead by capital requirements. As a result, ups and downs in the money stock have little or nothing to do with Fed policy operations.

The evidence for these assertions lies in the course of nominal spending in the economy (nominal GDP). As stated earlier, the accelerations in nominal spending that feed sustained accelerations in inflation can come only from the Fed. In fact, Fed attempts to achieve faster spending growth and faster inflation failed throughout the post-GFC period, and the same is true for central banks across the developed market (DM) world. Even presently, once the Covid shutdown of 2020 was followed by a reopening of the economy in late-2020 and 2021, spending rebounded back to the trend pace that was in place prior to Covid, but there has been no net acceleration (Exhibit 4).

I believe that even in the absence of extraordinary Fed policy measures, merely the reopening of the US economy would have allowed nominal spending to retrace the declines that occurred during the shutdown. If growth in the money stock were stimulating the economy—thence inflation—further, we should have seen a net acceleration in spending versus pre-Covid trends. This has not happened. As a result, I conclude that despite intentions to the contrary, Fed policy has not served to stimulate either the economy or inflation in the past two years.

Misconception #3: Faster wage growth always leads to higher inflation.

Rapid wage growth is a consequence of inflation, not a cause of it. While we often hear references to “wage-push” inflation, there is no evidence for increases in wages autonomously driving higher inflation.

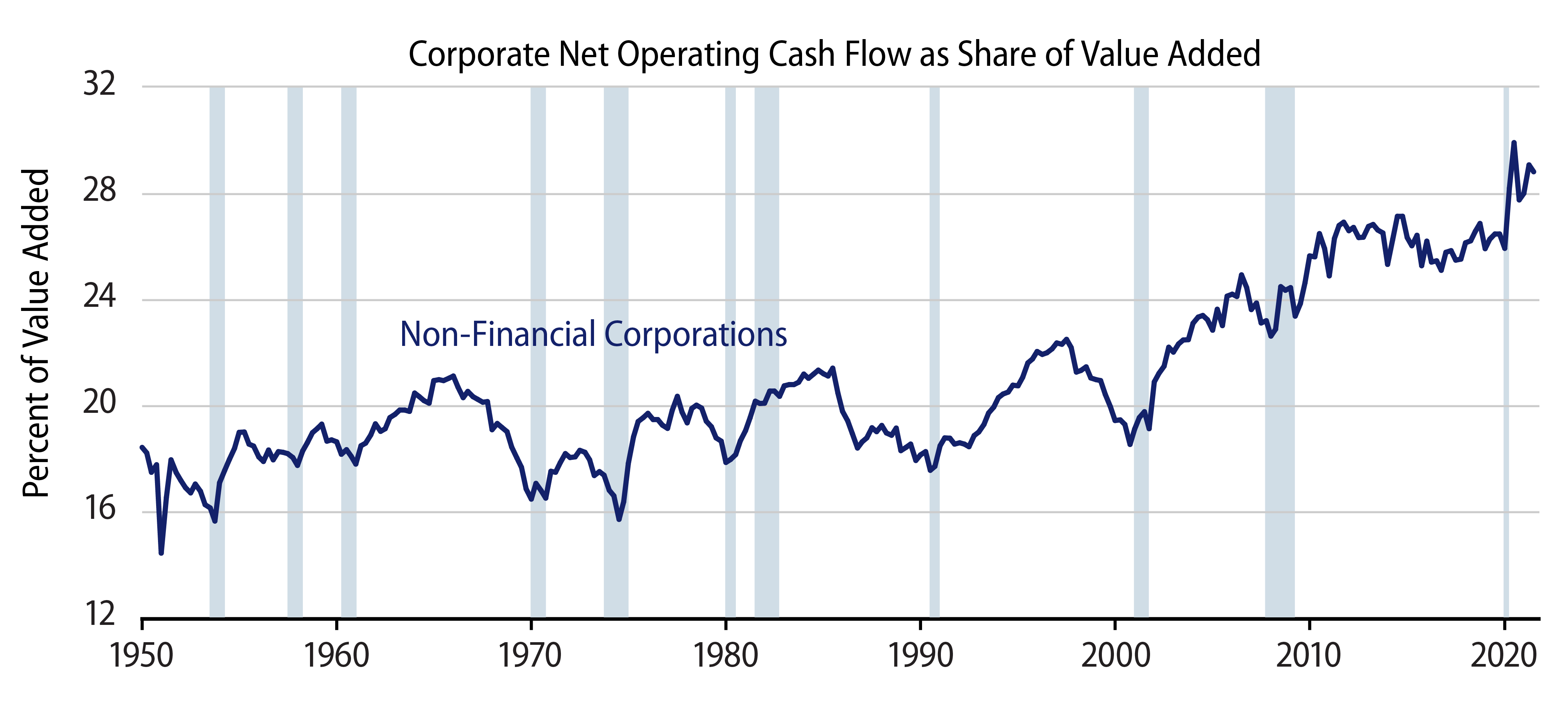

Meanwhile, there are various factors that can drive up wages unrelated to inflation trends. I believe many of the wage increases we have seen in the past year represent a reversal of post-GFC experience. During the GFC of 2008-2009, businesses cut operations to the bone in an all-out effort to survive. Staffing was reduced to minimal levels, driving unemployment higher in the process. The economy turned around, and businesses gradually built back staffing, but wages remained relatively restrained, which is to say that the share of business output that went to workers—rather than capital spending or profits—declined to very low levels, while the share of output retained by businesses (after-tax cash flow) soared to new heights.

That process appears to be reversing in the current economy. Unlike during the GFC, federal aid extended during the Covid pandemic was broadly provided to companies to keep them afloat and to sustain their payrolls, even as workers were provided extremely generous unemployment benefits, thus reducing the need/incentive to find work. As a result of these measures, the labor market has shifted to a sellers’ (employees’) market, rather than the buyers’ (employers’) market that prevailed during and immediately following the GFC.

With demand for goods and services still restrained—i.e., growing at pre-Covid trends—higher wages are not going to drive higher prices. Rather, we would look for profit margins to begin to be squeezed back toward historical norms.

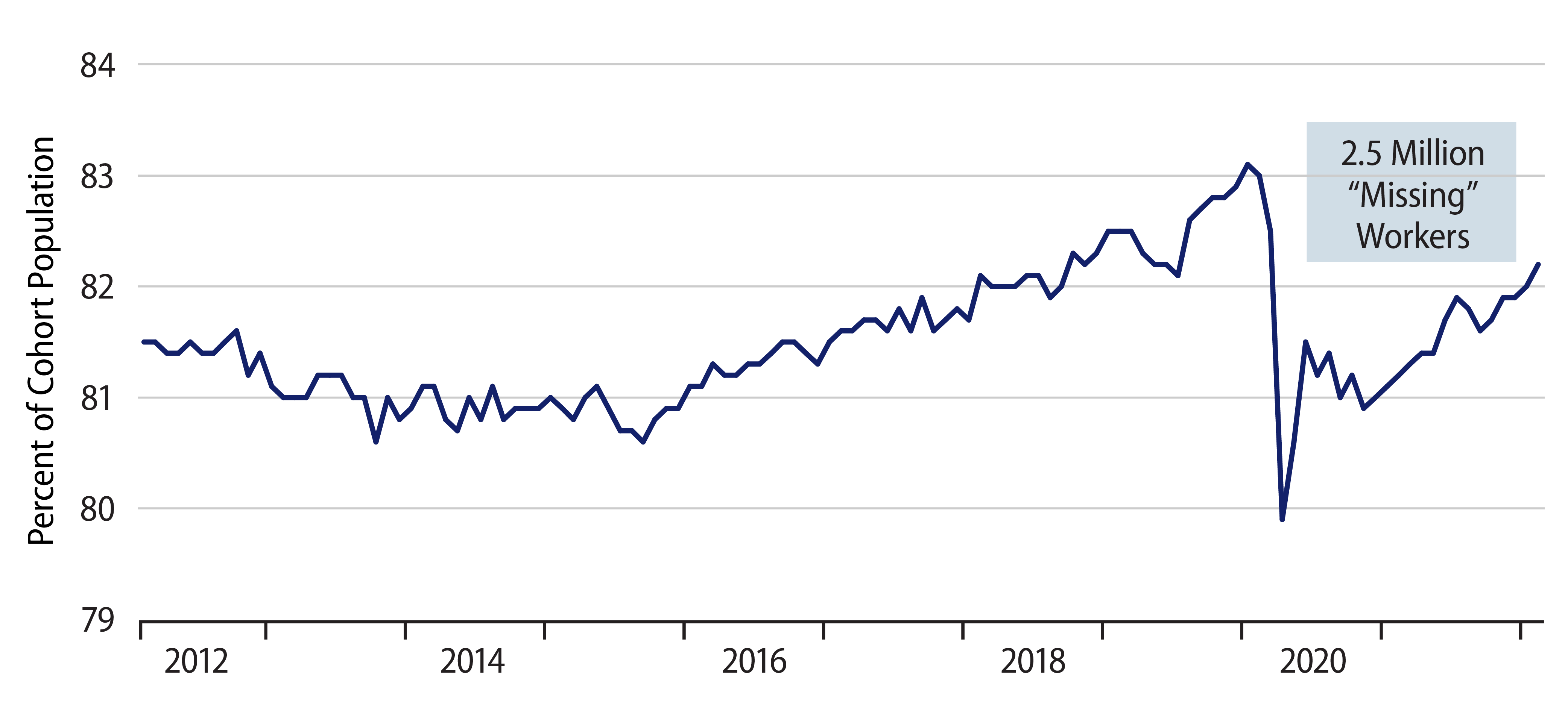

Meanwhile, the generous unemployment compensation provided by the CARES Act and other Covid relief programs has expired. Studies found that the expiration of extended unemployment benefits in December 2014 drove both an increase in labor force participation and economic growth in 2015, six years into the post-GFC expansion. Exhibit 6 shows prime-age labor force participation rates rising in 2015 and after. I look for a similar boost to labor supply with the expiration of CARES Act unemployment relief. The indications are that this increase has already begun.

Misconception #4: Supply chain disruptions will cause sustained inflation.

There is no denying the fact that a reduction in supply—opposite stable demand—will result in an increase in prices. Indeed, as stated earlier, the increase in goods prices occurring over the last four months can be attributed to the supply-chain disruptions and port congestion the US experienced in 2021. Economic analysis is just as clear, however, that those supply reductions lead to a decline in quantities produced. After all, under this analysis, increases in prices are necessary to bring demand into line with the reduced supply.

The point is that as supply disruptions ease, supply will be increasing, and that will work to stem and then reverse increases in prices. I have argued here that nominal demand is growing no faster than it did pre-Covid. Without an acceleration in demand growth and with a normalization of supply and supply growth, goods prices must moderate, even decline.

Note that supply-chain disruptions do not have to vanish for the price process to reverse. Disruptions need only begin to ease. Once supply stops declining and merely begins to rebound—again, in the absence of a demand acceleration—goods prices will start to decline.

Now, granted, the pre-Covid spending growth I have cited holds for all goods and services, and it is true that consumer demand shifted from services to goods, to some extent, over the last two years, thanks to the still-restricted nature of many Covid-constrained service industries. So, there was a net increase in the demand for goods, as well as supply-chain restrictions affecting these markets.

However, that shift from services to goods has been in reversal over the last nine months. After an early-2021 spike through March, real consumer spending on goods has been flat to down ever since, even as reopening service sectors saw some increase in demand. Again, goods demand is not at present a source of price pressure for goods. As supply problems ease, goods prices will come down.

Misconception #5: Commodity prices are skyrocketing, a sure sign of inflation.

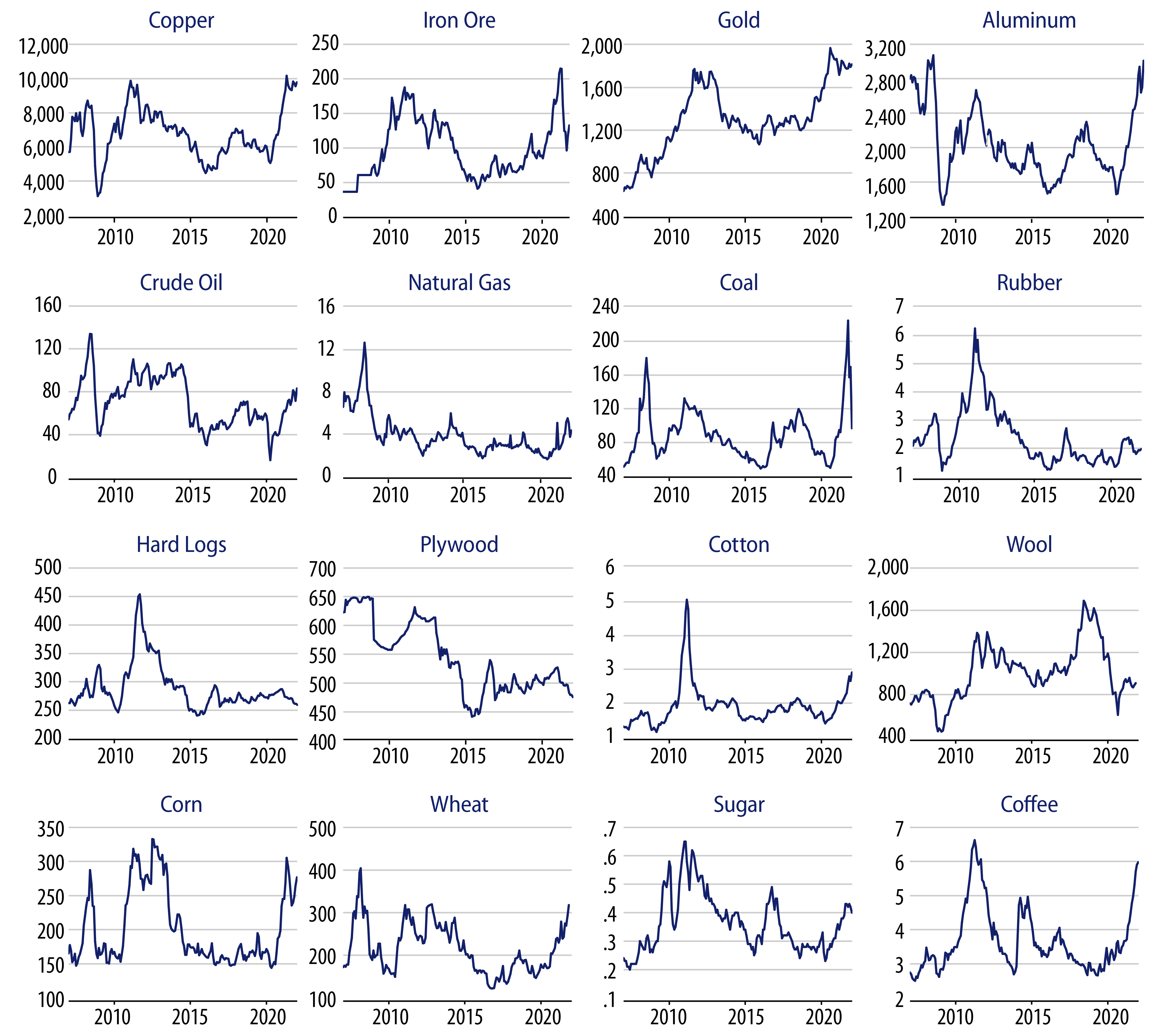

To paraphrase the late Paul Samuelson, commodity prices have predicted nine out of the last zero inflation increases. Commodity prices always rise early in an economic expansion, just as they always decline during recessions. In most of the expansions of the last 40 years, some group of analysts has been predicting rising inflation, and they invariably cite commodity prices as a supporting argument.

Falling commodity prices during recessions do not drive deflations, and rising commodity prices during expansions are not necessarily a sign of inflation. Exhibit 8 plots 16 prominent raw materials prices. Most of them have indeed experienced increases over the last two years. Most of them also saw increases following the end of the GFC. In fact, most of these commodity prices are no higher now than they were 12 years ago at the outset of expansion then. The markets that are seeing higher prices now than in 2010 are the very markets where supply-chain disruptions are at work, a topic I have already addressed.

Rising commodity prices were not associated with higher inflation post-GFC nor in preceding recoveries. I do not see them as a critical inflationary factor presently.

Misconception #6: Fed policy is still too expansive, leading to economic conditions running too hot.

I’ve already dealt with this in some detail and pointed out that aggregate demand has not shown any acceleration from pre-Covid trends, contradicting the contention that Fed policy has caused the economy to run too hot.

I’ll add here some ancillary details. Not only has Fed policy failed to stimulate the economy on net, but the same can also be said of the federal government efforts to stimulate through fiscal policy. As seen in Exhibit 9, each time extraordinary federal aid was provided—by the CARES Act or its successors—personal saving rose by as much as or more than the federal aid provided (and, as explained earlier, that saving largely fed into the money stock).

Notice that not only were the funds saved when they were disbursed, but they continued to be saved in subsequent months. That is, if, say, in August 2020, consumers had spent funds received from the government in April 2020, that would have represented spending in excess of income in August 2020, so that measured saving would have been depressed then. Never since the onset of Covid has there been such an especially low-saving month.

Households’ saving of the temporary aid provided during Covid squares exactly with the Permanent Income Hypothesis, one of the breakthroughs the Nobel Committee cited when it awarded its prize to Milton Friedman in 1977. When consumers are provided a steady stream of new income, they will spend a large portion of that new stream. When they are provided a one-time “grant,” most or all of that windfall will be saved.

We saw such behavior following the Ford tax rebates of 1975, the Bush tax rebates of 2008 and the Obama grants of 2009. We are now seeing the same behavior with respect to the Covid aid provided over the last two years.

Conclusion

I regard the success of the US and other DM economies in finally stemming the inflation of the 1960s and 1970s as the major policy success of the 20th century. It has certainly been a driving factor of our investment strategies for the past 40 years. I never approved of the Fed’s stated intent to raise inflation—even a little—when it voiced such desires a few years ago.

Having said that, I think the various efforts to blame recent price increases on the Fed or other external forces requiring a policy counter-response are lacking in support from both theory and fact. Fed and DM central bank policies in general were unable to stimulate either economic growth or inflation during the post-GFC period. I see nothing different in the Covid era, other than the added complexities introduced by the related economic shutdown. I believe the recent price burst will die out of its own momentum, or lack thereof. I do not think it will be an enduring problem for the fixed-income markets.