The move to replace LIBOR is being driven by a couple of primary factors, and has been a long time coming. In this note, Western Asset Product Specialist Tom McMahon discusses these factors and explains the roots of the international investigation into LIBOR, its possible replacement, why the change matters for fixed-income investors and what we can expect next.

TM: An international investigation into the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) that began in 2012 revealed that many banks had manipulated the rate going back as far as 2003. In July 2017, UK regulators announced that LIBOR would be discontinued by the end of 2021. Even before the disclosure of the LIBOR scandal, US regulators had been researching alternatives for a reference interest rate based on transactions from a robust underlying market. The Federal Reserve (Fed) convened the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) to identify and analyze substitutes. The ARRC considered a number of options including but not limited to fed funds, T-bills and Treasury bonds. In June 2017, the Fed announced its preferred option was the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). On April 3, 2018, the Fed started publishing the rate that regulators hope will be adopted to back US dollar-based derivative contracts and floating-rate obligations.

TM: LIBOR is derived from a daily poll of large banks that guesstimate the cost of borrowing from each other on an unsecured basis. Since interbank borrowing is extremely limited, the rate each bank has offered has been more of a theoretical exercise. Given that the rates submitted were based on a theoretical exercise rather than on actual transactions, there was always a risk of manipulation of the rate whereby banks would report rates advantageous to their current trading position. Unfortunately, this risk became a reality.

TM: SOFR is an overnight rate based on US Treasury (UST) repo transactions. Eligible repo transactions include the triparty general collateral rate collected by the Bank of New York Mellon, the General Collateral Financing (GFC) repo rate from the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) and the bilateral Treasury repo transactions cleared at the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC). The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) pools the data from these three sources and after some minor editing, solves for the median transaction-weighted repo level, which in turn becomes the SOFR rate. Simply put, SOFR is the cost of borrowing cash overnight while posting risk-free assets as collateral. The scale of eligible UST repo transactions applicable to SOFR is massive, averaging over $800 billion per day according to the FRBNY. The FRBNY began daily publishing of the rate on Tuesday April 3, 2018, based on trade data for Monday April 2, 2018.

TM: A repo or repurchase agreement is a transaction whereby cash is exchanged for debt issues to raise short-term capital. A repurchase agreement, from the borrower’s perspective, is a sale of securities for cash with a commitment to buy back the securities on a future date at a predetermined price. A lender, such as a bank, will enter a repo agreement to buy the fixed-income securities from a borrowing counterparty, such as a dealer, with a promise to sell the securities back within a short period of time. At the end of the agreement term, the borrower repays the money plus interest at a repo rate to the lender and takes back the securities.

A repo can be either overnight or a term repo. An overnight repo is an agreement in which the duration of the loan is one day. Term repurchase agreements, on the other hand, can be as long as one year with a majority of term repos having durations of three months or fewer. The financial institution that purchases the securities cannot sell them to another party, unless the seller defaults on its obligation to repurchase the security. The security involved in the transaction acts as collateral for the buyer until the seller can pay the buyer back. In effect, the sale of a security is not considered a real sale, but a collateralized loan that is secured by an asset.

The repo rate is the cost of buying back the securities from the lender. The rate is a simple interest rate that uses an actual/360 calendar, and represents the cost of borrowing in the repo market.

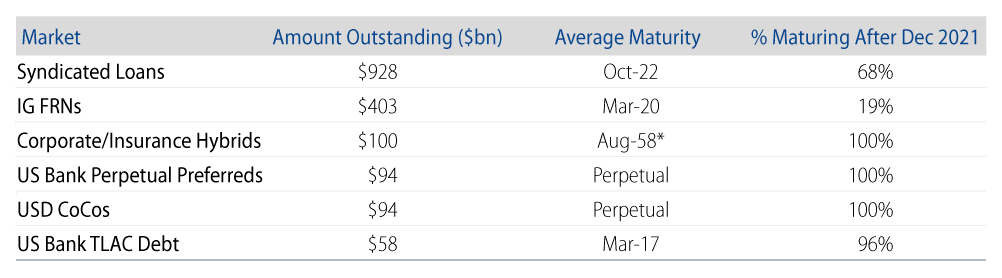

TM: The Fed estimates that there are more than $200 trillion in outstanding derivatives contracts and loans that are based on US LIBOR. The $1.0 trillion bank loan market uses US LIBOR as the reference rate as does $1.1 trillion of the commercial mortgage market and $1.2 trillion of residential mortgage securities. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) reports that $370 trillion of some sort of financial contracts reference IBORs (i.e., interbank offered rates) worldwide. Changing the reference rate on such a large pool of funds across the entire financial market globally is very significant. Specific to the credit markets, Exhibit 1 lists the market value of securities across the spectrum utilizing LIBOR as a reference rate.

Market Value of Securities Utilizing LIBOR as a Reference

*Average maturity date for dated securities, 37%, is perpetual

TM: The FRBNY has begun posting the SOFR on a daily basis. SOFR-linked futures are up and running, though volumes have been light. The ARRC is hopeful that new swaps referencing SOFR will be an available option at the time of execution between counterparties by 1Q20. By the end of 2021 ARRC expects to have in place a term reference rate based on SOFR derivatives. Turning an overnight rate into a term rate is no easy task. However, the combination of the overnight and term Treasury repo market should help move this process along. It remains to be seen what will happen to floating-rate financial obligations that mature after December 2021 and utilize LIBOR as the reference rate. Most of these contracts call for using the most recent posted LIBOR rate that, if followed, would result in these floaters becoming fixed-rate obligations for the remainder of their terms. There are industry working groups looking at standardizing language that would amend the pricing methodology to account for the move from LIBOR to SOFR.

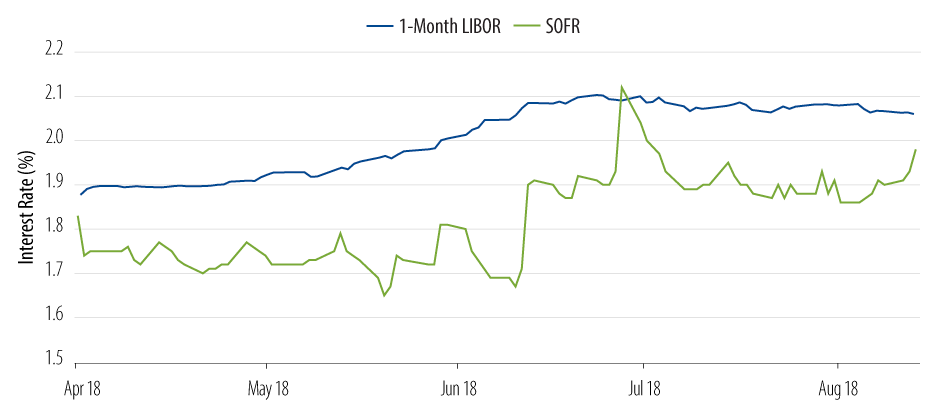

1-Month LIBOR and SOFR

The extent that liquidity in SOFR derivatives develops will go a long way in determining whether or not the market will accept the move to SOFR. A key problem with reliance on an overnight rate is the rising cost of capital that is experienced almost every quarter-end. Overnight borrowing costs typically rise at quarter-end as banks and dealers tend to shrink their securities holdings, in some cases to comply with regulatory requirements. The greater demand for cash tends to drive repo levels higher for a brief period of time. There are other issues as well that make this project a challenge, including the fact that this change from LIBOR to SOFR is not a regulatory requirement. At the end of the day, it will be the market that decides if SOFR is an acceptable replacement of LIBOR.