KEY TAKEAWAYS

- We believe the Covid period will prove to be an exceptional historical outlier, and that the disinflationary headwinds already in place will become even more prominent.

- The arc of the disinflationary process should prove to be long and uneven, and the patience of investors and policymakers will be tested.

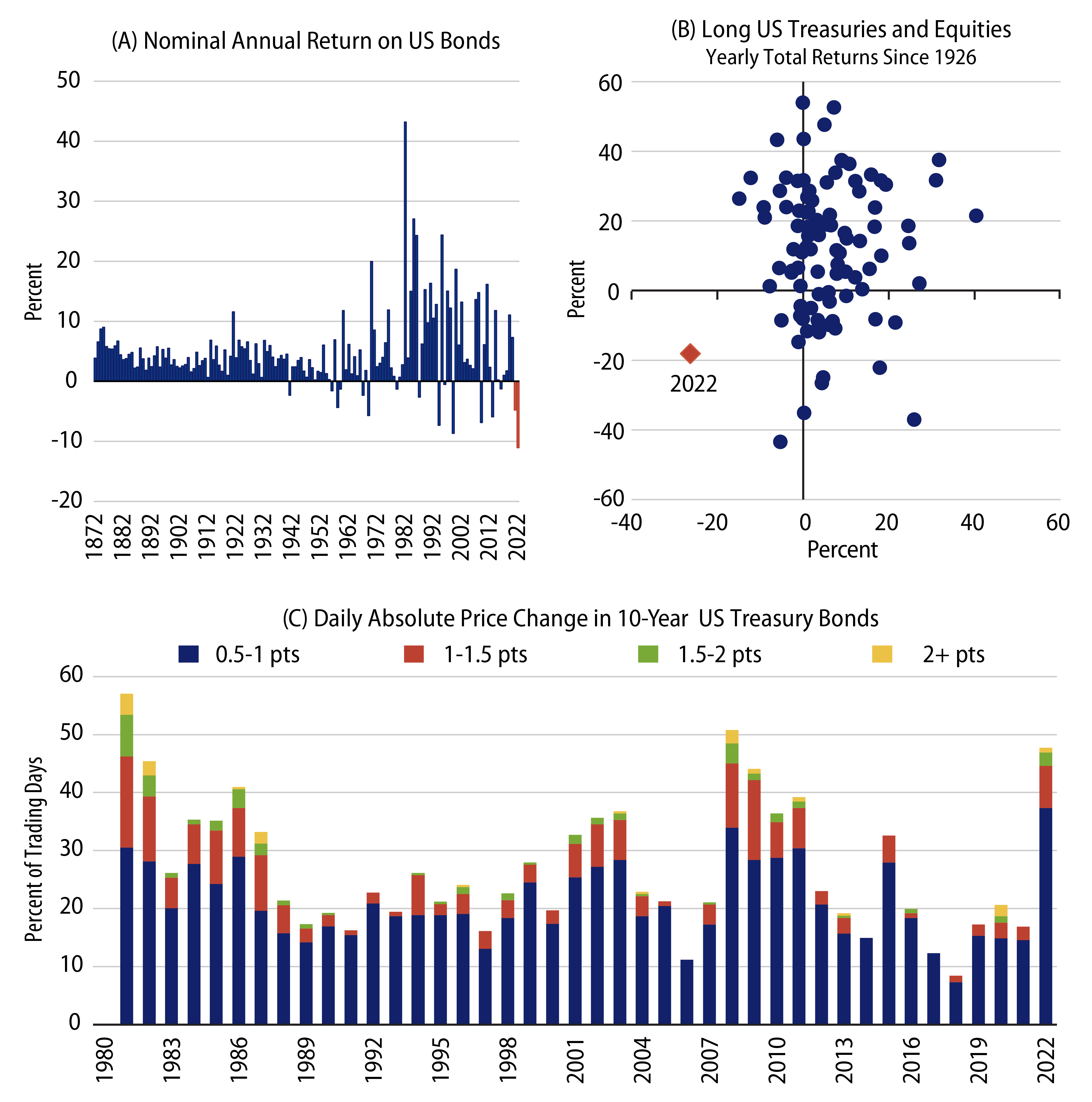

- The enormity of the inflation surge and inflation response led to three rather rare fixed-income attributes in 2022—but none are likely to recur: (1) Total return was the most negative on record, (2) correlations across asset classes became historically distorted and (3) interest-rate volatility was the most elevated it has been in over 40 years.

- Our view is that the process of disinflation combined with the Fed’s zealotry in hiking rates makes the question of the end of the hiking cycle a when rather than an if issue. Taking a bit of a longer view, missing the potential opportunity in search of precise timing is suboptimal.

Monetary policy acts with long and variable lags. This dictum, so often repeated, is almost invariably cast aside by market participants and policymakers in the swirl of rapidly evolving economic data. It’s easy to understand why this is. It is not just the recency bias we all innately possess. Policy levers follow the economic terrain and from necessity, market participants must react to those policy choices.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) is in no way exempt. Fed officials chronically remind listeners about the long and variable lags, then adjust policy every six weeks based on the most recent data. And it has always been thus. The history of the Fed is one of over-easing followed by over-tightening. The Fed’s historical record in economic forecasting is very poor, but it has complete command of short rates, so its policy road map must be followed closely by market participants. And this road map changes quickly as data changes. So the Fed taking a longer-term view based on the “long and variable lags” has always been conspicuous by its absence.

Nevertheless, the dictum holds. Fed policy in 2022 saw the sharpest increase in both short- and long-term interest rates since the Volcker tightening of 1980, and money growth was negative for the first time since the Great Depression. Our position has been that an easing of supply constraints and an abrupt reversal of Fed policy would work to provide gradual but fairly steady progress in easing inflation pressures. In line with this monetary policy regime, growth in nominal spending has decelerated steadily over the past two years. In fact, nominal domestic demand, spending by consumers, businesses and government grew at no faster pace in 4Q22 than was seen in the two years prior to Covid. Without sustained increases in nominal spending, inflation can’t continue, and the progress on that front last year was undeniable. With downward trends in place, and the lagged effects of monetary tightening still working their way through the system, the war on inflation is being won.

As for the inflation prints, the January data are indeed a setback, but that comes after three months of very benign readings. The arc of the disinflationary process should prove to be long and uneven, and the patience of investors and policymakers will be tested. Will the Fed pause and hold as it has explicitly announced? Or will it continue to chase each new data set, only to be forced into the policy pivot it now decries? That is the key question for the market. For with policy rates already in restrictive territory, the possibility of a policy error and subsequent recession increases.

The enormity of the inflation surge and inflation response led to three rather rare fixed-income attributes in 2022—but none are likely to recur (Exhibit 1): (1) Total return was the most negative on record, (2) correlations across asset classes became historically distorted and (3) Interest-rate volatility was the most elevated it has been in over 40 years.

The restoration of yields in broad swathes of the fixed-income markets approaching levels not seen in roughly 15-plus years suggests total returns will be anchored by coupon income, hence limiting potential weakness in total returns. The enormity of the volatility not seen in 40 years is unlikely to recur; last year’s record hiking cycle is not only unlikely to be repeated but is actually coming to a close. Last, the breakdown in correlations, which led to the “death of the 60/40 portfolio” chatter, was based on continually rising combined with outsized central-bank hiking—all driving correlations across asset classes to near one.

The first six weeks of the year saw these correlations diminishing, only to re-emerge with the inflation flare-up and the fear of re-accelerated Fed hikes. But as the year goes on and we work toward the Fed’s endgame, we should see a decline in market volatility and correlations. The benefit of diversified strategies, which depends on lower correlations, should return as the valuable cornerstone of portfolio construction it has always been.

Currently we find value across the breadth of the fixed-income markets. Yields are priced for inflation and default rates which, viewed with more than a six-month lens, are overly pessimistic. Part of this unfortunately reflects the non-negligible risk that the Fed goes too far and induces a recession. This is why the focus on correlations is so important. If the dominant and never-ending risk scenario to fixed-income is always increasing inflation and Fed hiking, then correlations will stay elevated as last year’s storyline will continue to play out. But if recession is the primary risk, duration is the crucial diversifier for spread risk. There has never been a recession without a meaningful fall in interest rates. But even in the absence of recession, a continuation of the disinflation process that Fed Chair Jerome Powell identified publicly in early February would prove beneficial to reducing volatility and restoring correlations.

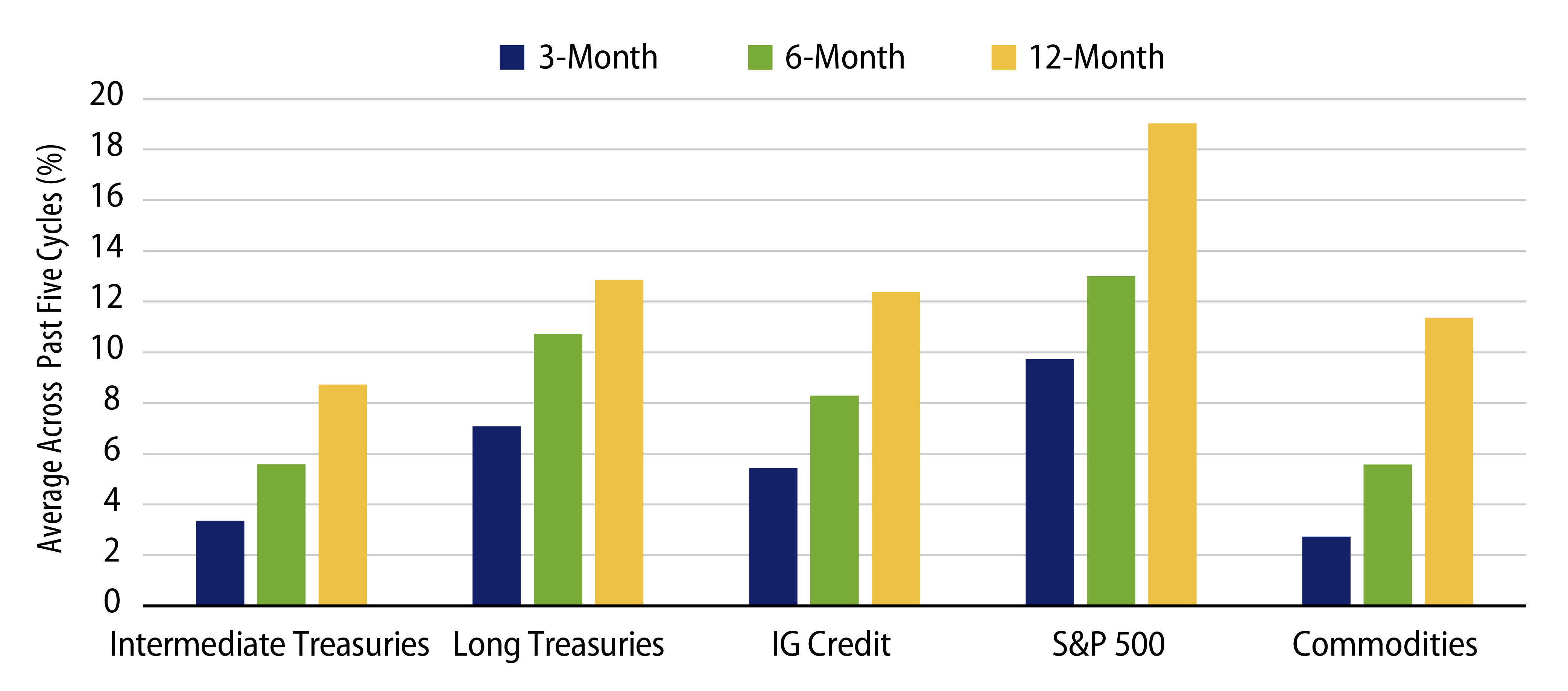

Why are market participants so intent upon identifying when the interest-rate hiking cycle will end? The answer may be seen in Exhibit 2, which displays the total return of the major asset classes following Fed pauses in each of the last five hiking cycles. As can be readily seen, the returns have been exceptional. Our view is that the process of disinflation combined with the Fed’s zealotry in hiking rates makes the question of the end of the hiking cycle a when rather than an if issue. Taking a bit of a longer view, missing the potential opportunity in search of precise timing is suboptimal.

Fixed-income markets provide the income and yield benefits investors have been seeking for well over a decade. Markets are forward-looking. The Covid dislocations have substantially receded. The policy stimulus is behind us. Covid cash stockpiles have come down sharply. Fiscal policy has tightened and a resurgence appears quite unlikely. And monetary policy is now a gale force headwind.

The bear market case for bonds is that the Covid period has completely flipped the script. The chronic shortage of labor and a renewed emphasis on fiscal policy will keep inflation elevated for years to come. We believe the Covid period will prove to be an exceptional historical outlier, and that the disinflationary headwinds already in place will become even more prominent.

Before Covid, we lived in an oversupplied global economy. The need for safe income as longevity issues dominated long-term investment decision making augured very favorably for fixed-income. The biggest bear market in well over 100 years combined with the 180-degree turn in policy has restored that opportunity for investors.