Market Commentary

Life is not always a matter of holding good cards, but sometimes, playing a poor hand well. ~Jack London

Executive Summary

- The divergence of US and global growth has led to broad-based dollar strength, higher US interest rates and accelerating risk premia in spread products outside of the US, particularly in emerging markets.

- Moderating global and US growth levels, while still sturdy, imply an extremely benign inflation backdrop.

- Monetary policy has been tightening for two years and fiscal stimulus is waning. Manufacturing data is decidedly less buoyant, the booming oil patch is likely to pause and housing is headed lower, though admittedly at a modest rate.

- The US-China trade front has introduced tremendous uncertainty in the global economy; however, China’s interest-rate cuts, reserve requirement reductions, targeted fiscal spending increases, individual tax-rate cuts and a renewed emphasis on providing credit to the private sector all suggest that slowing Chinese economic growth will reverse over the course of the next several quarters.

- Our base case on the Brexit resolution is that either a deal close to the present initiative or a “kick the can down the road” agreement is much more likely than a “hard Brexit.”

- We believe that ongoing central bank policy adjustments will help continue the global expansion, and the requisite investment strategy follows from that optimism.

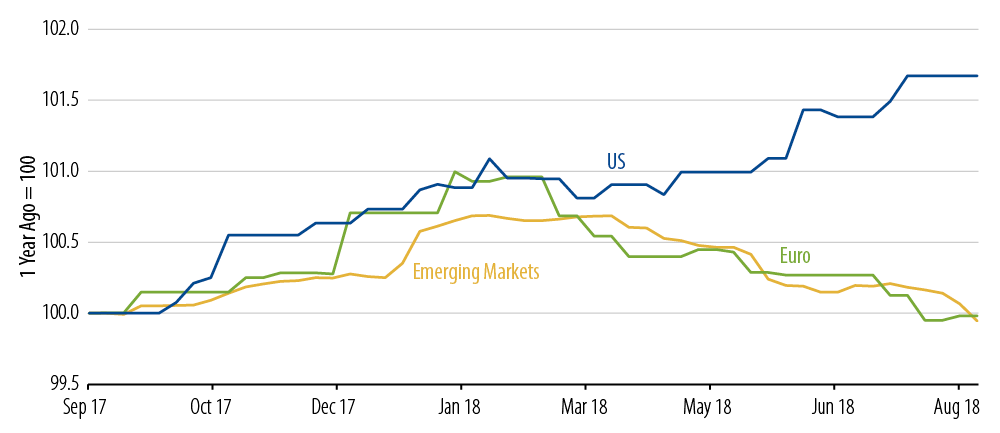

This year’s early expectations for synchronized growth were dashed rather quickly. Instead, we have seen 2018 become the year of the most desynchronized global growth since 1998. The US economy, supercharged with late-cycle stimulus, has gone from strength to strength; the rest of the world, challenged by trade tensions and multiple countries’ idiosyncratic political risks, has gone from weakness to weakness. Exhibit 1 shows the growth revisions to US and non-US growth as the year has progressed; the strength in US growth is in sharp contrast to global downwardly revised expectations. This divergence has led to broad-based dollar strength, higher US interest rates and accelerating risk premia in spread products outside of the US, particularly in emerging markets. Treasury bond market weakness in the US, in contrast to more benign global sovereign markets, has left US rates at multi-decade wides in relation to most other G10 countries.

J.P. Morgan Growth Forecast Revision Indices

All this unfolded before October, when fears of Federal Reserve (Fed) policy errors, ever-escalating trade tensions, Brexit and Italy fears finally led to US spread product weakness as well. Global growth has been softer, and now these multiple downside tail-risks are in full display. How could anyone be even modestly constructive amidst such gloom? What could possibly go right?

Our answer is that quite a lot can go right. Furthermore, a lot has already begun going right. Let’s start with the most important bit: the fundamental underlying economic outlook. Moderating global and US growth levels, while still sturdy, imply an extremely benign inflation backdrop. The tightening of monetary conditions combined with waning effects of fiscal policy in the US contrasted with the re-introduction of both monetary and fiscal stimulus in China augur well for the resynchronization of global growth. All this should be positive for global risk markets. But will the tail-risks that are so ominous upset the apple cart? This is where caution needs to be exercised, but here too there are encouraging signs.

The Fed under Jerome Powell started the year by upwardly revising its expected path of Fed policy rates based on two considerations: greater fiscal thrust and stronger global growth. Fiscal policy effects are now set to wane, and global growth has downshifted. In August at Jackson Hole, Chair Powell explained the importance of acknowledging the uncertainties and challenges in strictly following Fed economic models based on myriad assumptions that have historically often been subject to meaningful revision. The humility of this call—understanding the difficulty and importance of forecast error and the implicit conclusion that monetary policy tightening would therefore be more cautious—was well received by the market. Fed policy should tighten as inflation rises, but anticipatory tightening by the Fed based on its models and assumptions has often gone wrong. Powell’s apparent understanding of this crucial difference gave investors confidence that a policy mistake in the current debt-burdened world would be less likely.

Unfortunately, Powell’s subsequent remark in response to a reporter’s question on interest rates—that while he did not know precisely where the neutral interest rate laid, he knew it was a long way from here (higher)—undid this line of reasoning. Powell’s confidence in the underlying strength and sustainability of the economy and the Fed’s forward forecast of future inflation was clearly on display with several truly incautious remarks by a Fed Chair. The US equity and spread product markets have not seen the light of day ever since Powell’s reversion to Fed orthodoxy with his October 3 comment.

More recently, however, the Fed has reverted back to its “moving cautiously” rhetoric. Powell has talked about moving slowly in a dark room, while Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida added “with shoes off” to the analogy. More importantly, a renewed focus on contained inflation, risk management and a lack of certainty about equilibrium or neutral rates suggests a more dovish direction. Furthermore, Powell just declared that the Fed is very near the neutral range (thought to be 2.5%-3.5%). Is this a true change of heart? Belated recognition that its economic forecast was too optimistic? Or a simple response to the quick tightening of financial conditions? We’re optimistic the new tone will prove helpful, but it’s too soon to tell. More importantly, monetary policy has been tightening for two years and fiscal stimulus is waning. Manufacturing data is decidedly less buoyant, the booming oil patch is likely to pause and housing is headed lower, though admittedly at a modest rate. We think as the Fed comes to face more seriously a moderating growth and inflation outlook, a pause will be both signaled and warranted.

The US-China trade front has introduced tremendous uncertainty in the global economy. Risk premia have risen substantially, particularly in the emerging markets. While there is always hope that some definitive resolution in trade can be reached between the two countries, the more salient point now is the reversal of Chinese economic policy that the dispute has engendered. Gone is China’s deleveraging campaign of earlier this year. Interest-rate cuts, reserve requirement reductions, targeted fiscal spending increases, individual tax-rate cuts and a renewed emphasis on providing credit to the private sector all suggest that slowing Chinese economic growth will reverse over the course of the next several quarters.

In Europe, the modest slowdown in growth is additionally clouded by concerns over Italy and Brexit. Neither of these tail-risks can be ignored. Indeed that is why monetary policy in the UK and Europe remains so extraordinarily accommodative. But while a thorough review of each of these issues is beyond the scope of this note, we think there is reason to be optimistic that the worst-case scenarios discounted in current market prices will be avoided. Our view is that monetary policy continues to be highly focused on underwriting the expansion. We think the Italy-EU dispute will continue to garner headlines but the differences between the two sides are hardly monumental. Our base case on the Brexit resolution is that either a deal close to the present initiative or a “kick the can down the road” agreement is much more likely than a “hard Brexit.”

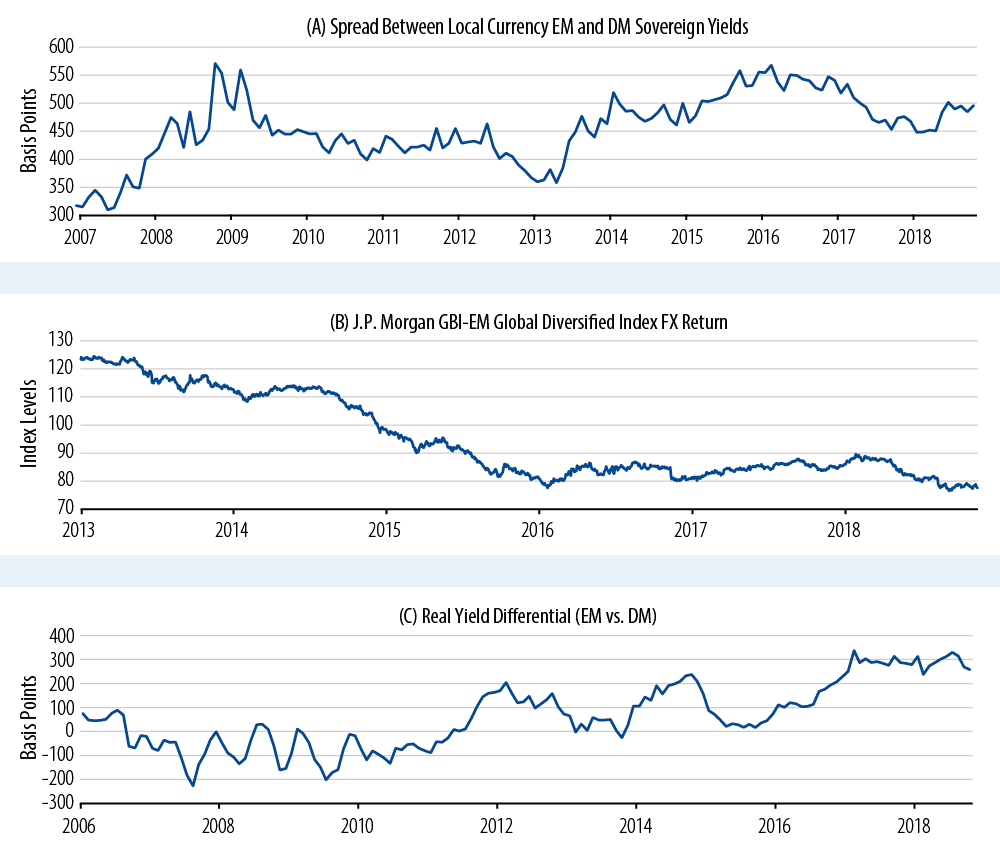

Where does this leave emerging markets? A global recession brought on by a number of these enumerated risks would be highly detrimental. This is why the asset class has suffered so greatly. And the path that has to be traversed through this field of risks would seem to be too nuanced to be worth the effort. But that’s precisely why this is the most undervalued asset class (Exhibit 2). Yield spreads between emerging market debt and developed market debt are near 2008 and 2016 wides. Currency levels are 35% lower than just five years ago. The real yield of emerging market debt is at a 15-year wide versus the real yield of developed market debt. Our view is that this asset class would be the biggest beneficiary of any attenuation of these global risks.

Emerging Markets (EM), the Most Undervalued Asset Class

(B) Source: J.P. Morgan, Bloomberg. As of 12 Nov 18

(C) Source: Bloomberg, HSBC. As of 31 Oct 18

The overarching principle of policymakers since the financial crisis has been to maintain the global recovery. The false hope at the beginning of the year that policy accommodation could be withdrawn in a reasonably benign way has been replaced by the unfortunate reality that continued assistance remains necessary. In Europe and Japan, the extraordinary monetary stimulus remains in force. China is now moving to increase policy stimulus. Even in the US, risk management will remain the driving policy imperative. Our belief is that these policy adjustments will help continue the global expansion, and the requisite investment strategy follows from that optimism.