KEY TAKEAWAYS

- CLOs allow investors to diversify their fixed-income portfolios, and may provide an attractive rate of return compared to other asset classes with comparably rated investments.

- Each CLO has nuanced differences but there are standard provisions that are embedded in every transaction.

- Key covenants found in every CLO are designed to protect a debt tranche investor’s investment.

- Western Asset believes that CLOs are an attractive investment option for qualified investors.

What Is a CLO?

A collateralized loan obligation (CLO) is a portfolio of bank loans that is securitized and actively managed like an investment fund. The vehicle issues debt tranches (liabilities) in the securitization market with varying degrees of risk and return that are tailored to the investment objectives of a vast investor base that span across banks, insurance companies and asset managers. The proceeds raised are used to purchase a portfolio of collateral (assets) which are then actively managed over a defined investment period and within the confines of a specific set of guidelines. Any residual value between the assets and liabilities represents equity interest, which is an ownership stake in the CLO and acts as the first-loss position. The equity tranche is usually retained by a combination of the manager and third-party investors. Debt tranches are issued with ratings normally ranging from AAA to BB. These ratings are dependent on the underlying collateral composition as well as the amount of subordination by which each tranche is supported. Cash flows received from the collateral are paid sequentially to the debt investors from the top down, while any losses are allocated in reverse order from the bottom up. Exhibit 1 shows a typical CLO capital structure.

There are two primary types of CLO structures: balance sheet and arbitrage. Balance sheet CLOs are typically securitizations created by the financial institution that originated the loans (predominantly middle market sized) and that in turn manage the structure and use the securitization market as a means of financing its current loan holdings. Arbitrage CLOs are securitizations with underlying assets comprised of broadly syndicated loans and represent approximately 90% of the CLO market. They are referred to as “arbitrage” because they look to generate excess spread between the income received on the assets (coupons on the loans) and the cost of the liabilities (interest on the debt tranches). The excess spread is typically paid quarterly to the equity holders. Going forward in this paper, all information and commentary with regard to CLOs will refer to arbitrage CLOs that are collateralized by broadly syndicated loans (BSL).

CLO Collateral

BSLs are loans made to established businesses—those that generate annual EBITDA > $50 million—and issuance size exceeds $250 million. There are over 1,500 issuers in the BSL market, oftentimes from recognizable household names such as Dell, Burger King or the Four Seasons to name a few. These issuing companies span over 40 industries. CLOs are required to be broadly diversified across these industries with limited issuer and industry concentrations. Collectively, the loans that make up a CLO’s collateral earn a weighted average rating factor (WARF) and a weighted average spread (WAS). WARFs typically range from 2,000 to 3,000, with a lower numeric score indicating a portfolio with a higher quality bias; alternatively, a higher WARF typically favors a lower quality bias. The WAS provides the starting point as to the potential excess spread available to equity investors when considered against the average financing cost of all the debt tranches.

The Life Cycle of a CLO

There are three distinct periods over a CLO’s life cycle.

- Warehouse – During this period the manager begins to buy loans and ramp up the CLO portfolio. The capital to do so can be sourced from a combination of the manager, third-party investors and the underwriter. The equity generally represents 10% of a CLO’s capital structure. The underwriters will typically provide leverage on the amount the equity investors post between a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio. For example, if a manager deposits $10 million in the warehouse, they are allowed to buy $40 to $50 million in loans. This process repeats itself until the manager feels they are sufficiently ramped. “Sufficiently ramped” is a subjective determination depending on the manager and market conditions, but at a minimum it is the point at which there’s a high likelihood that the various tranches of the CLO can be successfully placed with end investors in the securitization market. On average, most CLOs will be ramped between 40% and 50% before pricing the CLO transaction. On occasion, a manager may choose to issue a CLO when there are no assets ramped in a warehouse. These transactions are commonly referred to as “print and sprint” CLOs. In these cases, the manager and underwriter would sell the CLO’s liabilities first and then the manager would proceed to buy assets in the market immediately thereafter.

- Reinvestment – When the CLO debt tranches are priced, placed and settled, the proceeds of the sale of the tranches pay off the warehouse and the balance is used to continue ramping the portfolio. At this point the CLO is considered “live” and the reinvestment period begins. Reinvestment refers to that period in the life of a CLO when the manager can actively reinvest proceeds from portfolio sales, paydowns, amortizations and maturities. The CLO portfolio is actively traded to accurately reflect the manager’s views on value and to ensure it remains in compliance with the covenanted requirements. The reinvestment period typically is for a term of three to five years.

- Amortization – At the expiration of the reinvestment period the manager’s reinvestment capabilities are limited to a new set of “post-reinvestment rules” resulting in a portion of proceeds from sales, paydowns, amortizations and maturities being allocated toward returning capital to debt holders sequentially according to tranche seniority. The AAA rated tranche amortizes first, then the AAs next and so on. The majority equity holder(s) have the option to call, refinance or reset the CLO after the non-call period expires (typically two years). If none of these events occur prior to the start of the amortization period, the CLO will start to de-lever and its average cost of debt will begin to rise and erode the embedded excess spread. To the extent the arbitrage is no longer economical, the majority equity holders will likely call the CLO. When this occurs the debt tranches are paid off according to seniority and any residual monies are distributed to the equity holders. There is also a mandatory clean-up call when a CLO’s debt liabilities fall below a prescribed level, typically 10% of the debt tranche par value at the time of original issuance.

Growth of the CLO Asset Class

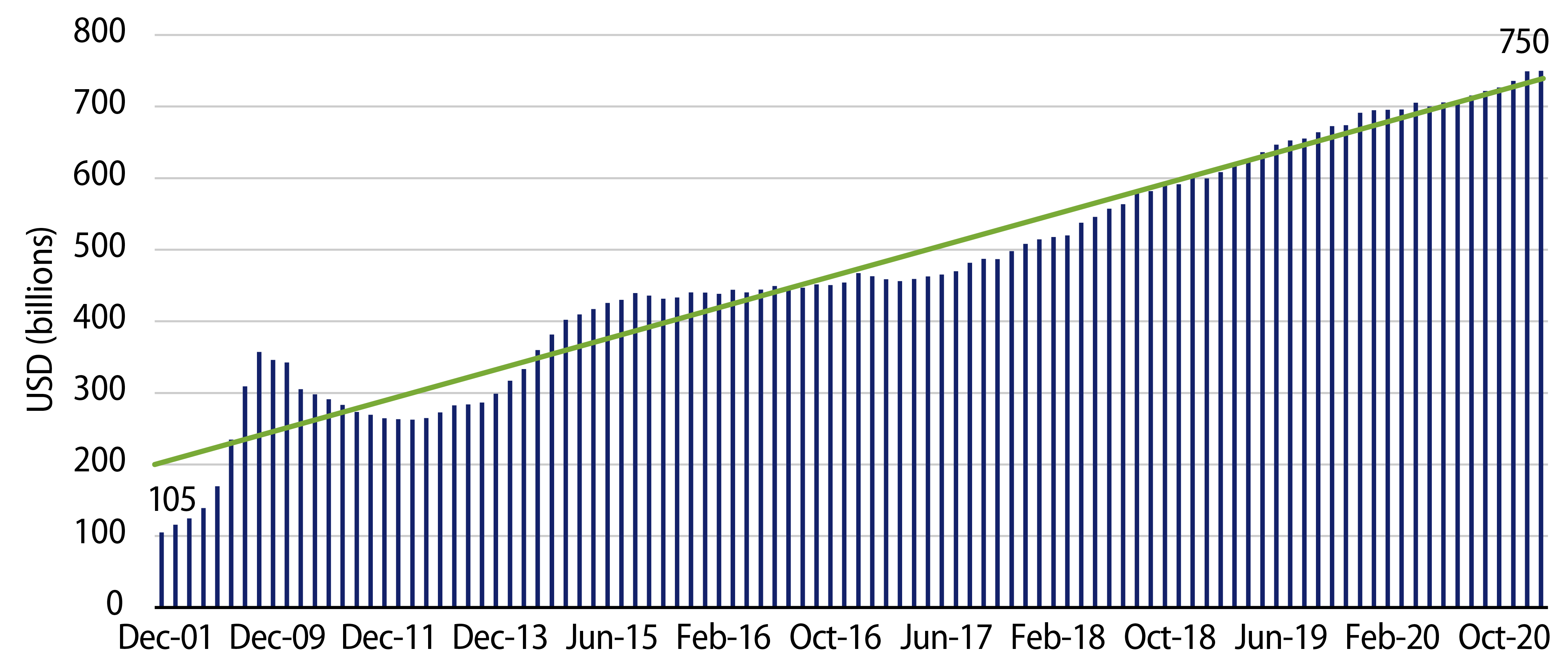

The underlying collateral of the CLO market, bank loans, has grown to over $1.2 trillion and remains an important source of capital for US corporations to fund their operations. As of today, CLO vehicles own approximately 60% of the $1.2 trillion bank loan market with the balance being owned by mutual funds and institutional entities. Much of the growth in the CLO market can be attributed to a continuously expanding investor base consisting of large banks, both foreign and domestic, insurance companies and asset managers that are drawn to CLOs due to their diversification benefits, strong historical performance and attractive relative value.

Standard CLO Covenants

Covenant analysis provides insight as to the leeway a manager has in terms of altering the composition of a portfolio over the life of a CLO. Investors prefer tighter covenants while managers prefer more flexibility. Credit rating agencies have requirements to attain the desired rating at the time of issuance by tranche, and to the extent a manager must remain within those covenants, they provide investors with a level of comfort such that the risk profile and integrity of a portfolio should remain largely in line with what investors were shown in the initial marketing stage of the CLO. Following are examples of some key covenants found in every CLO, which collectively are designed to protect a debt tranche investor’s investment:

- Maximum allowable debt in second liens

- Limit on purchasing smaller-sized loan facilities

- Limited unsecured loan and bond allocation

- Limit on industry concentration

- Maximum allowed in CCC issues

- Minimum overcollateralization requirement

- Limit on distressed exchanges

- Limit on purchase price of assets

- Maximum amount allowable in covenant-lite loans

Though covenant features are fairly homogeneous, structurally CLOs can vary meaningfully from one to the next. Each CLO has nuanced differences but there are standard provisions that define the structure of every CLO transaction, including:

- A non-call period, typically one to two years. During the non-call period the manager cannot call or refinance any of the debt tranches.

- A stated reinvestment period, typically three to five years. The reinvestment period is that time during which the manager is able to reinvest bank loan sale proceeds, paydowns, amortizations and maturities back into the loan market.

- Management fees, typically 40 to 50 basis points (bps), which are usually split into senior (“top of waterfall”) and subordinate (“bottom of waterfall”) fees to best align the interests between debt and equity investors. Most transactions also include an incentive fee of 20% at an equity hurdle rate of 10% to 12%.

- A stated legal final maturity, typically 12 to 13 years.

In practice, CLOs rarely make it to the stated legal final maturity due in large part to the amortization of the higher-rated/lower-cost debt tranches. Amortization of these tranches begins once the reinvestment period ends. The AAA tranche is the first to amortize and is typically fully paid off by years six or seven. As the higher-rated debt tranches are retired, the excess spread (i.e., the difference between the spread earned on the assets and the average cost of the debt tranches) compresses. At a certain point, which is typically well inside of 12 years, it becomes uneconomical for the remaining debt tranches to remain outstanding and the equity investors can exercise their rights to either call the debt tranches and collapse the deal or, if economical, reset the coupons on the debt tranches and extend the life of the transaction. Resets typically result in the extension of the non-call and reinvestment periods. In most cases, CLOs are either refinanced or reset at the end of their non-call period before any amortization occurs.

Historical Performance of CLOs

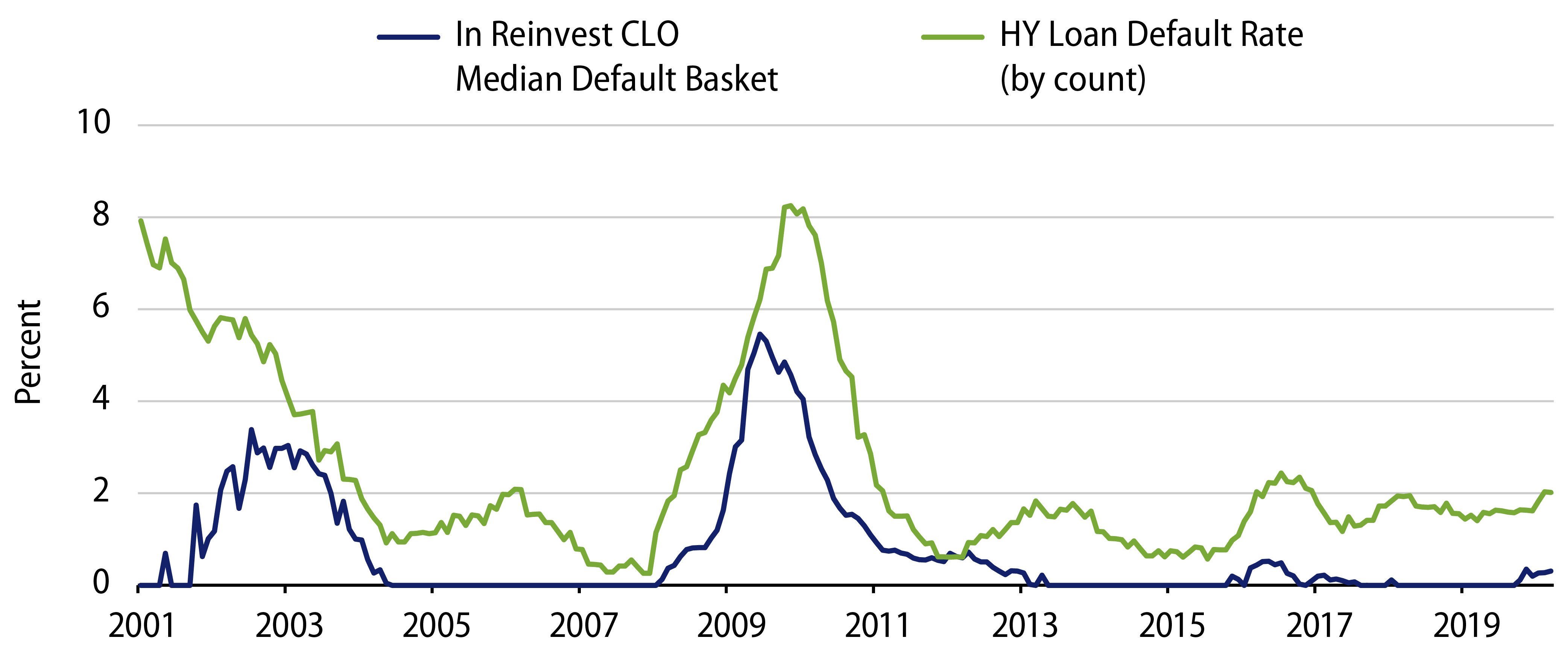

While the market has experienced elevated defaults on a number of occasions over the past 25 years, no AAA to A rated CLO debt tranche has ever suffered any impairment dating back to the creation of CLO structures in the early 1990s. CLOs are advantaged by required diversification measures as well as an extensive list of covenants embedded within the structures that are designed to protect debt investors across every rating category.

CLOs exhibit a higher quality bias due to the tug-of-war nature between debt and equity investors. Managers must prove to be capital structure agnostic and managing for the benefit of the entire investor base. As a result, most CLO managers are incentivized to construct a portfolio that’s skewed to higher quality than the average underlying loan market in order to appease investors as well as to ensure they can meet the deal’s specified quality metrics, coverage ratios and concentration limitations bestowed upon them by the rating agencies and debt investors. Avoidance of defaults/losses, new-issue allocations and active management are keys to delivering the marketed returns to equity investors. This dynamic has resulted in the CLO market historically exhibiting a materially lower default rate versus the broader loan market.

CLO Evolution

The securitization market was incepted in the late 1970s with the packaging of home loans to create the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) asset class. By the late-1980s, securitizations were commonplace and in the early-1990s the first CLO was issued. Prior to the early-‘90s the bank loan market was a closed market owned and traded exclusively among the banking community. An increase in the capital charge for banks to hold these loans on their books ultimately lead to the development of the CLO structure, which would be used to remove loans off of bank balance sheets.

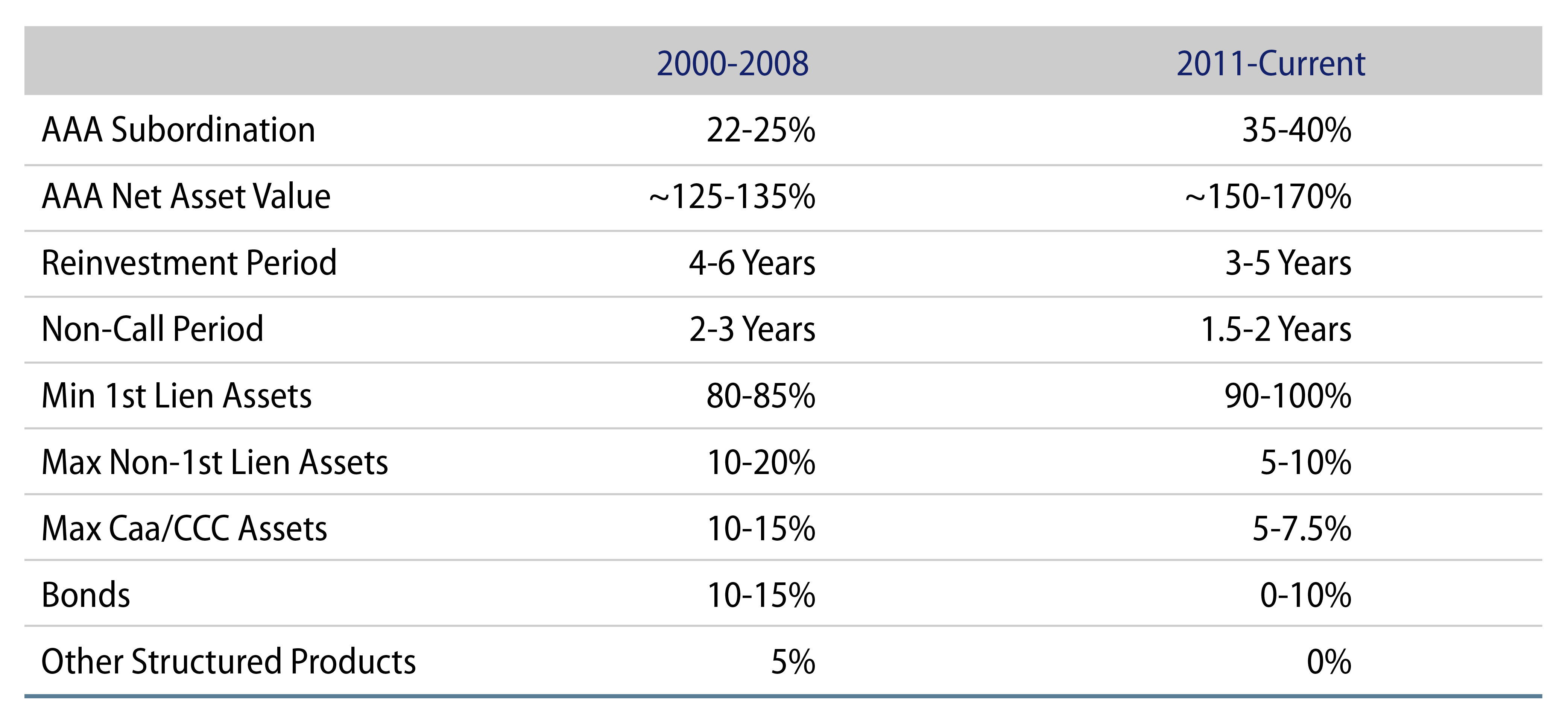

Despite CLOs proving to be one of the best performing asset classes in fixed-income, rating agencies continue to take a conservative approach to rating CLOs which has been a welcomed benefit to investors resulting in meaningful enhancements to the CLO structure and documents. Following are some of the key differences between CLOs issued during the 2000s versus today.

Today’s CLO structures have greater subordination for the debt tranches providing a larger degree of support in the event of elevated distress in the markets. The newer structures also limit investment in unsecured loans and bonds, which historically have lower recovery rates due to their lower priority position within a company’s capital structure. Investment in CCC rated and second-lien loans are also more limited. These enhancements to the CLO structure have resulted in higher quality portfolios and more credit enhancement for the CLO debt investor base than earlier structures, which means it would take an event significantly more stressing than what’s been experienced historically to impair any CLO debt tranches.

Investment Merits of CLOs

CLOs may be able to provide positive benefits to investors as a component of their fixed-income portfolios. Western Asset believes CLOs offer many attractive features that may not be found in other investments, including:

- No Rate Risk: CLO tranches are floating-rate assets.

- Diversification: The typical CLO holds an average of 200 issuers across approximately 40 industries. CLOs have historically exhibited low correlations versus equities and US Treasuries.

- Defined Investment Guidelines: Limits are in place for CCC rated issues, second liens and unsecured bonds. Concentration limits and overcollateralization requirements are also beneficial to investors.

- Transparency: CLOs have quarterly reporting requirements, including full collateral listing with individual loan details and marks.

- Compelling Value: CLOs offer strong relative value compared with other asset classes and comparably rated investments with extensive sponsorship from large US banks, insurance companies and asset managers.

- Proven Track Record: CLOs have never experienced an impairment in any tranche rated A and higher, and impairments for BBB and lower rated tranches have been much lower than that experienced in the broader and similarly rated credit markets.

- Large Primary and Secondary Market: CLOs benefit from high daily trading volumes, liquidity and an expanding investor base.