KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The key risk measure for DB plans is tracking error of asset returns against liability returns, not portfolio return volatility.

- So, while diversification across assets is a great way to reduce the asset return volatility, it will increase tracking error against liabilities if the assets being diversified into are less highly correlated—or even negatively correlated with—the liabilities.

- Negative correlation among assets is desirable in total-return portfolios. Positive correlation between assets and liabilities is desirable for DB pension plans.

- Offshore equity indices are often negatively correlated with American DB pension liabilities.

The Holy Grail of Diversification

Investors are taught the virtues of diversification during their first undergraduate course in finance and onward. The habit often carries over to defined benefit (DB) pension management, then to liability-driven investing (LDI).

However, as we always emphasize, managing assets to match or beat pension liabilities is a fundamentally different proposition from managing to a total-return mandate. And it so happens that the quest for diversification—as it is commonly practiced—can sometimes be counterproductive in pension management. Here, we make this point both concretely and simply.

Yes, diversifying a portfolio by investing across different assets will almost always reduce portfolio return volatility. However, for a DB pension plan, the relevant measure of risk is not the volatility of portfolio returns, but rather the extent to which portfolio returns vary versus “returns” on pension liabilities, aka tracking error. And if a plan were to diversify by investing in assets that are negatively correlated with liability returns, said diversification would actually increase tracking error, not reduce it.

Yes, such diversification would reduce the volatility of the portfolio’s return. However, again, by making portfolio returns vary less in line with liability returns, that diversification will increase risk for the plan.

The statements in the previous paragraph may have caught your eye. Yes, we said that it is a bad thing—or, at least, a risky thing—for returns on an asset to be negatively correlated with liability returns. In standard diversification analyses (concerning total-return investing), negative correlation among assets is desirable. Investing in two assets that are negatively correlated—both with presumably positive expected returns—is a fantastic way to reduce the volatility of returns. This is the gold standard for total-return investing.

However, again, the object in pension management is not necessarily to reduce the volatility of portfolio returns, but rather to make fluctuations in portfolio return move in concert with—that is, be positively correlated with—those for liability returns. In short, for total-return portfolios, negative correlation among assets is desirable. In DB pension management, positive correlation between assets and liabilities is desirable.

This difference does not stand financial theory on its head, but rather applies the concepts and tools of finance theory to metrics relevant to a DB plan. The resulting dicta are somewhat different.

This does not mean that a DB pension should never invest in assets that are negatively correlated with liabilities. It only means that the plan should recognize that such investments are possibly much riskier than their return volatility—or beta—might suggest. Such investments should be made only if their potential returns justify their increased risk.

Remember, the standard beta for assets measures not their own riskiness, but how much investment in them contributes to the risk of the aggregate market portfolio. In the same spirit, for DB plans, investments that are negatively correlated with DB liabilities should have their riskiness evaluated based on how much they add to plan tracking error. Here, again, we have not abrogated the basic rules of finance, but merely adjusted them to the specific issue at hand, and the specifics of reducing pension risk are fundamentally different from those of reducing return volatility.

Negative Correlation with Liabilities?

The prime examples of assets negatively correlated with US DB pension liabilities are offshore—or non-US—equities. Our analysis typically finds that offshore equity indices such as EMBI, World or ACWI are negatively correlated with US DB pension liabilities. That is because non-US equity prices have tended to decline when US bond prices are rising, and vice versa.

Because non-US equities are usually negatively correlated with US DB pension liabilities, “diversifying” into them will typically increase the tracking error or riskiness of a US DB pension plan substantially. US equities tend to have zero, or only slightly negative, correlation with US DB liabilities, while the negative correlation is much higher for non-US equities.

Consequently, non-US equities are much “riskier” for an American plan than US equities, and if an allocation to offshore equities is made purely for reasons of diversification, that strategy is unlikely to produce the desired results. Yet, our impression is that American plans indeed typically invest in offshore equities as a “diversification.”

Another example that has surfaced lately is the use of private credit to diversify DB portfolios. We’ll state at the outset that we think private credit is an attractive investment vehicle offered to clients as a way of enhancing returns. However, DB plan managers should be cautious if they think of private credit primarily as a way of diversifying their allocation.

The available data on private credit returns are very short-lived and sketchy enough that it is hard to determine just how they correlate with DB liabilities. However, our understanding is that one of the perceived advantages of private credit is that it is not regularly marked to market, so that its reported returns have very low volatility.

Yet, DB liabilities are regularly marked to market, with actuaries using market data on high-grade corporate bond yields. A plan can reduce tracking error by investing in assets that fluctuate in line with—and are highly positively correlated with—plan liabilities. It is hard to see how this can be accomplished by investing in assets that are evaluated only periodically—and possibly not strictly in line with fixed-income market pricing.

Just a Little Math

We can analytically demonstrate the verbal points made earlier as follows. The basic laws of probability and statistics provide the following formulae for volatility when two random variables, X and Y, are involved. First, when the variables add to each other, as in portfolio returns, the volatility of X+Y can be seen to be:

where VOL() is the volatility of a series, and CORR( , ) is the correlation coefficient between two variables. The first term on the right side says that the higher the volatilities of X and Y, the higher the volatility of their combination (sum). According to the second term, if the two series are perfectively positively correlated, CORR(X,Y) = 1, then NO offset of their individual volatilities occurs. However, as that correlation declines below +1, the term in the brackets, [1-CORR(X,Y)], becomes positive and subtracts from overall volatility, reaching an extreme when the two variables are perfectly negatively correlated: CORR(X,Y) = -1.

When we are dealing with the difference between X and Y, X-Y, the situation is vastly different.

As per this formula, it is not the absolute volatilities of X and Y that matter, but rather their difference. If the volatilities of X and Y were identical, the first term on the right side would be at its minimum, zero. Similarly, the second term says that when X and Y are perfectly and positively correlated, that term is at its minimum, zero. The optimal hedge of X would be a Y that is perfectly positively correlated with X and that has an identical level of volatility. In contrast, the less positively correlated X and Y, the larger the last term on the right. The worst hedge of X would be a Y that is perfectly negatively correlated with X and that had vastly different volatility (either much higher or much lower volatility would be equally bad).

When assets are combined within a portfolio, volatility or risk is reduced by finding assets with low volatility and low or negative correlation with each other. When assets are targeted to match liabilities—such as with LDI—risk is reduced by finding assets with much the same volatility as the liabilities, and with as high a positive correlation with the liabilities as is possible. Standard “diversification” tactics involve investing in a range of assets that are as lowly correlated—or as negatively correlated—with each other as possible. Reflexive following of such a tactic by a DB pension plan could be quite counterproductive.

In the Real World

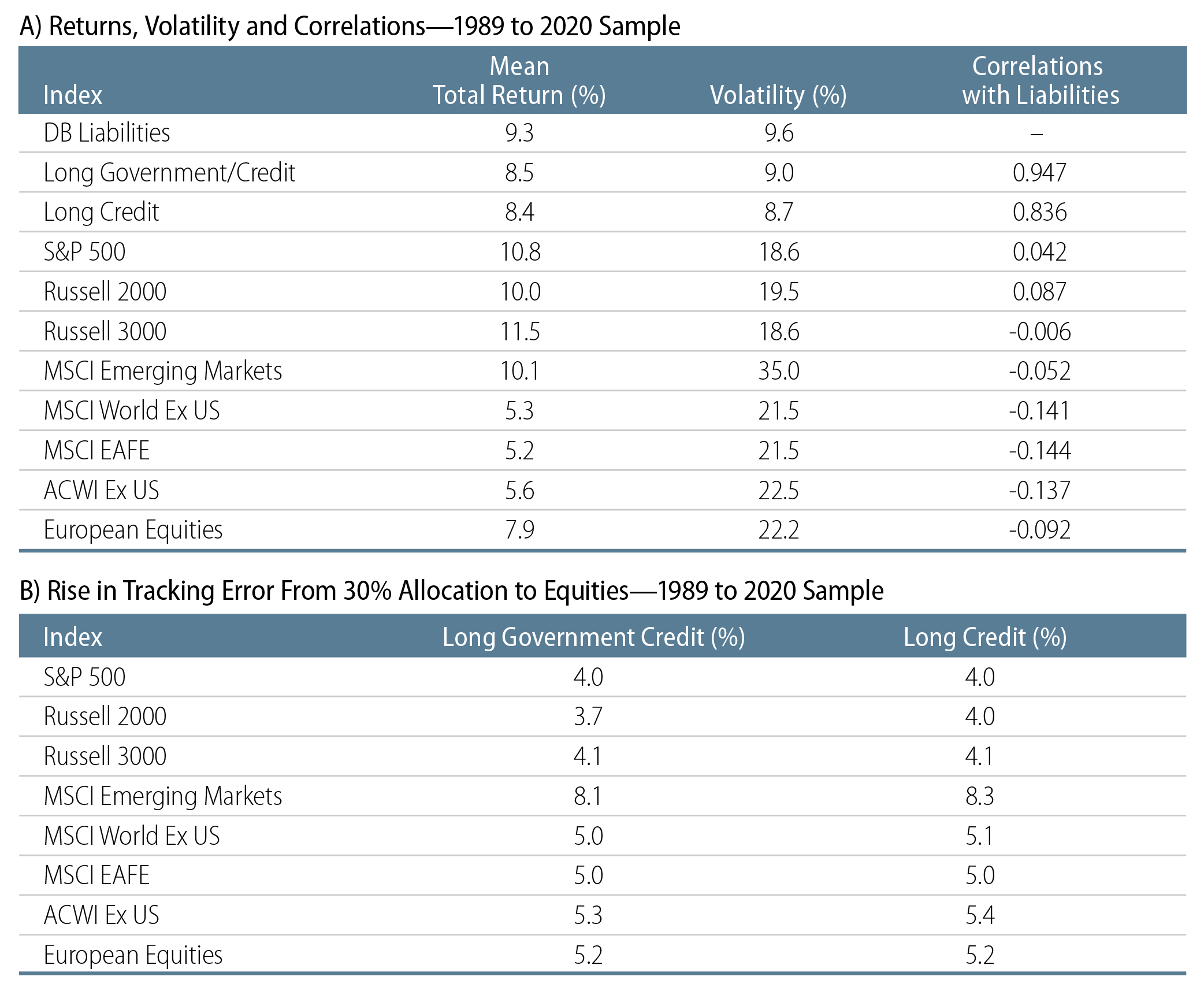

Some real-world data might make these points more concrete. Consider a DB plan whose liabilities had a duration of 12.7 years as of 31 Dec 24, which is about average for an open DB plan. As you can see in Exhibit 1A, foreign equities did indeed generally show negative correlation with these liabilities over the represented 1989-2020 sample period. US equities generally featured very low, positive correlation with DB liabilities. The Russell 3000 had a very slight negative correlation, much less than that for non-US equities.

If these liabilities were hedged by 100% allocations to either long government/credit (long G/C) or long credit, the tracking error against the liabilities would have been 3.4% and 5.8%, respectively, over the 1989-2020 sample. How much would tracking error rise with a 30% allocation to various equity indices (reducing the fixed-income allocation to 70%)?

As shown in Exhibit 1B, allocating 30% of the assets to US equities would have raised the tracking error by approximately 400 basis points (bps) annually, depending on the chosen equity index, irrespective of the fixed-income investment strategy. Investing in non-US, developed market (DM) equities—rather than US equities—would have resulted in an additional 500 bps, 100 bps more than the incremental risk accruing from US equities. Investing in emerging market (EM) equities would have resulted in an even larger increase in tracking error.

While an extra 100 bps to 140 bps in tracking error may seem negligible, this allocation is supposed to be a diversifier and is only a 30% allocation. What returns would make such a shift worthwhile?

Let’s take a 50% information ratio as a reasonable target for investment changes, that is, every additional 100 bps of tracking error would be worthwhile if it afforded an extra 50 bps of expected return. In order for a 30% allocation to non-US equities to be worth the extra 100 bps to 140 bps of tracking error over that from US equities, the offshore equities would have to provide an expected return 167 bps to 233 bps higher than US equities (30% * 166 bps = 50 bps and 30% * 233 bps = 70 bps).

However, as Exhibit 1A shows, non-US equities uniformly underperformed US equities over this sample period. Future market prospects for non-US equities might be more attractive, but the question remains as to whether the extra prospective returns justify the extra risk. Again, any supposed benefits from diversification alone are likely illusory.

For that matter, consider US equities themselves. With a 30% allocation to US equities raising tracking error by 400 bps relative to 100% fixed-income, equities would have to offer a prospective “equity premium” of more than 650 bps per year over long bonds to be worth the extra risk. In fact, the equity premium over this sample period was closer to 200-300 bps.

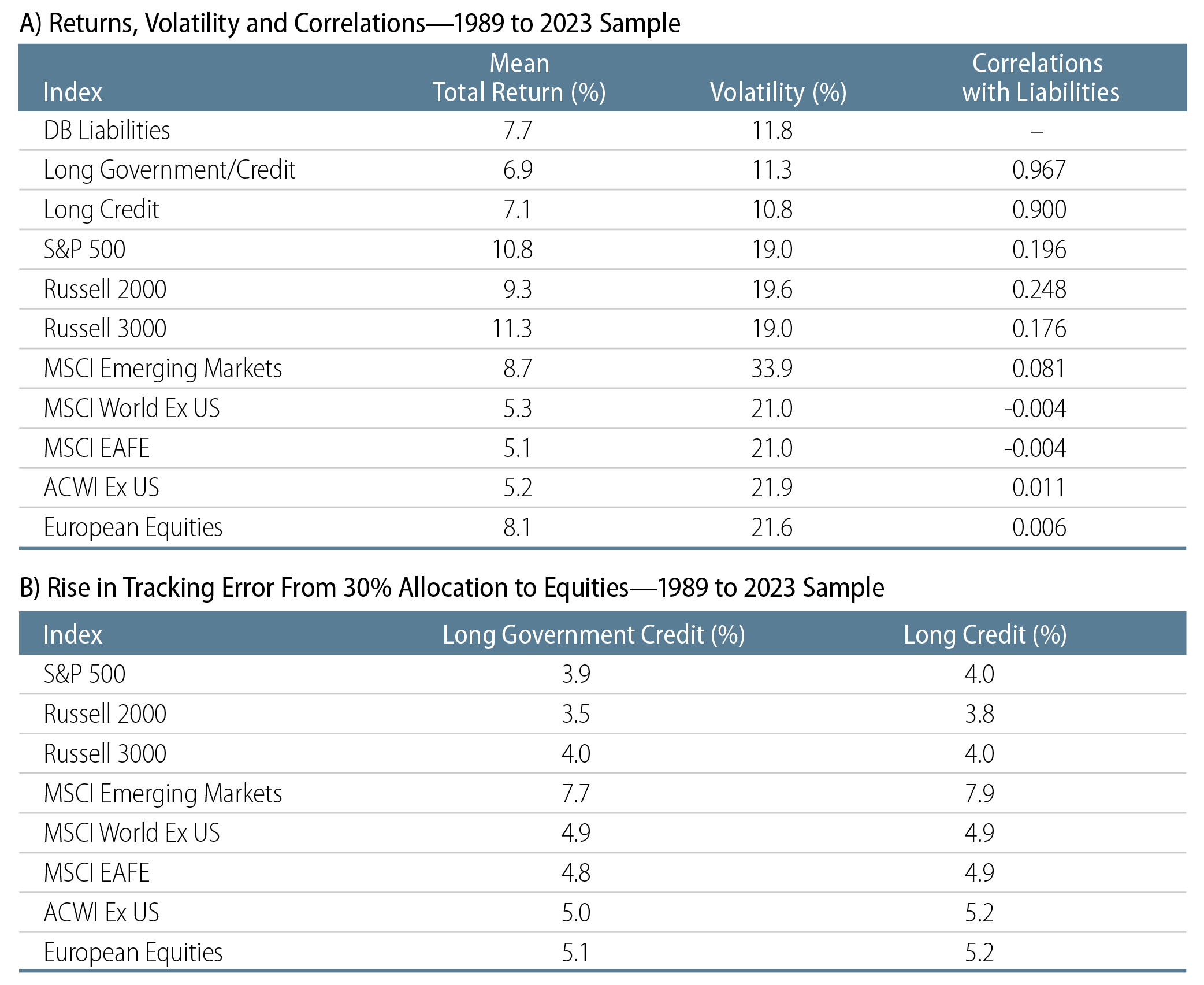

Our research has historically found negative correlations between US DB liabilities and all non-US equity indices, and that is reflected in the 1989-2020 sample results shown in Exhibits 1 and 2. When we reran the numbers to include recent results, we found that things had changed. With inflation and monetary tightening coordinated across DM countries since the pandemic, financial markets have become more concurrent or positively correlated.

(It is also the case that the tracking errors associated with 100% fixed-income have declined very slightly, to 3.3% per year for long G/C and 5.6% for long credit.)

As you can see in Exhibit 2A, a few non-US equity indices now show very slightly positive correlations with US DB liabilities over the 1989-2023 sample period. However, this doesn’t change the validity of our results. Remember, the formula shown in ② in the Just a Little Math section says that the closer to +1 the correlation between liabilities and assets, the lower the tracking error will tend to be.

And while the correlation coefficients between DB liabilities and offshore equities increase when the last three years are added to the sample, the correlation coefficients for US equities also rise, and they rise by as much or more than those for non-US equities. So, over the 1989-2023 sample period as well, investing in non-US equities would have increased tracking error relative to investments in US equities.

As you can see in Exhibit 2B, the incremental risk to a DB plan associated with investing in equities does not change significantly when the last three years of results are added to the sample. The post-pandemic world has seen lower average returns and more volatility than were experienced prior to the pandemic, but US and non-US markets (as well as bond and equity markets) have now shown more common variation.

Tracking error for all the various portfolio constructs is lower with the last three years of experience folded in, but the incremental riskiness of investing in US equities or in non-US equities remains about the same as was seen over the pre-pandemic experience. Under these results, it still is the case that investing in non-US equities primarily as a diversification tactic is misguided.

Conclusion

Virtually any investment mantra has its limitations and applies in some situations, but perhaps not in others. Diversification across assets is a great way to reduce the volatility of asset returns, but for a DB pension plan, return volatility is not the relevant risk metric. Rather, the tracking error against liability returns is the relevant measure of risk. To reduce its riskiness, a DB plan should look for assets that are positively correlated with its liabilities. In most cases, this will increase return volatility even as it reduces risk.

We have explored this point verbally, analytically, and empirically, reaching the same conclusions in each venue. Investing in assets not correlated to long bonds or DB liabilities might make sense on a return-seeking basis. It should not be done by a DB plan solely as a matter of portfolio diversification.