KEY TAKEAWAYS

- COP28 set ambitious goals for emissions reductions and renewable energy growth, but implementing the policies and transition presents challenges.

- The summit successfully secured pledges totaling $83 billion in climate financing, but significantly more investment is needed to reach net zero.

- Approximately 50 major oil and gas companies signed a charter to accelerate emissions reductions, but details are still needed on how they will meet their commitments.

- The renewable energy transition risks job losses, especially for fossil fuel workers, underscoring the importance of a ''just transition.''

- Understanding the climate policy landscape is one of the important factors for investment managers in assessing risks and opportunities and constructing portfolios.

COP28 has set ambitious climate goals and financial commitments. However, challenges remain in implementing these policies, financing the transition and managing the social implications of job displacement. As investment managers, it is important for us to understand the implications of these goals and the potential impacts on investee companies when constructing portfolios. The seminal statement from the 28th meeting of the Conference of Parties (COP28) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change focuses on a ''transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems''.1 COP28 also included the first global stocktake on progress made and concluded with an acknowledgment that human activities have resulted in global warming of 1.1 °C. The Global Stocktake will be a biennial process and focus on four key areas around climate change risks: mitigation, adaptation, implementation through finance, and technology and cooperation. The final report also called for reductions in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035, versus 2019 levels, reaching net zero emissions by 2050.2 The report also discusses a tripling of renewable capacity addressing methane flaring and the phasing down of ''unabated'' coal power, namely thermal coal power plants whose emissions are not captured using carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies. However, a failure to agree on standards around an emissions trading mechanism overseen by the United Nations, calls into question the ability to implement such policies.

Opponents have heaped scepticism upon the choice of transitioning away from rather than doing away with fossil fuels. However, given the magnitude of the climate crisis, proponents have praised the COP28 statement for its recognition at the COP28 meeting that while the evolution of the global economy from fossil fuels to renewables needs to happen, it will take time to achieve. COP28 was also important in noting that the transition needs to happen in a ''just, orderly and equitable manner''.3 The statement acknowledges the need to consider the social aspects around job dislocations arising from the energy transition and the variation in responsibilities that nations face based on their different circumstances.

Show Me the Money

COP 28 led to pledges of $83 billion across various projects. Some of the key financing initiatives stemming from COP 28 include the following:4

b. $792 million in a Loss and Damage Fund administered by World Bank for the first four years.

c. $187.74 million in a climate Adaptation Fund

d. $179.06 million to a Least Developed Countries Fund and the Special Climate Change Fund

e. $30 billion in commitments by the UAE to launch a catalytic climate vehicle, ALTERRA, to finance a fairer climate system, with goals to mobilise $250 billion globally by 2030.5

Additionally, the summit also welcomed efforts by developed countries to jointly mobilise $100 billion annually, as part of the ''new collective quantified goal on climate finance''.6 Notwithstanding the sums committed and the general concerns around inflationary pressures at the start of the summit, it is important to note that estimates by the International Energy Agency (IEA) project annual investment in clean energy power generation will need to increase from $1.8 trillion in 2023 to $4.5 trillion annually, to reach net zero goals.7 Additionally, when comparing the financing committed at COP28, it is useful to note that the climate change component of the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) itself amounts to $369 billion, three-quarters of it arising from tax incentives.8 The key to translate both the aspirational and functional aspects of financing will require private and public participation.

Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter (OGDC) and Methane Flaring

Around 50 oil and gas companies signed a voluntary global industry charter to accelerate climate action with a focus on reaching net zero by or before 2050, zero-out methane emissions, and eliminating routine methane flaring by 2030,9 which scientists estimate that methane has contributed between 20%-30% of global warming.10 The list includes major national oil companies (NOC)11 such as Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi National Oil Corporation (ADNOC), Norway’s Equinor, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation of India (ONGC), Indonesia’s state owned Pertamina, Petrobras from Brazil and China’s state-owned ZhenHua Oil, to mention a few. International oil companies (IOCs) include the likes of British Petroleum (BP), Eni, EQT Corp, Exxon Mobil, Occidental Petroleum, Repsol, Shell, Total Energies and Woodside Energy Group. Given voluntary pronouncements made by the oil and gas companies, further details are needed to understand how these firms expect to meet their goals.

As part of the need to decarbonise, discussions were also held around the need to reduce energy poverty and provide secure and affordable energy. Given the economic role played by the NOCs, the implications of a rapid decarbonisation to the national GDP and job losses, along with potential retraining and redeployment needs, would also need to be understood in order to achieve a just transition.

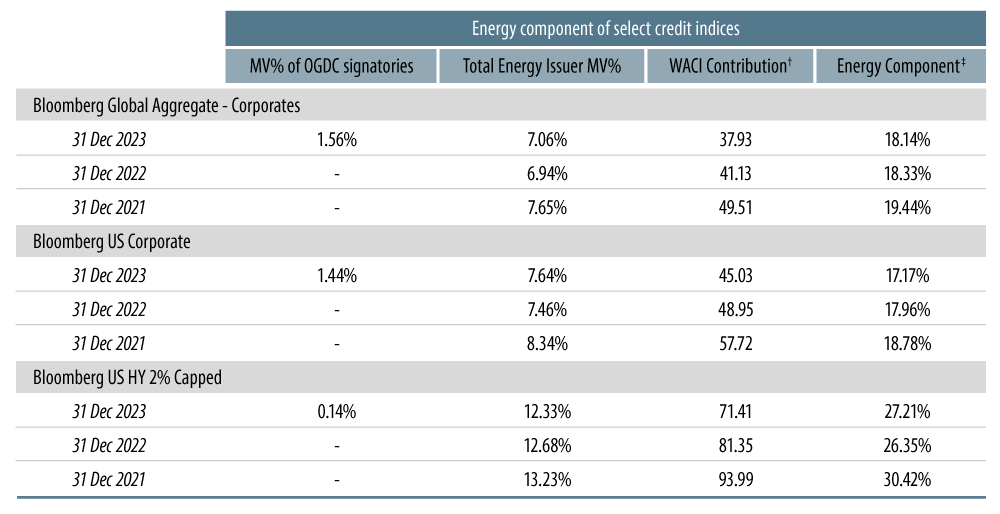

From a decarbonisation perspective, it is noticeable that the absolute Weighted Average Carbon Intensity (WACI) of the energy sector based on Scopes 1 and 2 emissions within select credit indices has fallen over the past three years, with varying degrees across three credit indices as shown in Exhibit 1. While some oil and gas majors have done better than their peers, clearly more reductions are needed to reach net zero commitments of emissions reductions as postulated by the UN. It is important to note that despite the commitments, the investment universe of energy issuers with such commitments within the various corporate bond benchmarks is small, which can create challenges when managing diversified portfolios, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.

Addressing the ''Social'' in the ''Environmental'': Challenges of Renewable Energy Jobs

The energy sector is one of the largest employers globally and is a key component of the economies of both developed markets (DM) and emerging markets (EM). COP28’s focus on a fair transition that takes workers’ unique needs into account is an acknowledgment that the social risks of the energy transition cannot be ignored. The IEA suggests that of the 65 million workers employed in the energy sector, nearly 35 million were employed within the clean energy sector, more than those employed in traditional fossil fuel jobs.12 The clean energy sector has also seen greater growth post pandemic compared to traditional fossil fuels.

However, it is also important to recognise that the energy transition is likely to involve the retraining of workers to move from fossil fuel sectors to those within the clean energy ambit. The IEA estimates that nearly half of workers facing redundancy in the fossil fuel sector have opportunities in the clean energy sector, with many being able to switch roles with just four weeks’ training. However, closer scrutiny would reveal that these statistic conceal the unequal consequences of job losses faced by different workers. For instance, workers who are unable to relocate to areas that offer renewable energy jobs are most at risk of job losses. While the IEA analysis suggests over 180,000 jobs being redeployed in mining critical minerals over the past three years13, this conceals the impact to those countries with a lack of access to rare earth minerals, thus precluding the ability for workers to be redeployed. For example, coal miners are at greater risk of job losses. There are profound implications for workers in countries such as China, India, Indonesia, the US and Australia, all of which are signatories to the Net Zero Paris aligned treaty and the five largest producers of unabated thermal coal. China alone accounts for nearly 50% of the total global thermal coal consumption. While expectations of absorption of job losses in core oil and gas sectors by growth in sectors such as hydrogen, carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS), electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries abound, it is imperative for countries and multilateral organisations to understand the social implications of job losses arising from the energy transition and the potential consequence on economic growth globally. Additionally, no country or company currently has access to a full suite of renewables and the ability for workers to seamlessly relocate or be redeployed to clean-energy alternatives in the absence of incentives, which may themselves have further financial implications.

Clean Technology: Understanding Headwinds

COP28 acknowledges that technology transfer, sharing and capacity building will be fundamental to the transition process. As part of this process, the UN Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN) is expected to play a key role in both mitigation and adaptation strategies. Current projects funded include a wide array spanning agriculture, circular economy, irrigation, renewable energy, water and waste management. However, the rate of adaptation from prototype to full adoption can take time and varies depending on supply-chain constraints, corporate R&D budgets, geopolitics and government policies and incentives. For instance, research conducted by the IEA suggests that even a 1% rate of adoption by corporates can take time from conception of the technology. While CCUS and hydrogen-related renewables are often touted as useful substitutes, Exhibit 2 suggests that adoption will be extremely low across this whole decade.

A study by Bloomberg NEF

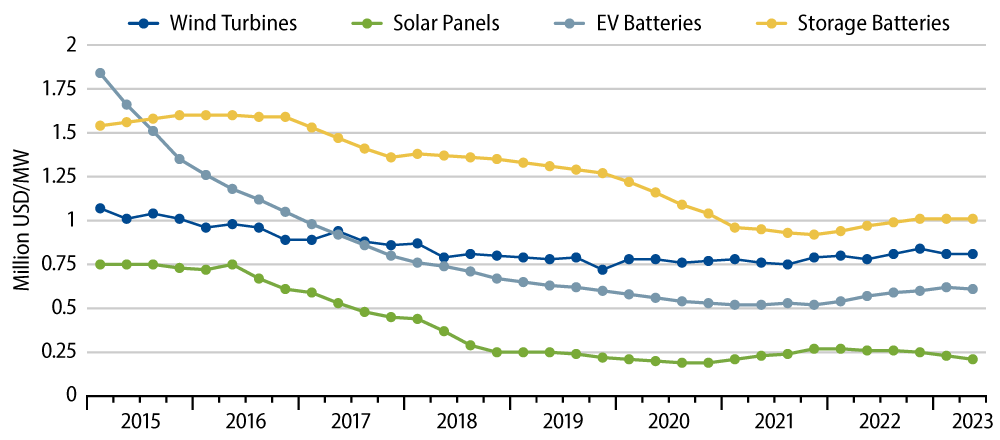

A further headwind facing greater adoption of renewables was seen in the form of high interest rates over 2023. While there has been a steady decline in the levellised cost of energy (LCOE) over the past few years, there are regional variations, which were compounded by higher inflation, resulting in an increase in the cost of manufacture of green technology). As illustrated in Exhibit 3, storage batteries and electric vehicles have seen greater increases, compared to solar panels and wind turbines. Many utilities globally have typically negotiated a fixed fee and then borrowed to finance the build out of infrastructure to provide clean energy. With rising rates and a diminishing of the ''greenium''19, it has become harder for these issuers to borrow at attractive rates. This has therefore led a decline in profitability with many utilities providers pulling out of financing renewables projects. Offshore wind has faced steep challenges over the course of the past two years. Some prominent recent casual- ties include, Orsted’s write-off of $4 billion in US offshore wind projects, BP & Equinor recording impairments of $540 million and $300 million, respectively, on projects to sell offshore wind power to New York, Iberdrola’s US subsidiary Avangrid cancelling their 804 MW Park City Project with Connecticut.

Better contracts, attractive market pricing and government policies may accelerate more investment in renewables. Successful projects include the UK government’s securement of 95 new projects in 2023, which includes schemes such as the Floating Offshore Wind Manufacturing Investment Scheme.20 Similarly, Australia’s Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) have made significant investments including $2 billion being earmarked for a Hydrogen Headstart program in December 2023.21 Also, Lafarge Canada has looked to tap into Canada’s investment tax credits (ITC), as part of its CCUS strategy. The ITCs were initiated in 2023 and are refundable tax credits to the tune if 30% of the capital cost of clean tech such as solar PV, battery storage, hydrogen and CCUS.

COP28's goals and commitments are a step forward in addressing climate change, but significant challenges in policy implementation, financing and social implications from job displacement remain. Technology adoption and innovation are critical, with government support playing a pivotal role in accelerating the shift to renewable energy. As investment managers, it is important to understand the opportunities and challenges stemming from policy pronouncements. Understanding the costs and timescales across which these play out and their impact on individual sectors and companies is important when constructing portfolios. It is important to monitor and engage with corporates that have made commitments to align with net zero goals. Understanding capex allocation and the implications of wider macroeconomic and geopolitical considerations on businesses’ decarbonisation strategies will be key to identify issuers that are best placed to transition using cost effective measures. While regulations and policies have provided a fillip to certain sectors globally, a continuity in incentives will be needed to meet decarbonisation goals. The impact of increasing inflationary pressures arising from such incentives would also be needed to be taken into account. And while the longer-term trend suggests that decarbonisation will continue, the rate at which companies reduce their emissions may vary. This creates an opportunity for managers to identify decarbonisation leaders and laggards, and to construct portfolios in keeping with clients’ decarbonisation guidelines.

- https://unfccc.int/news/cop28-agreement-signals-beginning-of-the-end-of-the-fossil-fuel-era

- https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma5_auv_4_gst.pdf

- https://unfccc.int/news/cop28-agreement-signals-beginning-of-the-end-of-the-fossil-fuel-era

- https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma5_auv_4_gst.pdf

- https://www.cop28.com/en/news/2023/12/commits-US$30-billion-in-catalytic--capital-to-launch-landmark

- https://unfccc.int/news/cop28-agreement-signals-beginning-of-the-end-of-the-fossil-fuel-era

- https://www.iea.org/news/the-path-to-limiting-global-warming-to-1-5-c-has-narrowed-but-clean-energy-growth-is-keeping-it-open

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1128#:~:text=The%20Inflation%20Reduction%20Act%20is,build%20a%20clean%20 energy%20economy

- https://www.cop28.com/en/news/2023/12/Oil-Gas-Decarbonization-Charter-launched-to--accelerate-climate-action

- https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/methane/#:~:text=The%20concentration%20of%20methane%20in,(which%20began%20in%20 1750)

- https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/energy-transition/120223-cop28-fifty-oil-and-gas- companies-sign-net-zero-methane-pledges

- https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-employment-2023/executive-summary

- https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-employment-2023/executive-summary

- https://about.bnef.com/blog/ccus-market-outlook-2023-announced-capacity-soars-by-50/

- https://www.iea.org/commentaries/how-new-business-models-are-boosting-momentum-on-ccus

- https://www.iea.org/energy-system/low-emission-fuels/hydrogen

- https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Hydrogen-Insights-2023.pdf

- https://www.energy.gov/articles/biden-harris-administration-announces-7-billion-americas-first-clean-hydrogen-hubs-driving

- Greenium refers to the premium paid for purchase of a labelled (green, social, sustainable or sustainability-linked) bond over its non-la- belled or traditional counterpart.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/news/record-number-of-renewables-projects-awarded-government-funding

- https://www.cefc.com.au/media/media-release/arena-announces-six-shortlisted-for-2-billion-hydrogen-headstart-funding/