Asia Pacific Regional Update: Warnings and Opportunities

As exemplified by the Chinese characters “危机”, danger is simultaneously a warning and an opportunity for investors who have the experience, resources and courage to exploit them.

Western Asset has investment professionals from three countries serving global investors in the Asia Pacific region. In this Q&A, three of our foremost regional investors, the Investment Heads of Western Asset’s Tokyo, Singapore and Melbourne offices—Kazuto Doi, Desmond Soon and Anthony Kirkham—share their investment insights from around the region.

DS: When I wrote China: What to Expect in the Next Six Months in August 2017, the usual concerns of high financial leverage, Chinese yuan depreciation and capital outflows were foremost in the minds of investors. My message then was that Chinese authorities would use time and resources in exchange for economic and FX stability. Fast forward to today and the Chinese yuan has been one of the strongest Asian foreign currencies.

President Xi Jinping has a new economic team, led by Vice Premier Liu He, which demonstrated their serious intent to reign in leverage as recent data show that leverage growth has flat-lined. Today, trade tensions with the US are an additional challenge for Chinese policymakers, but we are of the opinion that authorities have the know-how, resources and long-term focus to steer the economy towards consumption, high-technology and less reliance on leveraged investments.

KD: In the most recent quarterly report published on April 27, 2018 by the Bank of Japan (BoJ), “Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices,” the BoJ upgraded its growth forecasts for 2018 and 2019 from +1.4% and +0.7% to +1.6% and +0.8%, respectively, and revised down the inflation forecast for 2018 from +1.4% to +1.3%. A combination of steady moderate growth and persistent weak inflation characterizes the Japanese economy well. As you correctly point out, inflation has turned out to be much slower than BoJ expectations mainly because of conservative price setting across economic sectors due to the lagging effect of decades of deflation despite solid growth.

We expect that the BoJ will maintain the current monetary policy, or YCC (yield curve control), until actual inflation data reach the target level (2%) and stabilizes, given its overshooting commitment, because of the slower-than-expected developments of inflation. Other central banks in developed markets have started the policy of interest-rate normalization, while in sharp contrast, the BoJ continues to stick to the current policy.

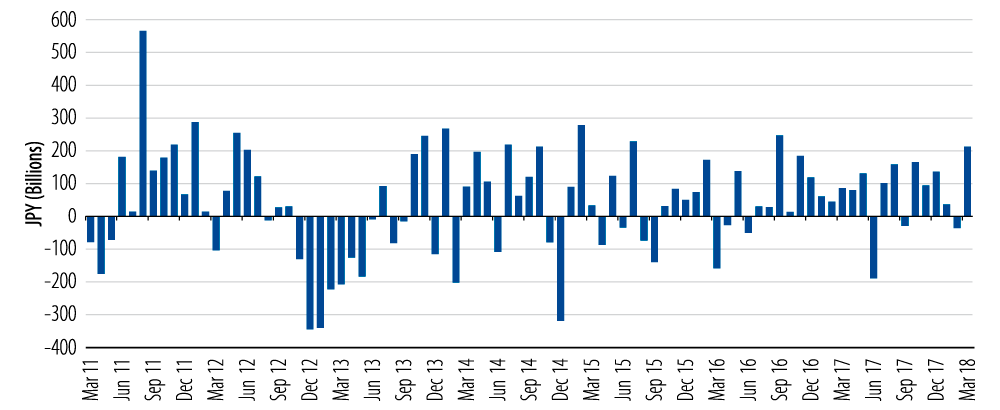

In our opinion, the BoJ has already started a kind of policy normalization when it pivoted to YCC from Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) in September 2016. The shift intended to make the extraordinarily easy monetary conditions as sustainable as possible for as long as necessary, by allowing the bank to reduce the amount of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) to purchase. As a result, the average annual increase of the BoJ’s balance sheet has actually fallen to ¥44 trillion from ¥80 trillion previously. Looking forward, the size of the BoJ’s balance sheet continues to expand at a much slower pace than before YCC. In adopting the YCC policy, the BoJ moved its policy target away from a quantity-based measure (amount of JGBs purchased) to a level of 10-year JGB yields and the overnight policy rate. Under YCC, we expect that a scenario of higher inflation expectations will drive real interest rates lower. In turn, lower real interest rates should boost growth and inflation over time.

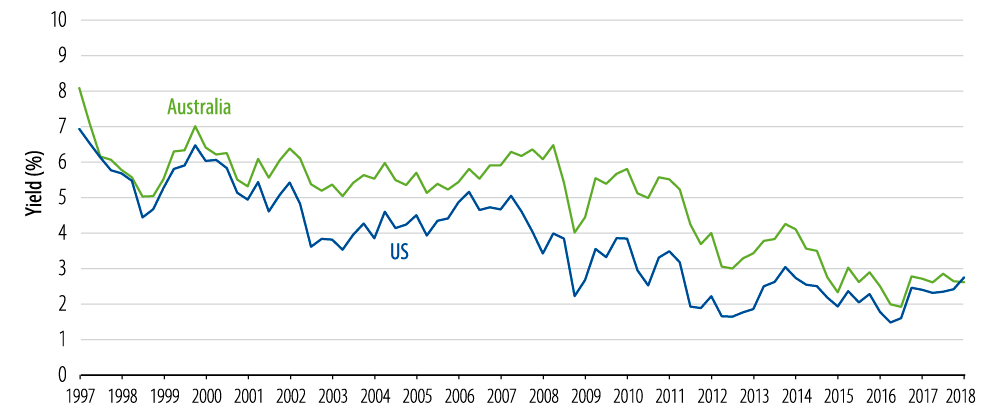

AK: The inversion between the US and Australian 10-year bond markets has been threatening for some time now and it finally breached in late February, which was the first time in 18 years. It is a far cry from the 2%+ gap just a few years ago that had yield-hungry investors plowing capital into Australian bonds. Interestingly, despite the hype in many circles, the move didn’t cause too many ripples and, in fact, the negative spread quickly moved to -10 basis points (bps) with little fanfare.

10-Year Government Bond Yields

Fiscal stimulus and tax reform in the US—introduced to an economy that is pushing the boundaries of full employment—have investors concerned about bond supply, inflation and the need for further Federal Reserve (Fed) action over the next two years, with the result being higher yields. In contrast, in Australia, we have markets pricing the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) as on hold until early 2019, an improving Terms of Trade that is driving a reduction in the government deficit and with constrained wage growth providing little pressure on inflation, Australian bonds appear relatively fair value.

Interestingly, global investors who used to chase Australian bonds for their yield advantage, in particular Japanese investors, are now more comfortable holding Australian bonds for capital preservation purposes. The underlying conditions and lower volatility that the Australian bond market offers versus the risks now inherent with the US in a “Trumped-up” world and the threat of quantitative tightening in Europe—these are all at play driving the current yield differential.

With regard to inflation, we expect Australia to be a member of the “low-wage party” for a little longer than most. Having been the standout for wage growth until 2015, thanks in large part to the greatest mining CAPEX boom in our history and the shortage of skilled labour that this generated, we are now looking like we could be one of the last to leave the party. This wage adjustment in Australia was required to build competitiveness again, but what is most surprising is that despite generating a record employment growth of more than 400,000 jobs in 2017 or 3.3%, the unemployment rate didn’t move downward. Offsetting this growth was the equally large annual increase in the employment participation rate of 0.9%, which left unemployment at 5.5% and, as a result, labour slack remains. This pushes out the likelihood of broader wage pressures until 2019 and with price competitiveness pressures across many retail sectors, inflation will stay gradual and the RBA will remain on the sidelines.

Japanese Investment in Australian Dollar Long-Term Debt

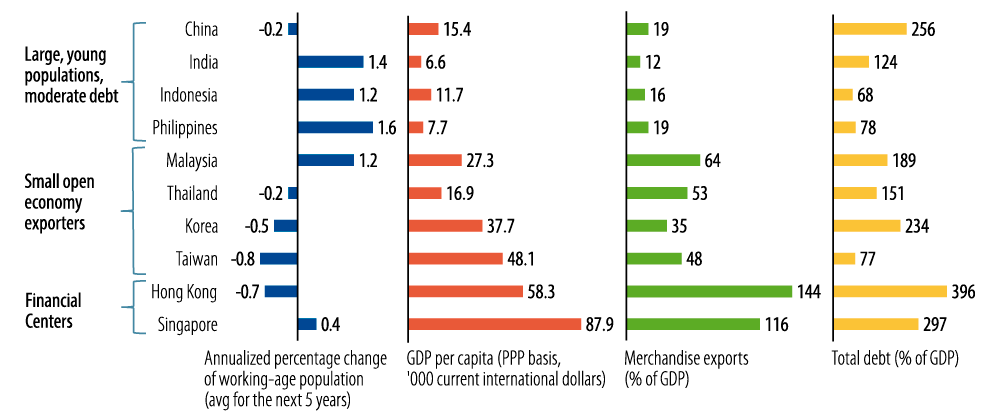

DS: As it has the world’s largest population, Asia is indeed growing economically and politically. Anchored by China, the region now accounts for 60% of global GDP growth. However, Asia’s geographical grouping masks important differences in individual country demographics, openness to trade, debt levels and potential growth rates as seen in Exhibit 3.

Asia Is a Heterogeneous Regional Grouping

Hence, fixed-income investors should not analyze Asia as a monolithic bloc but drill down on heterogeneous country fundamentals and idiosyncratic factors. For example, diversity is a source of strength, as there are countries in Asia that are “high-beta” to US interest rate trends while “low-beta” bond markets such as China and India are less open and, therefore, less subject to foreign capital flows.

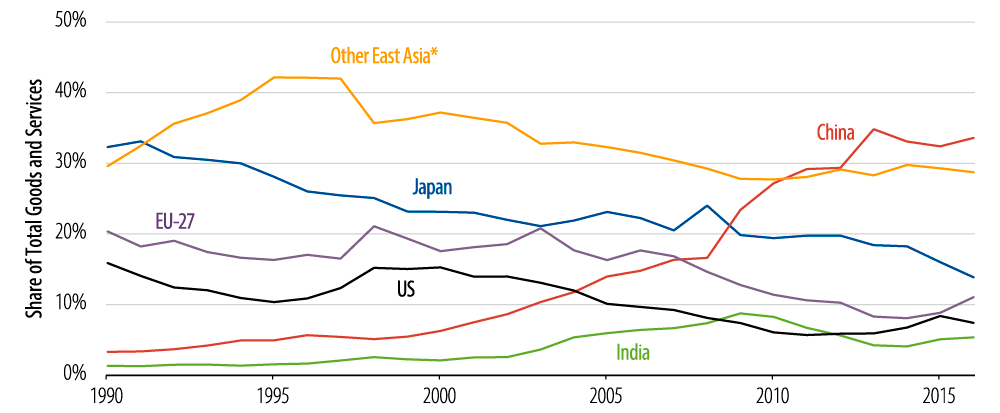

AK: The standout over this long period of outperformance, which includes a number of global shocks that could’ve easily tripped up Australia, including the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997/98, the tech bubble of 2000 and clearly the largest challenge, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008/09, was our ability to circumnavigate the latter. The major factor here was clearly our significant trade exposure to China where a massive fiscal stimulus focused on infrastructure, which had already supported the mining sector from 2005, was sent into overdrive. However, it would be simplifying the situation to only highlight our close ties to China as the sole reason. The RBA slashed the cash rate and its immediate impact on floating-rate loans at both a household and corporate level loosened financial conditions significantly while the huge fiscal spend and weak Australian dollar were also important for the competitiveness of both goods and services. Notwithstanding these and other drivers, it was the upswing in the global commodities cycle that followed between 2009 and 2012 that drove incomes in Australia and prevented a sharp rise in the unemployment rate and attendant social issues that have beset other economies.

Since the mining CAPEX boom ended in 2012, the Australian economy has transitioned from its reliance on commodities to a broader growth outcome. Asia has been a significant driver of this in sectors like tourism and education, thanks in a large part to the growing middle class in Asia and most particularly in China on the tourism front. The housing sector that was used to generate growth locally through easy monetary policy post the GFC has also been supported by capital inflows from Asia. As the demand for iron ore will wax and wane with infrastructure expenditure, Australia’s more consistent champion will come through energy. Coal has been a mainstay for a while but as countries including China lean more towards cleaner energy, gas exports will grow further and this will provide consistent economic support for Australia as a necessity for life throughout Asia.

Australian Exports by Destination

*Includes: Brunei, Cambodia, Hong Kong (SAR of China), Indonesia, Laos, Macau (SAR of China), Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Philippines, Singapore, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam

While China and Southeast Asia continue to grow at multiples higher than other advanced economies and as the region already represents more than 50% of our exports, it will remain a major driver for Australia over the medium term. Critically, however, with the linkages now so strong, one has to question our ability to continue this run of good luck, good management or both. With limited scope for monetary policy to assist as rates remain stuck at historically low levels—with our own fiscal headwinds due to a lack of taxation and expenditure reform—these ties to Asia have taken on a much greater level of importance. If they were to stumble, our record run would likely come to an abrupt end as our support levers would no longer have the power that they once had.

KD: Japan has been known for its ageing society, with low growth and deflation. Yes, that is still the case but the situation has changed rapidly over the past few years. More Japanese corporations operate in Asia to take advantages of the growing market and more Japanese banks have increased loans to businesses outside Japan. Overseas loans by Japan’s mega-banks currently account for more than 30% of their entire loan book.

The number of travelers to Japan increased significantly over the past few years. From eight million in 2012, to over 24 million in 2016. This increase has had a meaningful positive impact to the Japanese current account surplus.

A bit surprising to some, the number of immigrants was about 2.5 million in 2017, larger than the population of the city of Nagoya, the fourth largest in Japan. In fact, the number of immigrants to Japan is the fourth largest in the developed world, following the UK. Most immigration to Japan comes from other parts of Asia.

Increasingly, Japan and other Asian countries are more connected and interdependent both in terms of growth as well as demographics.

KD: I think I speak for all of us here when I say that globally, Western Asset believes that growth and inflation continue to improve, albeit from very subdued levels and central banks remain very cautious as they signal their path to normalization. We recognize the cyclically synchronized global growth but, at the same time, there remain global structural headwinds. We take cautiously optimistic approaches with an emphasis on investment diversification.

In terms of investment opportunities in Japan, we believe inflation-linked JGBs (JGBi) are compelling as inflation expectations are likely to rise under the YCC policy. We expect the JGB yield curve to likely steepen, especially with 10-year yields pinned under YCC as growth and inflation rises.

DS: The gradual opening of China’s large (US$10 trillion) onshore bond market, which will soon constitute 5.5% of the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, presents an immense opportunity for global fixed-income investors, including Western Asset.

Escalating trade tensions, higher US interest rates and oil prices represent dangers to Asian bond investors. On the other hand, given ageing demographics and sizeable current account surpluses in developed Asia, the region has the globe’s largest private and official savings. With a re-pricing of Asia government and corporate bond yields, judicious credit selection in a region whose local currencies are supported by sizeable current surpluses and non-profligate government finances offers diversification benefits as well as an opportunity for global bond investors.

Consequently, the ability to invest in an actively managed pan-Asian local currency portfolio is likely to deliver global investors both attractive yields (perhaps compared with home markets) and an Asian FX allocation.

AK: Western Asset expects Australian economic growth of 2.75% to 3.0% for the year, with the Australian dollar to come under increased pressure, finding support around the mid-US$0.70 range. Incorporating comments from above, we have retained our mild underweight duration and yield-curve-steepening positions in the 3- to 10-year tenors for our clients’ portfolios in the face of this outlook. We also continue to hold a flattening position in the 30- versus the 10-year tenor as a ballast to our overweight credit positions and because long-dated Australian bonds continue to stand out relative to other developed markets.

From a sector perspective, we maintain an overweight to corporate bonds with a concentration in large financials, property trusts and utilities, focused on shorter maturities to manage spread risk. We may seek to selectively add where market volatility has forced spreads wider than credit fundamentals would justify or as new opportunities present themselves.

Endnotes

- Morningstar Awards 2018©. Morningstar, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. Best Asia Bond Fund, Singapore 2018: Legg Mason Western Asset Asian Opps A USD Acc (ISIN:IE00B2Q1FD82) - Awarded to Legg Mason Western Asset for Morningstar Fund Manager of the Year, Fixed Interest Category, Australia.