Over the past few months the Federal Reserve (Fed) has meaningfully altered its assessment of appropriate policy for 2022. Based on Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s comments at today’s press conference, it appears the current plan is to raise rates starting in March, slow the reinvestment of maturing securities shortly thereafter, and stand ready to accelerate the hiking program should inflation stay persistently high. This plan would remove accommodation much sooner and quicker than it was removed during the previous cycle, and even much sooner and quicker than officials anticipated just a few months ago. Markets have repriced significantly to reflect this change in the Fed’s plan.

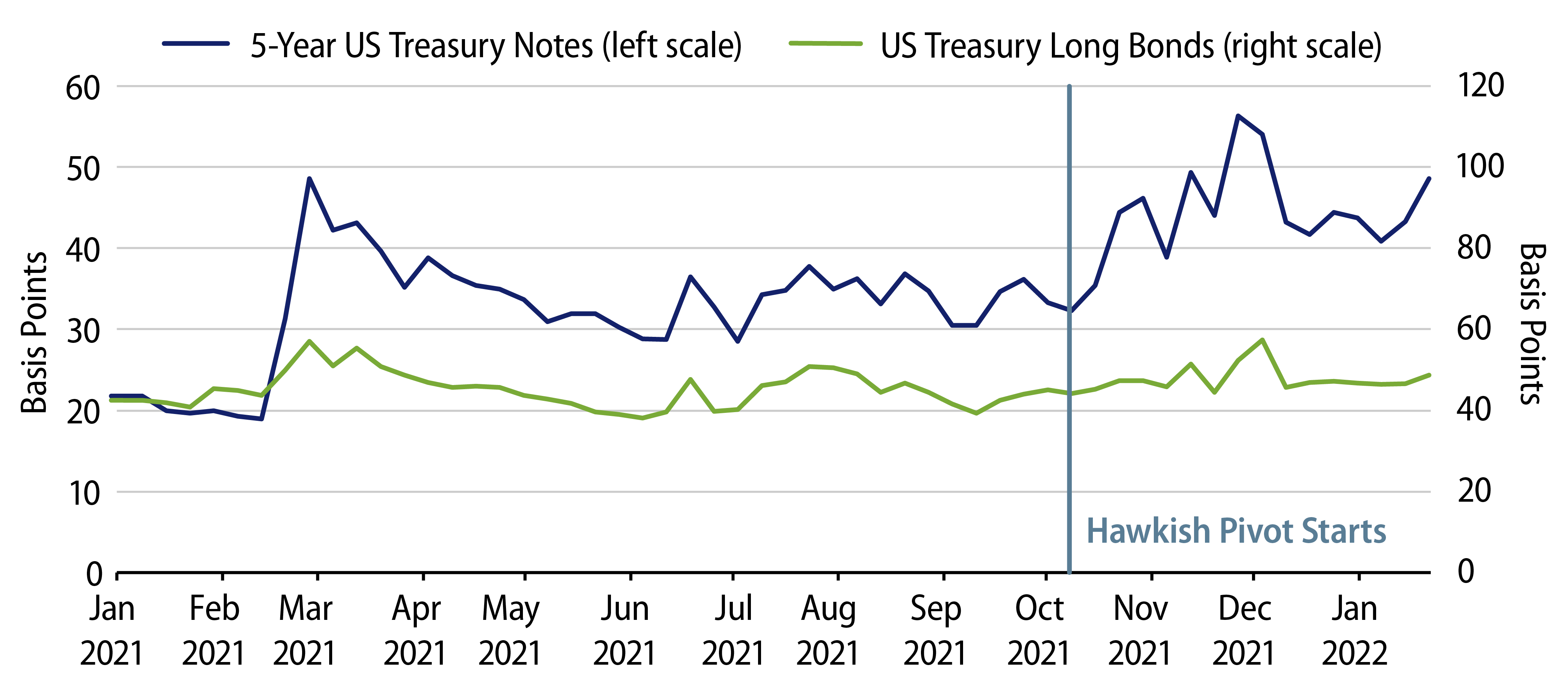

The abruptness of the change in the Fed’s assessment has also led to a considerable increase in the expected volatility of interest rates, and in particular, of interest rates on shorter-dated bonds (Exhibit 1). The implied volatility on 5-year US Treasury note futures rose in October when the Fed started to shift its rhetoric and has stayed elevated since. According to pricing in options markets, a one standard deviation range in yields on 5-year Treasury notes is approximately 50 bps over the next month alone. This is double what the options market had priced as a one standard deviation range in yields last summer. Significantly, implied volatility has stayed elevated even as yields have risen and are now pricing in a much quicker Fed cycle. The market is suggesting that even though a lot more is now priced for 2022, the risks are high that the Fed needs to continue to adjust from here. Also notable is that the implied volatility on longer-dated bonds has remained unchanged during this period, suggesting that the recent repricing in yields is much more about the path of the Fed than the underlying trend of economic growth or inflation.

It is not uncommon for a significant repricing to be accompanied by a large rise in expected volatility. Perhaps the current combination of higher-than-before yields and higher-than-before expected volatility is just the sign of another market in the process of adjusting. We suspect, however, that the elevated level of expected volatility says something slightly more nuanced about the Fed’s pivot. As everybody understands, the hawkish Fed pivot has led to a repricing of expectations for 2022. But what has complicated the matter is that during this reassessment, the Fed has also backed away from providing forward guidance. The specific words that the Fed has used to anchor expectations of policy rate changes in the past—“measured” from 2004 to 2006 and “gradual” from 2015 to 2018—have been absent from recent Fed communications. Indeed, today was no different, as the post-meeting statement didn’t make any attempt to shape expectations on the pace of hikes. Chair Powell similarly demurred from providing concrete guidance, responding to a number of questions about the pace of hikes by saying only that the Fed would “adapt as appropriate.”

What Else Could Anchor Yields?

The Fed’s plans, whether clearly laid out or not, are only one of many factors that influence yields and the expected volatility of yields. Ultimately the market will price not what the Fed plans to do, but instead what the market expects the Fed to do. This, therefore, requires the market not only to reflect the Fed’s plans but also to reflect an assessment of the outlook for the economy and for other financial markets. In the absence of an anchor from Fed guidance, these other factors are potential candidates to serve as anchors for yield levels and volatilities.

Growth data could become an anchor for yields in the near term. When the Fed started its hawkish pivot in November 2021, it was responding to the very strong October economic data, which had come in above expectations on all dimensions: growth, jobs and inflation. The data since have been much less straightforward, and there have been some concerning prints suggestive of a slowdown. On the one hand, the unemployment rate fell and inflation has stayed elevated. On the other hand, nominal retail sales have declined two months in a row and nonfarm payrolls have been materially below expectations. Omicron has likely distorted the December and January data. Covid-induced economic uncertainty is not new, however, and while it may distort the signal for a bit, it is unlikely to render the growth data completely irrelevant. The concerning data started before omicron arrived. If the slowdown persists or even broadens after omicron recedes, then markets would likely take notice.

Of course, the inflation outlook will play an outsized role in the levels and volatilities of yields for the remainder of the year. Over the next few months inflation is likely to remain elevated. But after that, Western Asset expects inflation to moderate, potentially by the middle of the year. Many have pointed out that certain aspects of measured inflation tend to lag, or at least that they tend to persist for a while after an initial step up. Housing is one prominent example. Many analysts expect measured inflation to be impacted by elevated contributions from housing costs throughout 2022, in large part because measured inflation has not fully reflected all of the increase in housing costs that occurred in 2021. Markets are not bound to the conventions of measured inflation, however, and it seems likely that investors will look through quirks such as these. If the higher frequency data on housing costs were to turn lower, markets would likely respond accordingly, regardless of whether measured inflation stayed elevated for a few months afterward.

The broader point is this. As the Fed has pulled back from providing an anchor through its guidance, markets will naturally look for other anchors to guide yields and volatilities. In particular, in the absence of an anchor from the Fed, the market is likely to rely on the economic outlook—and the corresponding data releases—disproportionately more in order to guide yields and volatilities. Either the growth data or the inflation could serve in this role, and on both accounts there is a possibility that the anchors emerge rather quickly.

An Eventual Return of the Fed Anchor?

Looking further ahead, it’s possible to foresee how the Fed anchor could eventually reemerge. Ironically, the foundations may have been laid already in the justification Chair Powell gave for the current hawkish pivot. In explaining the hawkish pivot, Powell has said that it is necessary to control inflation because high inflation, and the Fed policy that high inflation might eventually require, is “one of the two big threats to getting back to maximum employment.” He went on to say that “we need another long expansion … that’s what it would really take to get back to the kind of labor market we’d like to see.” Powell was acknowledging the concern that high inflation raises the risk that the Fed would be forced to respond sharply, which in turn could jeopardize the ongoing economic expansion.

Taken at face value, this may be a logically consistent reason to start removing policy accommodation. It is not, however, a reason why the Fed would, on its own, choose to escalate the removal of accommodation. To the contrary, if the Fed has pivoted now in order to avoid a sharp change in Fed policy in the future, then that suggests Powell and others would be very hesitant to precipitate that very risk by initiating a sharp change in policy on their own.

Another important aspect of Powell’s statement is its emphasis on the labor market. Indeed, for all of the talk about addressing inflation, the Fed remains focused on protecting and nurturing the labor market recovery. There is ample reason for the Fed to remain concerned about the state of the labor market. While some indicators suggest a healthy labor market, and perhaps even tight labor markets in some cases, the bigger picture is that today the US economy has far fewer jobs and far fewer workers than it did prior to the pandemic. Accordingly, any actions that prematurely end the expansion could have negative long-term implications for the labor market and the overall capacity of the US economy. The clear implication for monetary policy is that a steady and well-communicated path is preferable to one characterized by ongoing uncertainty.

Conclusion

Today the news is dominated by surprisingly high inflation and the hawkish Fed pivot that the high inflation has caused. Markets have responded by not only repricing the expectations for Fed policy this year, but also repricing the level of expected volatility in short-term interest rates. The lack of an anchor from the Fed has contributed to the repricing of volatility during this period. Looking ahead, there are a number of possible ways in which an anchor for yields could be reestablished. One possibility is the economic data may emerge as an anchor. Recent growth data has been mixed, with signs of a concerning slowdown in some sectors. The inflation data may also anchor yields, especially if it were to moderate considerably over 2022, as Western Asset expects it to. Finally, the Fed may itself reemerge as an anchor, given its focus on extending the labor market recovery and its stated objective of avoiding a sharp change in policy.