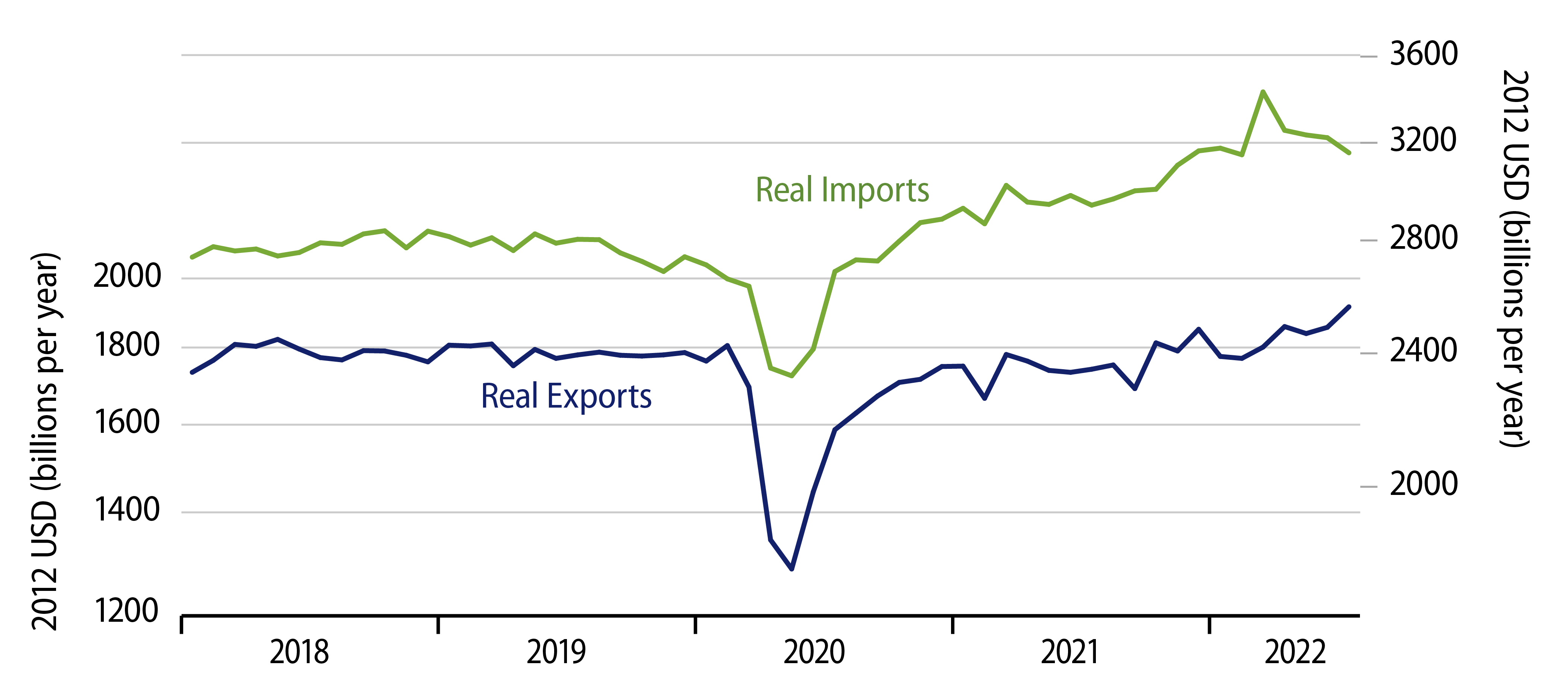

The real (inflation-adjusted) US merchandise trade deficit narrowed substantially in July, thanks to both rising exports and falling imports. Real exports rose 3.2%, thanks to a 5.3% rise in exports of industrial supplies (mostly oil) and a 3.9% rise in exports of capital equipment. Real imports declined by 2.1%, more than fully accounted for by a 9.7% plunge in imports of consumer goods.

Indeed, real imports of consumer goods have declined by a cumulative total of 17.4% (non-annualized) from their March high. That imports of consumer goods dropped so sharply indicates why this swing won’t provide any boost to 3Q GDP growth.

Yes, imports subtract from GDP in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) accounting, so by itself, a decline in imports provides a boost to GDP. However, swings in imports never occur by themselves. With less volume of consumer goods coming into the country, either consumer spending on goods will be less or else inventories of consumer goods will be depleted. In either case, those declines exactly offset the partial boost to GDP accounted for by lower imports.

On the other hand, the increase in exports is a clear and net boost to GDP growth, and it was nice to see capital goods exports rising so nicely. However, that July gain in capital goods exports merely offsets the declines in capital goods exports seen in May and June, leaving them unchanged on net since April. Similarly, oil exports have been gyrating around a flat trend, and July gains merely offset May declines.

In total, there was a net lift to total exports in July, but with developed market (DM) central banks tightening and Asian growth slowing, the odds of a sustained improvement in US exports are not high. As for imports, these have generally been declining for the last five months, paced by the aforementioned plunge in consumer goods imports. Again, this eases some of the pain from declining inventory investment but is not really a boost to growth per se (because domestic demand for goods is declining slowly but steadily).

One distinctly favorable turn in these data was that average prices declined in July for both exports and imports. Yes, falling oil prices accounted for some of this, but prices of non-petroleum traded products declined as well. The price deflator for all exports dropped 2.7% in July, while that for non-petroleum exports dropped by 1.0%. The price deflator for all imports dropped by 0.9%, while that for non-petroleum imports dropped by 0.4%. The latter also saw a 0.5% decline in June.

We take both the recent drop in import prices and the months-long decline in imports as indications that goods supply has caught up with goods demand—in the US at least—as the 2021 supply-chain disruptions and backlogs of unloaded container ships have eased markedly. This is an inflation story more than it is a growth story, and it augurs for continued moderation in goods prices—and thus for prices in general—in consumer price reports for months to come.