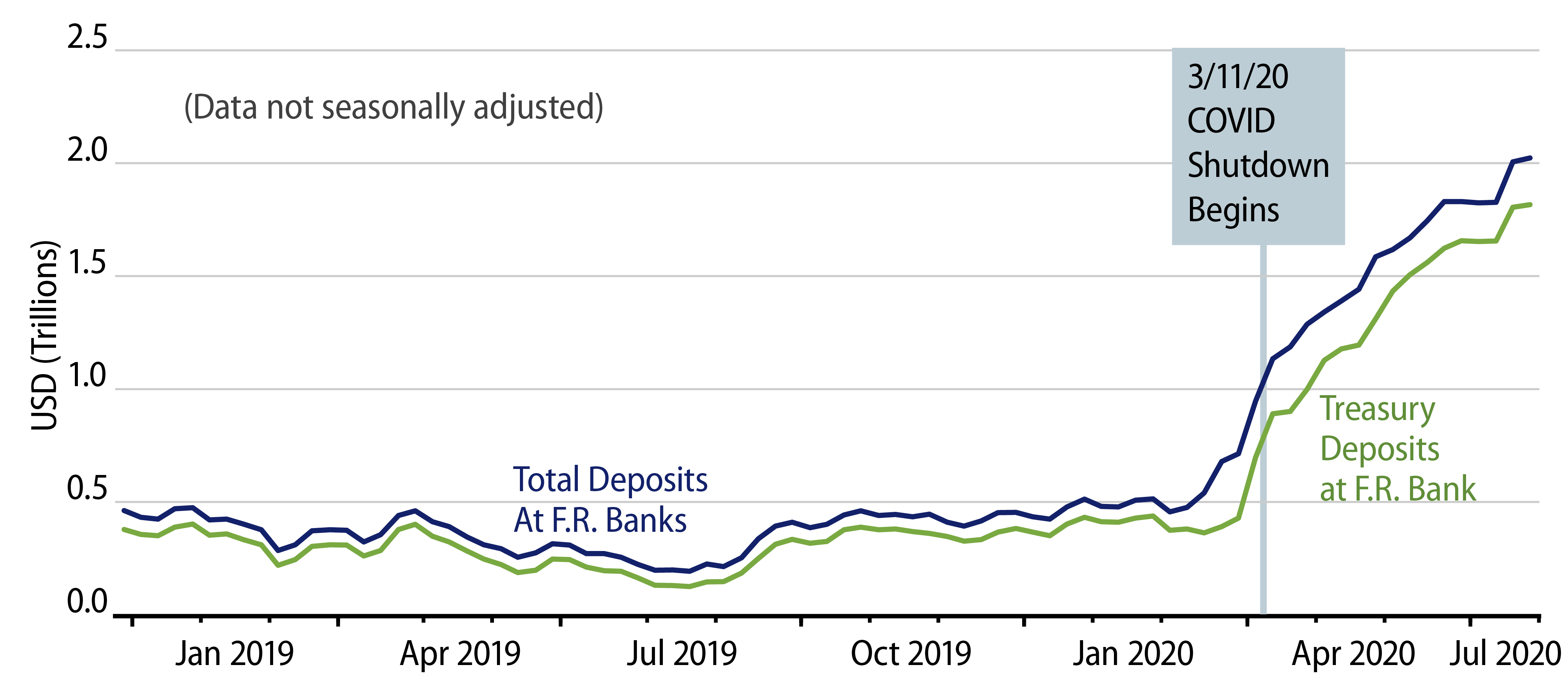

Just as businesses and consumers have moved to shore up cash holdings (liquidity) in the last few months, so too the Treasury has built up massive amounts of cash holdings—more than $1.5 trillion worth of accumulation. And while deposit build-ups by you or me are put into banks or mutual funds and are then potentially recycled into the economy, Treasury-accumulated hoards are deposited at the Fed and thus effectively drained from the financial system.

To put it more succinctly, if the Fed buys, say, $100 billion of T-bills from the Treasury, and the Treasury turns around and deposits the proceeds back at the Fed, the Fed’s balance sheet has expanded by $100 billion—Federal Reserve Credit is larger by $100 billion—but funds available to circulate in the economy have not changed at all. And the fact is that the Treasury’s build-up of “cash” since the onset of the COVID shutdown has soaked up more than half of the liquidity purported to be provided by the Fed over that period.

There’s nothing sinister about this process. I am not complaining about it nor lauding it. I am only pointing out that if you are worried about inflation prospects because of all the Fed activity, then the potential problem is less than half as large as you might think it is. By the same token, if you want to credit the Fed for its efforts to keep the system afloat, then its real accomplishments are less than half of what you might think they are. And if you are wondering why T-bill yields haven’t had any upward pressure even with all the government borrowing, this is part of the reason. In other words, the government’s borrowing was largely self-financed.

Again, most of what the Fed has done in the last five months was necessary just to offset the contractionary effects of the Treasury’s cash build-up.

Of course, the Treasury didn’t amass this hoard for the heck of it. It will likely work down its cash pile when and as the next stimulus round passes. Still, for now, more than half of the balance sheet expansion by the Fed since March has been offset by the Treasury’s cash build-up. When and as the Treasury starts to work this down, the Fed can offset those effects by shrinking its own balance sheet (without ill effect on the economy or bond yields, as the Fed would merely be absorbing funds injected into the system by the Treasury).

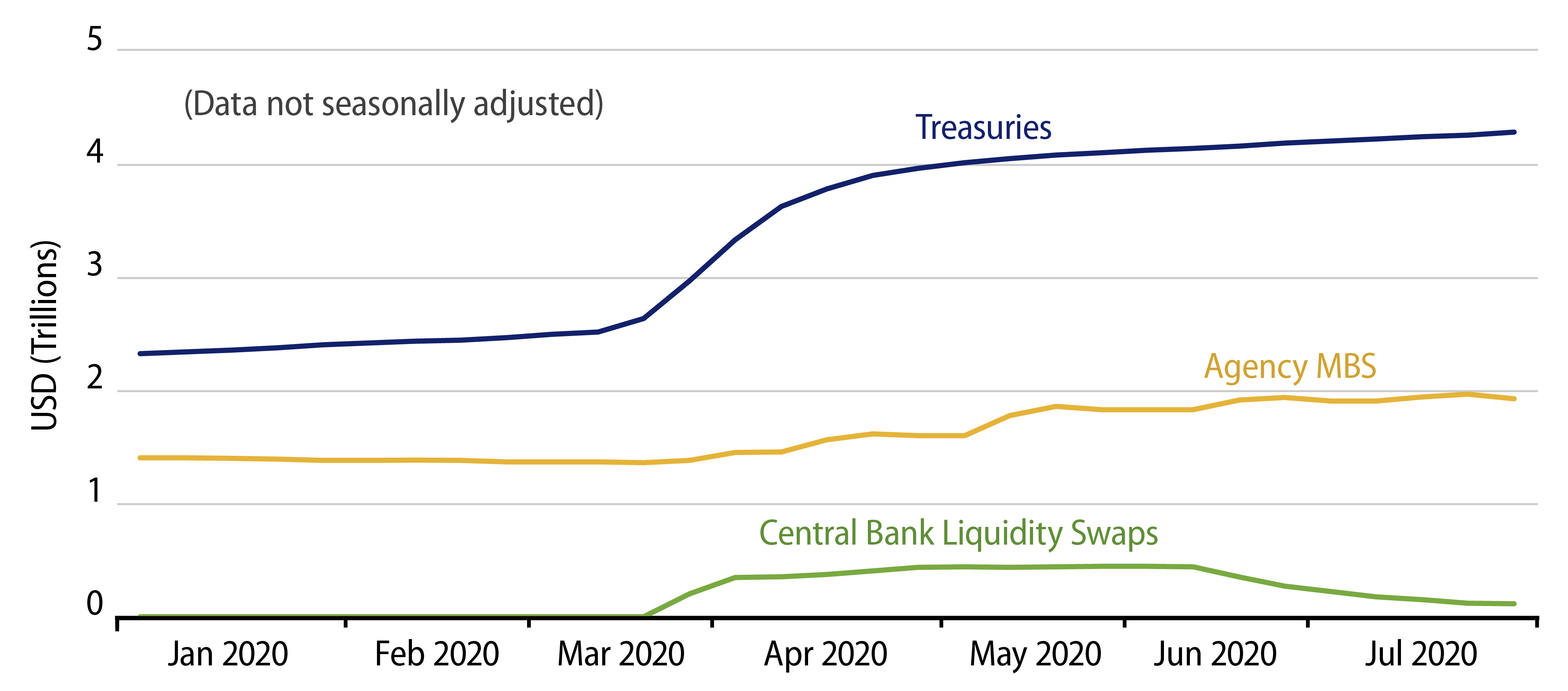

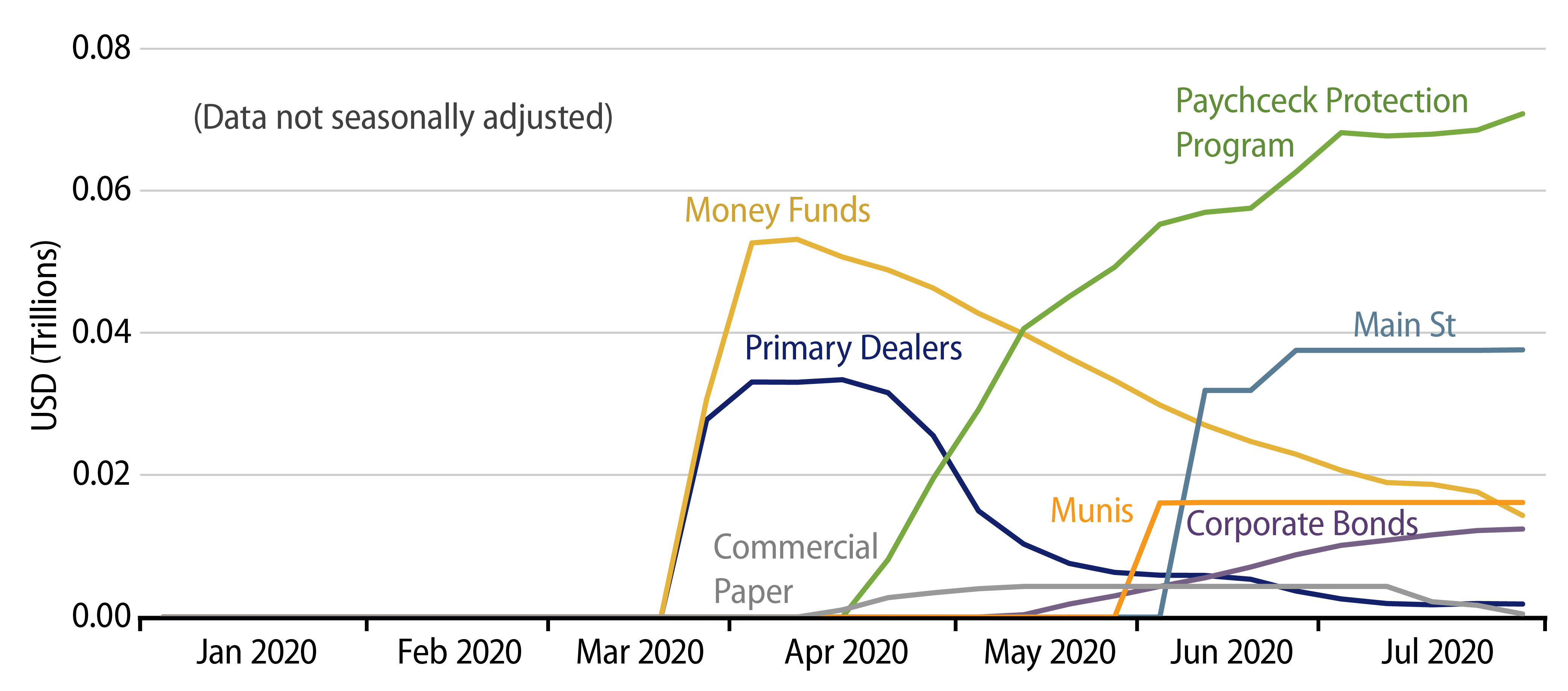

Exhibits 1 and 2 above make this point. In Exhibit 1 you can see that the total increase in Fed Credit (the Fed’s balance sheet) since March is much larger than the increase in the monetary base (Fed credit in private hands). In Exhibit 2, you can see the reason for the disparity: the sharp increase in deposits at the Fed, most of which are owned by the Treasury.

Meanwhile, Exhibits 3 and 4 below show the details of Fed activity. Outside of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and Main Street, the Fed’s “special facilities” continue to be worked down, so much so that Fed credit actually declined in the last few weeks, despite the Fed’s continued purchases of Treasuries. This is a bane to those thinking the Fed must do more, but hopefully a balm to those who believe the Fed has already done too much.