Here we explain the recent unprecedented turmoil seen in the UK gilt (government bond) market and the nearly constant stream of game-changing developments around UK fiscal policy and the Bank of England (BoE). With the gilt market currently in a period of relative calm this is an opportune time to review recent events, their impact on markets and to reassess our investment view.

A Review of Events

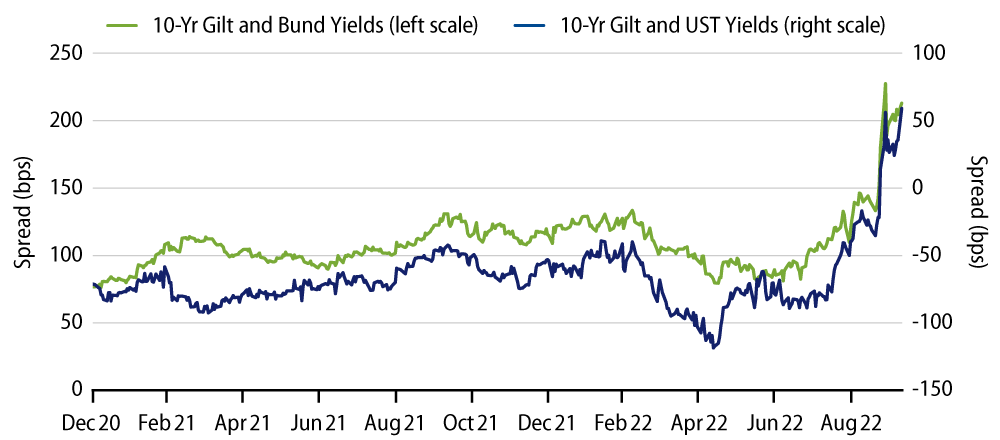

The most widely accepted catalyst for recent UK market turbulence was the UK government’s “mini-budget” on 23 September. The centrepiece was £45 billion of unfunded tax cuts without accompanying independent forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s fiscal watchdog, that would typically come along with such an announcement. The almost vertical rise seen in UK gilt yields relative to US Treasuries (USTs) and German bunds around the time of the announcement supports that (Exhibit 1).

However, Exhibit 1 also highlights that gilts had begun to gradually underperform prior to the mini-budget announcement, creating a very fragile environment in the lead up. Some reasons for this included:

- UK consumer price inflation surprised to the upside (10.1% in July).

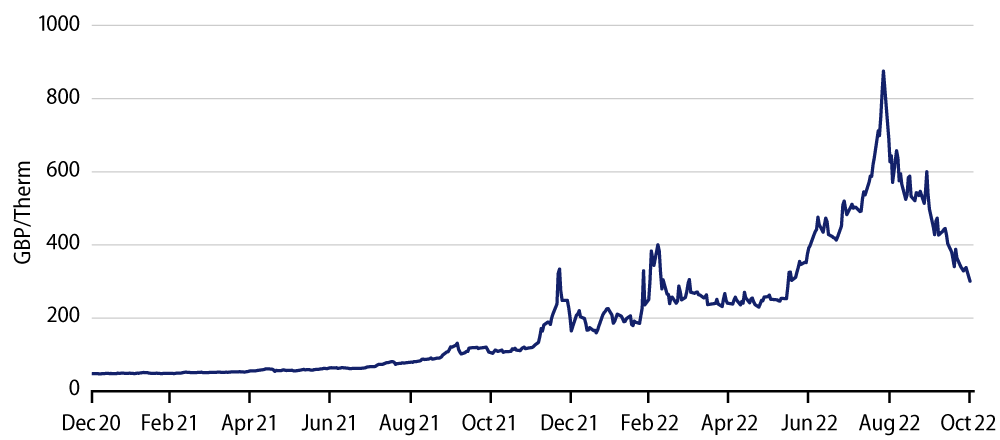

- Natural gas prices rose sharply (Exhibit 2) following Russia’s decision to stop flows to Germany through the Nord Stream pipeline.

- Together, this combination led some economists to forecast UK inflation rising above 20% next year as higher wholesale prices passed through to household energy bills.

- This led to an upward re-pricing of rate hike expectations from the BoE over the coming 12 months.

- All these events also took place during a period of political paralysis due to the resignation of Prime Minister Boris Johnson in July, with his successor, Liz Truss, only being confirmed early in September (although she was the front-runner and markets began to factor in a looser fiscal stance).

- In recent Monetary Policy Committee meetings, the BoE had reaffirmed its plan to begin active quantitative tightening (QT). This would mean selling some of the gilts that had been purchased previously during quantitative easing (QE).

- Market liquidity was thinner than usual during the summer period amid high uncertainty over further interest-rate increases globally.

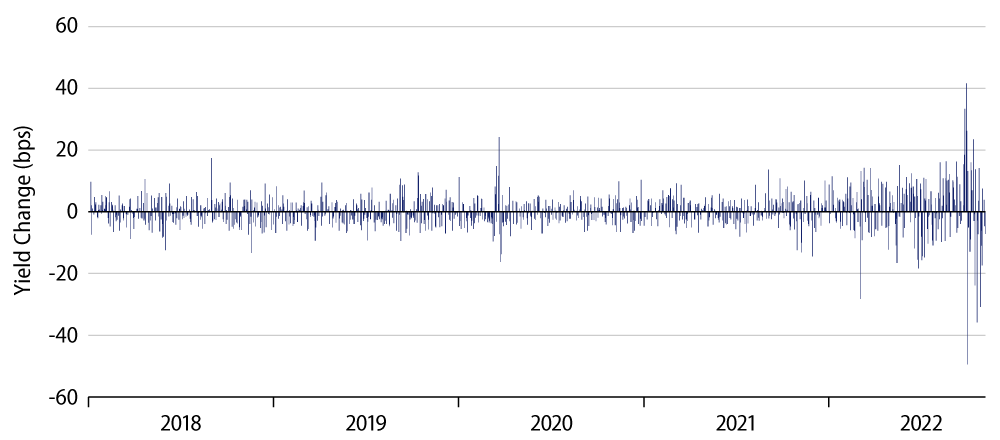

The outsized rise in gilt yields (Exhibit 3) in turn led to huge margin calls related to derivative exposures, particularly those of liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies commonly used by defined benefit pension schemes in the UK. This led to “fire sale” dynamics whereby some LDI strategies became forced sellers of UK gilts in order to raise necessary cash.

In response to this, on 28 September the BoE announced temporary emergency intervention to purchase up to £65 billion in long-dated gilts (the part of the curve that saw the bulk of the LDI-related selling). The BoE stressed that this intervention was needed for financial stability—acting as a buyer of last resort rather than aiming to drive yields lower as part of its monetary policy stance. The BoE also announced a delay to the start of its active QT programme that was due to commence on 3 October.

The gilt market took further reassurance from initial U-turns on some of the tax cuts, a promise for a detailed fiscal strategy (including spending cuts to ensure falling debt/GDP in the medium-term and alongside full OBR forecasts) and then subsequently from the resignations of both Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng and Prime Minister Liz Truss.

The new Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has since reversed most of the proposals from the mini budget and the new Prime Minister, ex-Chancellor Rishi Sunak, is seen as more orthodox in his economic approach. These new appointments served to restore confidence and stability as highlighted by the yield spread between gilts and USTs, which returned to August levels (Exhibit 4). A revised fiscal strategy will be presented on 17 November, alongside full OBR forecasts.

Another notable sign of the recovery in gilt market conditions is that the BoE was able, on 1 November, to begin its active QT programme. £750 million of bonds were sold without issue. This is historic as the BoE became the first major central bank to take such a step, but there is relief that the market could absorb the securities when this seemed unimaginable just one month earlier.

Our Investment View Revisited

Amid the mini budget upheaval markets priced more than 200 bps of cumulative rate hikes from the BoE by the November meeting, including an intra-meeting hike. The rationale behind this was that additional tightening would be required due to higher inflation expectations stemming from easier fiscal policy and a materially weaker currency (sterling fell at the same time that gilts were selling off). We viewed this market pricing as extreme. The subsequent developments were more consistent with a smaller amount of tightening and, in the run-up to the meeting, market expectations coalesced around a much smaller 75-bp increase, to 3.00%, which was subsequently delivered.

Currently, the market is pricing the Bank Rate to reach 4.75% next year (pricing was above 6.25% at one point), a level that we believe remains excessive given a very weak growth outlook and higher mortgage rates—especially given that households’ real disposable incomes are already under acute pressure due to higher food and energy prices. The BoE will also be relieved that sterling has reversed the weakness seen post the mini-budget and that natural gas and other commodity prices have continued to decline. If we are right in this view, gilts have further room to outperform, supporting our overweight stance.