The Commerce Department, specifically, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) within Commerce, today announced data for August on consumer spending, personal income, and PCE inflation. The releases also included benchmark revisions of these data back to 2019.

Total real consumer spending showed a 1.8% annualized rate of increase in August, with goods spending up at a 0.4% per year pace and services up at a 2.4% per year pace. Real personal income rose at a 1.4% annualized rate, while real disposable income and real wage income rose at 0.8% and 4.6% annualized rates, respectively. We show the annualized real rates here partly to make these numbers comparable to real GDP growth that has been in the 2% to 3% range in recent quarters. The August real spending and income gains were net of 1.1% annualized inflation in the headline PCE price index, 1.6% annualized inflation in the core PCE price index, and 0.7% annualized inflation in the core PCE excluding housing. We’ve said a mouthful here, so let’s go back over each segment of the news in turn.

The gains in goods consumption were in accord with retail sales data released last week and showed decent growth for spending on goods other than cars and gasoline, but declines for the latter two. Similarly, services spending rose nicely, especially for services other than what we call the “Covid epicenter.” The epicenter sectors—health care, restaurants, lodging, travel, and entertainment—have generally languished in recent months after a period of strong growth following the Covid shutdown. However, for other service sectors, spending recovered earlier from the shutdown, but then decelerated in 2022 and 2023, only to pick up again this year.

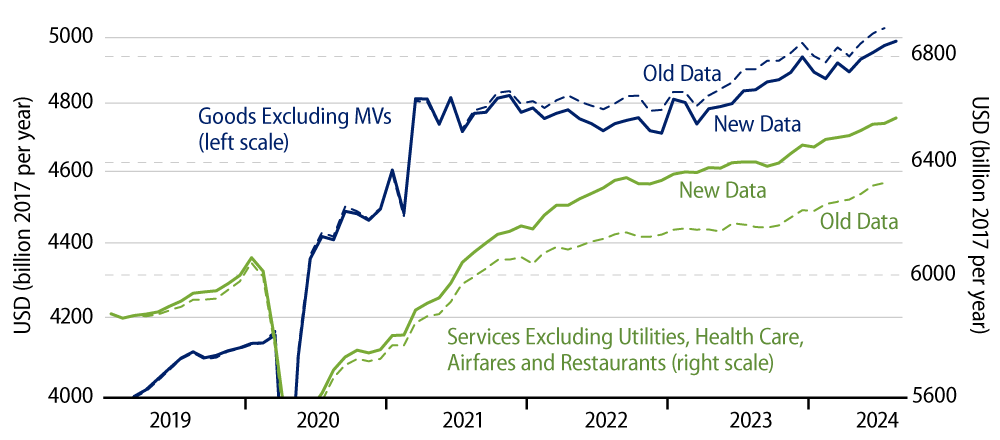

Concerning the benchmark revisions BEA announced today, as you can see in Exhibit 1, goods spending growth was revised down modestly in 2022 and 2023, while services spending growth was revised substantially higher in 2022 and 2023. And, yes, those upward revisions were mostly for services outside the Covid epicenter.

Notice also that spending growth in 2024 remains decent for both goods and services. Both are rising nicely this year following whatever “adjustments” consumers made in 2022 and 2023 that led to “pauses” in goods or services spending growth. This is a better outcome for 2024 consumption than we were expecting at the start of the year.

Revisions to the personal income data were curious. Personal income through July was revised upward by a hefty +3.3%, with stronger growth somewhat evenly distributed across 2021, 2022, and 2023. However, wage income was revised up by only +1.1%. Most of the upward revisions to income came in the form of employer pension contributions (+4.6%), proprietor incomes (+5.7%), rental income (+2.3%), interest and dividend income (+6.8%), and transfer payments (+4.6%). The latter were mostly in Medicare and veteran benefits.

It is odd that initial government estimates were off by so much for these categories. It is also odd that wage income was revised down in 2022 but up in 2023, so that all the net upward revision to wage income came in recent months. The oddity here is that the Labor Department has already announced substantial downward revisions forthcoming to payroll jobs over this same period. Upward revisions to income opposite downward revisions to payroll jobs don’t seem to match up. Oh well.

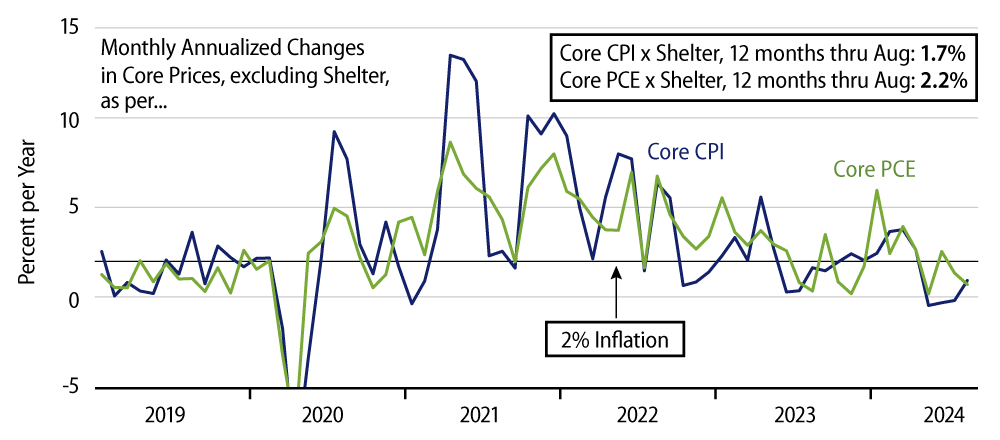

The PCE inflation news was favorable across the board, even more so than the Consumer Price Index inflation data released two weeks ago, as shown in Exhibit 2. The 1.1% annualized headline PCE inflation in August compares to 2.3% for the headline CPI, and 1.6% core PCE inflation compares to 3.4% for the core CPI. While much of this disparity is due to much higher weights of housing in the CPI than in the PCE, it is still the case that the 0.7% annualized rate in August for the core PCE ex housing compares to 1.0% for the corresponding CPI measure.

While the 2.2% rate for the core PCE ex housing over the last 12 months is still very slightly over the Fed’s target, this aggregate has averaged only 1.1% inflation rates over the last four months. This was likely an impetus to the Fed’s decision to cut short rates by 50 basis points (bps) last week. We stated then that current economic conditions were generally healthy, but the ongoing slowing trend in job growth might be worrisome, and the benign recent inflation experience might give the Fed cover to attempt to preempt further job market softening.

While we listed these possible drivers, we still thought the Fed would move cautiously and cut more modestly. Instead, they opted for a 50-bp cut. Do they see more worrisome signs in the data than we have recounted? And even if they do, given how long it has taken the economy to react to a 500-bp increase in short rates, will a 50-bp cut rather than a 25-bp cut in September make any significant difference? All good questions. We’ll try to divine the answers as new info arrives.