Private-sector nonfarm payroll jobs rose by 317,000 in September, with the August level revised upward by 107,000. Meanwhile, total nonfarm payroll jobs rose by just 194,000, impacted by a reported decline in public-school jobs.

The reported declines in school jobs are merely a continuation of the seasonal adjustment shenanigans that caused big reported gains in school jobs in previous months. Because so many schools are shuttered by Covid, “actual” school jobs don’t rise as much as usual in August and September, and they don’t fall as much as usual in June and July. These smaller-than-usual swings then get seasonally adjusted into big reported gains (in June and July) or losses (in August and September). This is a big reason why we typically ignore government jobs data and focus on private-sector payrolls. We think you should too.

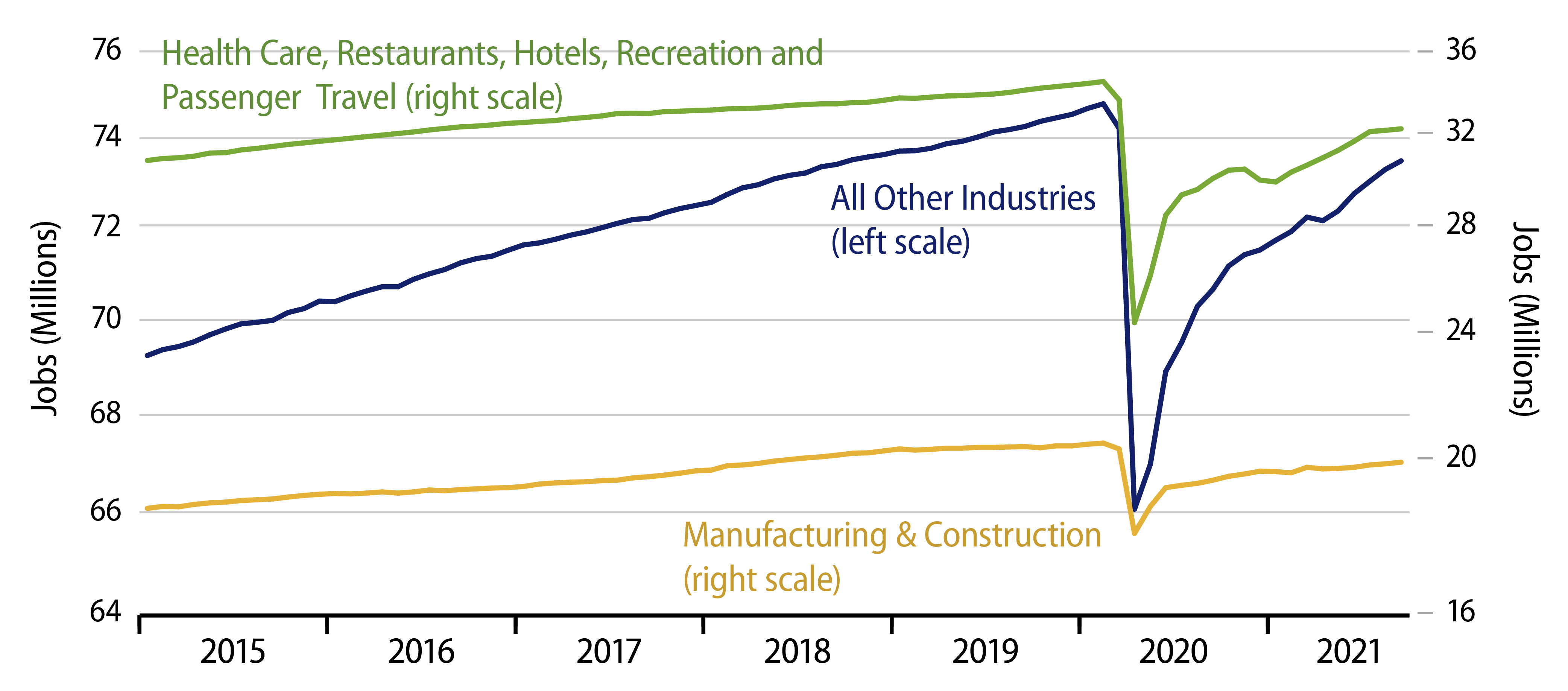

The reported gains in private-sector jobs would have been strong prior to Covid, but they are weak in the present context, when total payroll remains about 5 million jobs below the pre-Covid trend path. Why have payroll jobs disappointed expectations the last two months? The answer is simple. The recovery in the restaurant sector is complete, and ongoing Covid restrictions—as well as ongoing fears among the populace—have restrained growth in other service sectors.

From January through July, restaurants added 226,000 jobs per month on average. However, as those rapid gains upon reopening brought the industry back close to pre-Covid job levels and as various Covid-related issues have restrained further growth, restaurants have retreated to essentially zero job growth in the last two months.

Other service sectors, combined, gained an average of 349,000 per month from January through July. They averaged gains of 197,000 in August and September. This is a deceleration, and it could be attributed to the delta variant outbreak. Still, the slowing in restaurant job growth has been larger, and to us it appears to be more a reflection of a mostly complete recovery in the restaurant sector rather than an adverse reaction to the delta variant.

One other thing to consider is that every economic expansion since the 1980s has started with what economists called jobless recoveries. In all those expansions of the 1990s and after, output recovered faster than did employment.

In the present expansion, initial job gains were explosive, as workers who had been forcibly detained at home were suddenly allowed to return to work. With that wave past and with millions of potential workers mulling whether or not to return to work, while sales activity at various service sectors grow less than remarkably, further rapid job gains may prove harder to achieve than the markets have anticipated.