As usual on the first Friday of the month, our intention was to use today’s BTN (By The Numbers weekly economics blog post) to cover the September jobs data. However, the government shutdown has scuttled that release, so we’ll turn our attention to the benchmark revisions reported for GDP last week.

Once a year, the Commerce Department produces a comprehensive revision of the GDP data, usually going back about five years, with the revised data based on more complete information than was available in previous releases. The new data mostly cover the last 18+ months—in this case, from April 2023 to the present—but that new data also affects seasonal adjustments for previous data—in this case, back to 2019.

Now, the revisions to GDP announced last week were mostly a yawn, but they did present a substantially different picture of consumer spending for the present year. With respect to GDP, growth for 2024 was revised down by a very slight -0.1%. 1Q25 growth was revised down by -0.1% (annualized), while 2Q25 growth was revised up by +0.5%. While that last number sounds large, remember it is an annualization of one quarter’s growth, whereas the -0.1% for 2024 reflects growth over four quarters. In other words, growth over the last six quarters together was unchanged.

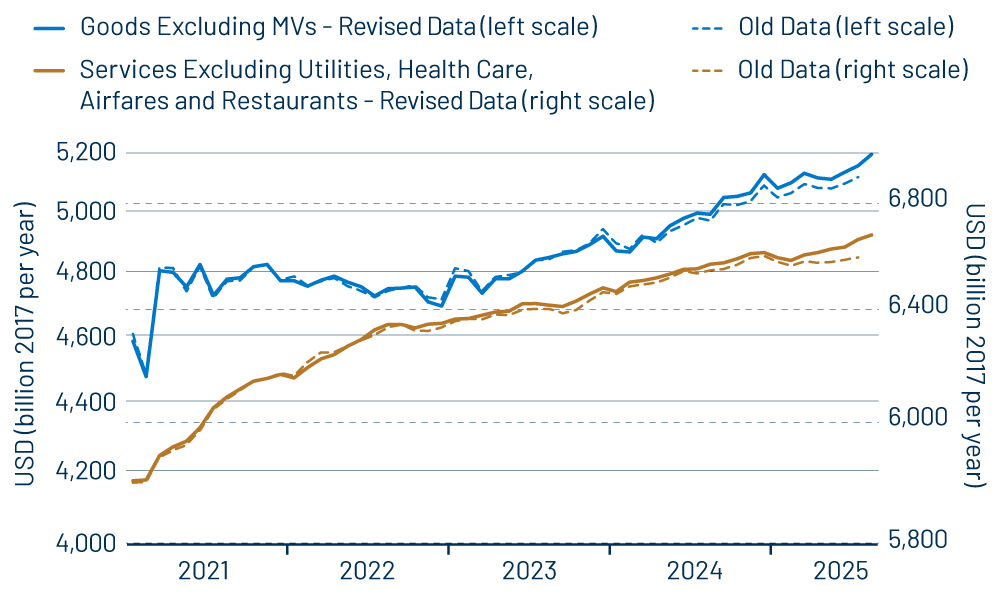

However, again, the upward revisions to consumer spending were substantial. Exhibit 1 shows data before and after the revisions for the “underlying” components of consumer spending we have tracked in these posts. (Motor vehicles are abstracted from within goods spending because of their wild swings when sales incentives are put on or removed. Similarly volatile items are excluded from services spending to derive a more stable, underlying series.).

Goods spending was looking pretty decent this year even before the revisions, thanks to the better retail sales data released for June-August. The revisions announced last week boosted goods spending a little higher. The revisions to services spending were more substantial. What had looked like zero or negative growth in services spending now, after the revisions, looks like steady growth at the same pace as was seen in 2024.

This solves a puzzle we had been dealing with in previous posts. We couldn’t come up with a reason why services spending should have gone flat this year. Growth in real personal incomes had been proceeding nicely all year, and if one were looking for the effects of tariffs on spending, one would expect to find it in goods spending, not in services spending, since the tariffs are mostly a factor for merchandise, not services. Yet, the previous data—through the August releases—had shown steady growth in goods spending and a marked slowing in services spending.

Last week’s releases squared this circle by revising away the services spending slowing. If you are skeptical of “suddenly” revised government data, given recent kerfuffle about replacement of government statisticians, etc., fair enough. We would just point out that 1) the revisions in question came from the Commerce Department, whereas the staffing replacements were in the Labor Department, 2) such swings are typical when benchmark revisions are announced and 3) as we have already reported, the revised spending data actually jibe better with other available data than did the pre-revisions spending numbers.

All in all, the GDP data paint a picture of very steady growth so far this year. We previously have questioned the accuracy of both the reported 1Q25 GDP decline and the robust 2Q25 gain, but these were not materially revised (currently -0.6% and 3.8%, respectively). The net of these two quarters comes to 1.6%, and we have seen forecasts of 3Q25 coming in around 3%, which would boost year-to-date (YTD) growth to about the same pace as in 2024. Again, pretty steady growth.

Similarly, consumer spending data indicate steady growth for both goods and services, as you can see in Exhibit 1. As already discussed, personal incomes have been growing comparably (2.3% per year in real terms YTD). Notice that the income growth has occurred despite a slowing in jobs growth.

Some analysts believe that we have yet to see the full effects of the tariffs. In this respect, it is perhaps worth noting that Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation data released last week showed renewed declines in goods prices in August, after these had risen in preceding months, apparently due to tariff effects. Also, if tariffs indeed have further negative effects in the months to come, those effects could be offset by renewed Federal Reserve easing.

To be sure, there are a lot of questions out there (including about the current shutdown), but this is nothing new. The data in hand paint a decent picture of the economy, and they make a lot more sense after the revisions than what we were seeing beforehand.