What’s Happening?

General elections in India officially kicked off on April 11 and will stretch out over six weeks in seven rounds of voting, with results expected to be announced on May 23. All 543 elected Members of Parliament (MPs) will be elected from single-member constituencies using the “first-pass-the-post” electoral system. The party with the simple majority of MPs (more than 271 seats), or the coalition that is formed to create a majority in the lower house of Parliament, or Lok Sabha, will select the next Prime Minister of India.

In the last general elections five years ago, Narendra Modi and his party, BJP, attained a simple majority in Lok Sabha, a feat that hadn’t been accomplished since 1984. Modi based his platform on being able to deliver on job growth and overcome bureaucratic inertia, both of which plagued the previous administration. Fast forward to today, BJP is not projected to win a simple majority and will likely have to rely on forming a coalition with some regional parties. While Modi has implemented sweeping reforms such as the goods and services tax (GST) and instituting a bankruptcy code for delinquent borrowers, critics have panned his administration as a failure with respect to demonetization, inflicting hardship on farmers and deteriorating employment prospects.

Possible Outcomes

The most recent polls have BJP winning the most seats in the elections, but it does not appear that BJP will be able to replicate the 2014 general elections wherein it secured the simple majority of seats without the support of any other party. The base case scenario is for BJP to win between 200 and 230 seats, in which case only a small coalition would be necessary to form a government. In this scenario, it is likely Modi will return as Prime Minister. However, in the unlikely event BJP underperforms and wins less than 200 seats but enough to form a coalition with several other regional parties, the chances of Modi continuing as Prime Minister is diminished as he has a poor reputation as a consensus builder. A candidate who has been rumored to be a potential replacement in this scenario is Nitin Gadkari, the current Minister for Road, Transport and Highways.

BJP’s biggest threat would be from the India National Congress (INC), led by Rahul Gandhi. While INC is unlikely to win sufficient seats to form the government, there still is a chance that a grand alliance with a number of regional parties could potentially win enough seats to supplant BJP and its coalition. However, we’d assign a low probability of this occurring. Finally, in the outlier of the scenarios, a small regional party could emerge as the kingmaker and install a relatively unknown politician as Prime Minister. This scenario would be the most disruptive to ascertaining on which policies the incoming government would focus.

Market Implications

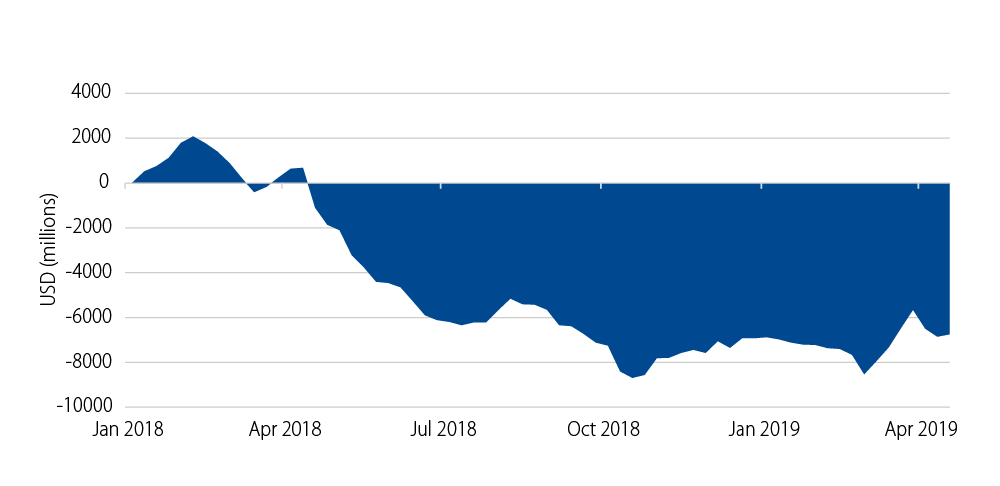

The base case scenario of BJP winning with Modi resuming Prime Ministerial duties would be the most favorable for markets. Currently, 10-year Indian Government Bond (IGB) yields trade at around 7.4% and have been in that range for the majority of 2019. At the same time, there has been a sustained divestment of India bonds by Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) since 1Q18 that hasn’t really recovered from its highs. Foreign utilization rates for India government and corporate bonds stand at 68% and 73%, respectively.

If political uncertainty is removed from the equation and Modi continues his policy of fiscal consolidation, then the expectation is for FPIs to reallocate into IGBs given India’s attractive carry. The Indian rupee should benefit from this inflow as well.

Even in the event that BJP forms the government with a larger coalition, or INC forms the government, we believe the risk of yields making a sharp move up are low. Economic policy isn’t likely to deviate drastically from what we have seen in recent history. The Reserve Bank of India’s recent dovish tilt has helped equity inflows and if the Indian government continues to stress growth, the rupee looks to be supported. The outlier scenario here is that a small regional party is able to place its candidate into power. In that case, we believe the potential for a sharp selloff in both the currency and the bond market is high.

Investment Strategy

From a macroeconomic perspective, we are constructive on India. While its current account is likely to remain in a deficit, India’s overall balance of payments will be well supported. Foreign direct investment continues to be strong to the tune of nearly USD 3 billion per month while foreign portfolio flows are likely to resume once base case election results are finalized. RBI has accumulated a significant amount of FX reserves, north of USD 410 billion, to neutralize external shocks. Furthermore, in 2019 RBI eased key policy rates by 50 bps in an effort to bolster growth as headline inflation has remained at the lower end of RBI’s 2% to 6% inflation target band (4% target). Shaktikanta Das was appointed as RBI Governor in December 2018, following the abrupt resignation of his predecessor, Urjit Patel. Governor Das is viewed by the market as someone who is closely aligned with government policy. However, this has led to some concerns as to the independence and autonomy of RBI.

We maintain an overweight in Indian bonds heading into this long election cycle. In the months leading up to the election we have added duration as the spread between the 3- and 10-year IGBs widened to over 50 bps. We also find value in short-dated quasi-sovereign paper which has a pickup of roughly 80 to 90 bps against IGBs. However, given the binary risk of the election outcomes, we prefer to hold off on adding either more India bond or FX risk.