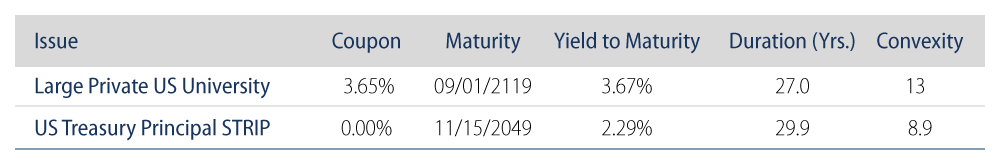

Are we about to witness a new generation of bond issuance that will take a full century to mature? The concept of a bond that matures in 100 years is challenging for many US investors to comprehend, with perhaps the exception of life insurers. Until the last few years, the number of fixed-income securities in the US with maturities longer than 30 years has been limited, prompting many institutional investors with long time horizons to allocate elsewhere. However, the low interest rate environment since the financial crisis has prompted a number of high quality universities, hospitals and corporations to issue “ultra-long” bonds, with maturities of 50-100 years. For example, last month we saw a taxable bond issued with ratings of Aa3/AA- (Moody’s/S&P) and a maturity date in 2119.

While insurers fret about low rates and the flat shape of the yield curve, ultra-long issuance may actually be a boon for some life insurers. New ultra-long issues may offer the following benefits:

- Attractive regulatory capital charge: Issues are typically investment-grade rated (NAIC 1 and 2) so they have a lower risk-based capital charge.

- Higher yield than US Treasury (UST) STRIPS: Ultra-long issues would offer yields higher than typical UST STRIPS.

- Familiarity: Issuers are those that most US life insurers are already familiar with due to large muni and corporate general account portfolios.

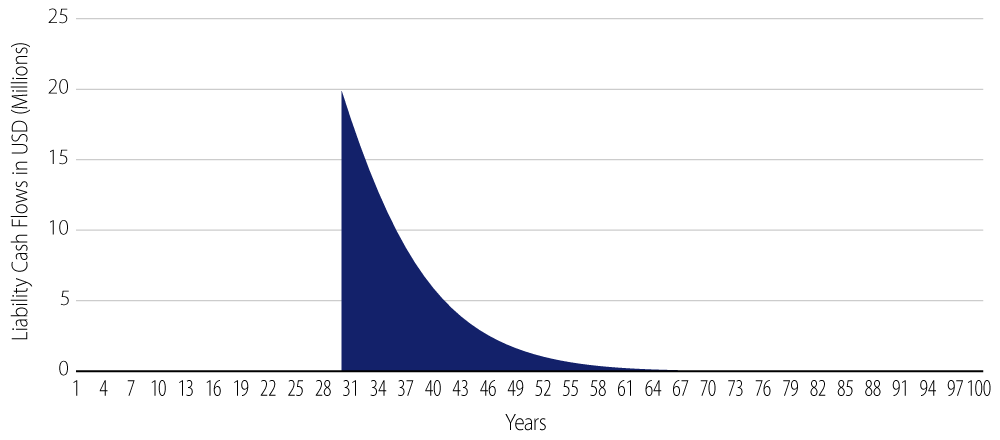

- Convexity: The higher convexity of these bonds could help to hedge long-dated insurance business lines, such as long-term care policies. Using a sample long-dated liability cash flow stream, you see large cash flows that go past the traditional 30-year bond issue window. While only representing 4% of present market value, our analysis suggests a combination of 100-year securities, and UST STRIPS does a better job hedging the sample cash flows past 30 years than does a STRIP alone.

It remains to be seen if ultra-long bond issuance will continue to gain steam in the US. In fact, the US Department of the Treasury is currently researching the topic to determine if it will issue ultra-long bonds itself. The Treasury solicited feedback from market participants this August, as it also did so in 2017. No determination has yet been made but if ultra-long issues from the government and private issuers do become more commonplace, it may be a silver lining for life insurers in today’s low rate environment.