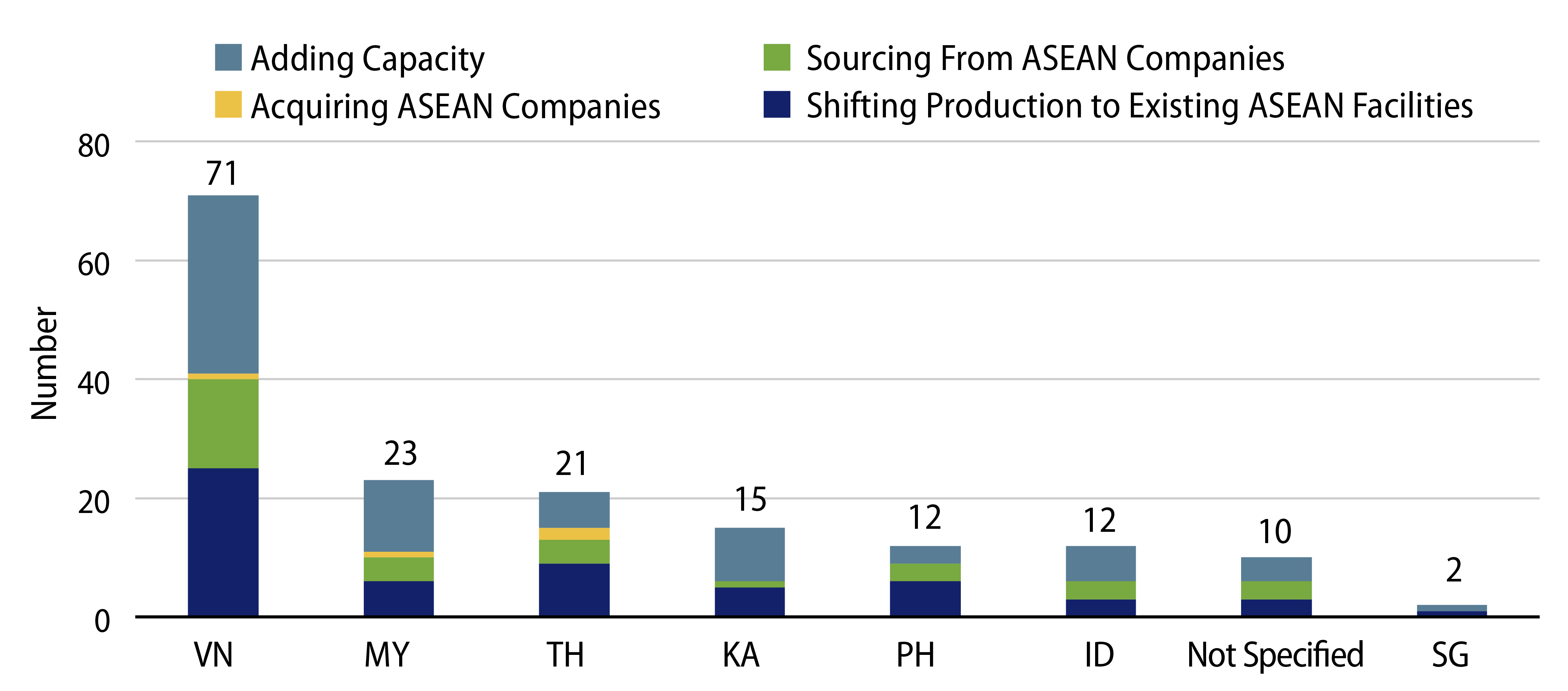

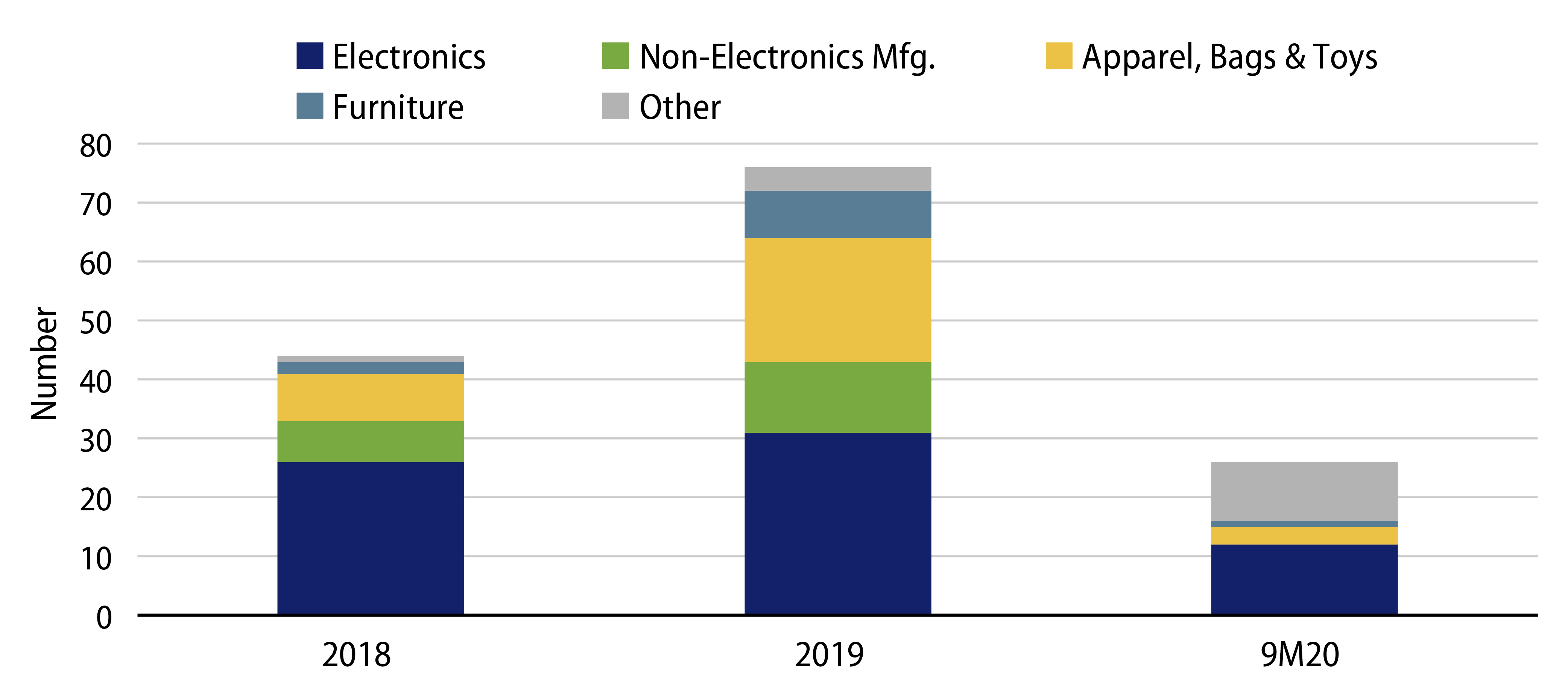

Understanding the evolution of global supply chains can help investors make better informed decisions. In this post, we explore continuing shifts in Asia supply chains in the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though the “Phase One” trade deal had been forged between the US and China in late 2019, a lasting resolution to the strategic rivalry between the world’s two largest economic powers is not in the cards. Indeed, there are multiple fronts to the superpowers’ rivalry—these include trade, technology and finance. In Asia, China+1 supply chain shifts were in progress for some time due to higher and rising labour costs in China. Trade tariffs from the Trump administration have intensified the process and prompted companies using China as their main manufacturing base to further develop their China+1 strategy by primarily diversifying into ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Exhibit 1). This was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic; however, we expect supply chain shifts to deepen post economic reopening with capacity additions being the main mode of entry (Exhibit 2), even as China’s exports have recovered strongly following successful pandemic control.

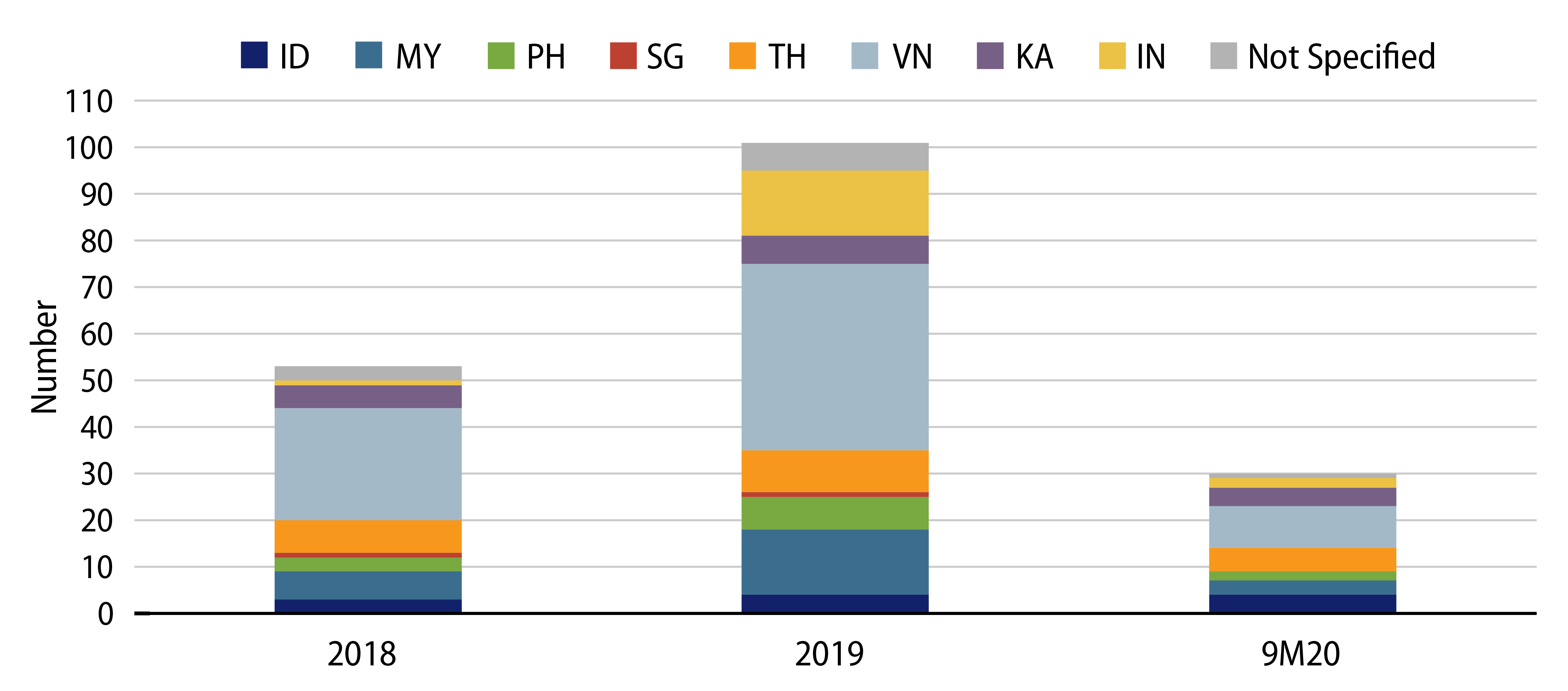

Supply chain shifts in Asia have been developing both within geographies and also across sectors. For example, amidst the large drop in supply chain shift announcements into the region during the initial COVID-19 outbreak last year, relocation announcements to Indonesia from China increased and relocations from South Korea (LG Electronics) and Japan (Denso) were planned. While Vietnam remains the preferred destination for relocation, its share of new announcements has fallen to 29% (2019: 40%), with the mix of investors expanding from China + HK and US companies to European companies. Although electronics manufacturing still dominates relocation plans, the share of “other products,” including lifestyle products, precision metals and tires surged (Exhibit 3). Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan were the biggest beneficiaries of trade diversion in 2018-2019, and remained so in 2020.

In addition to the impact from tariffs and the long-term risks associated with the rivalry between the US and China, the Covid pandemic has highlighted another key challenge, which is having heavily concentrated supply networks. Those issues relate to security concerns of being overly dependent on another nation for critical deliveries of medical supplies and technology. In a sense, “just in time” intermediate inputs for global manufacturing are now evolving to “just in case” inventory stocking. As such, the Biden administration has ordered a global supply chain review for microchips as well as large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals, critical minerals and strategic materials such as rare earth metals. Most US microchips come from Taiwan and South Korea, and the US gets almost all of its rare earth metals from China. Additionally, we believe the Biden administration will continue to treat China as a “strategic competitor.” Although, unlike under the Trump administration, trade policies are now expected to be more thoughtful, process-driven and multi-lateral. US-China tensions will be more focused on key technology export curbs and national security concerns rather than directly aiming to use trade tariffs to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US.

RCEP Could Promote and Deepen Supply Chain Diversification Within the Region

While the expansion of the China + 1 supply network is being developed by Western multinationals, the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) is aiming to deepen integration within the region and highlights a more inward-looking shift of regional supply networks and production. The successful conclusion of RCEP, comprising 10 ASEAN members and key partners Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand—which account for 30% of the world's economy and one-third of its population—was a major step forward for the region at a time when multilateralism is losing ground and global growth is slowing. This signals the region’s collective commitment to maintaining open and connected supply chains and promoting freer trade and closer interdependence.

RCEP can promote foreign direct investment (FDI) by: a) improving market access (e.g., via removal of conditional performance requirements), b) granting most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment to RCEP members and c) strengthening the intellectual property rights framework. RCEP facilitates intra-regional trade by lowering transaction costs, which will encourage companies to source more inputs and produce more within RCEP. Costs are lowered as a result of eliminating most tariffs, simplifying customs procedures and establishing a common Rule of Origin (ROO). Despite China’s scale and scope as a production base, lower barriers to trade could increase ASEAN’s attractiveness as an alternative production hub for exports, given the latter’s lower costs and continued tension between the US and China. Based on the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ estimates, the APAC region could see its annual exports in 2030 increase by $500 billion, with larger gains for China ($244 billion), Japan ($133 billion) and Korea ($64 billion)—considering that these economies make up 80% of RCEP’s GDP, and are not joint members of any other foreign trade associations (FTAs).

RCEP Gains Could Be Complemented by Domestic Reforms That Reduce Barriers to FDI

Indonesia’s Omnibus Law is a prime example of how gains from RCEP could be complemented at the national level by domestic reforms that reduce barriers to FDI. Broadly, the law aims to reduce policy uncertainties, improve the business environment (e.g., by simplifying licensing requirements), and provide regulatory frameworks for investments into new industries. The Omnibus Law could complement RCEP in reducing non-tariff measures and increasing the export-orientation of Indonesia’s manufacturing sector. Opening up the economy to more export-oriented FDI would not only sustain higher than 5% domestic demand growth, it would improve Indonesia’s low global value chain (GVC) integration and reduce structural vulnerability to periodic balance of payment (BOP) crises. That said, in the early stages, this would require greater policymaker acceptance of intermediate imports necessary for the production of exports, as opposed to pushing for greater import substitutions.

Investment Implications

Western Asset’s Asia Investment Team uses these insights on Asia’s supply chain shifts to help plot the longer-term economic trajectory of the region’s heterogenous economies to optimize our investment decisions. The developments highlighted here strengthen our belief that the region as a whole is likely to maintain its edge in the global supply networks, both in terms of costs and also through its available infrastructure. Importantly, trade pacts and supply chain shifts should not be seen as a zero-sum game but may be a mutually beneficial development for the region (e.g., a lower cost of production and higher quality products).