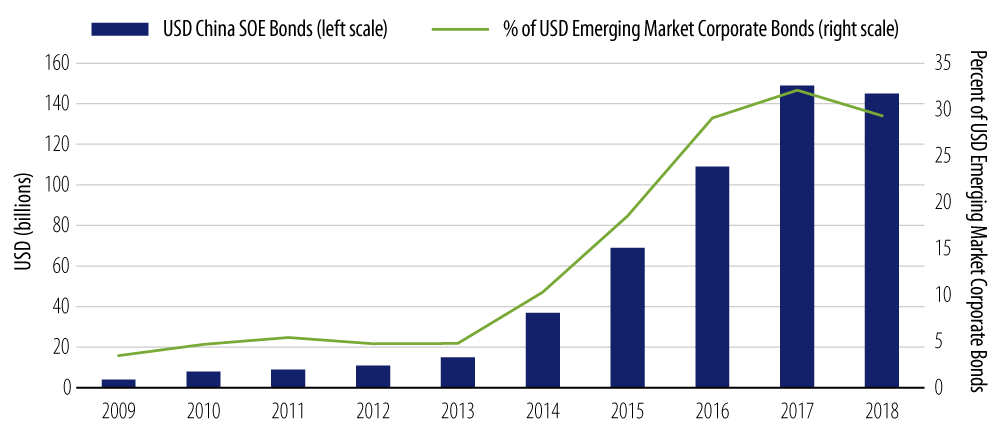

Offshore debt issuance by Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) has witnessed a phenomenal rise, making it too significant to ignore. Over the past decade, USD-denominated debt issued by the country’s SOEs has increased by more than 10-fold, reaching a market capitalization of $145 billion. The expansion has been driven by overseas M&A transactions, a desire to diversify funding sources, as well as the lower cost of funding. The scope of business for these SOEs spans major sectors, including resources (energy and metals & mining), infrastructure (transportation and utilities) and others (food and property). Given the dominance of the state’s hand in steering economic policies, SOEs are therefore intertwined with the country’s macro cycle.

With more new entrants in the offshore debt market, the concept of what constitutes an SOE has inadvertently become more elusive. Historically, Chinese SOE debt issuers are comprised almost exclusively of strategic national entities that are 100%-owned by the central government. Apart from policy banks, these companies include oil firms (e.g., China National Petroleum Corporation and China Petrochemical Corporation) and utilities (e.g., State Grid Corporation of China). Over time, however, ties to the state have evolved into a spectrum of varying official support, reflecting unique standalone features among first-time SOE issuers. These differences include the magnitude of influence (100%, majority or partially owned), the type of owner (central government, agency or local), as well as the structure of security (direct issuance, onshore parent guarantee or keepwell undertaking).

All else being equal, the importance of bottom-up analysis cannot be overstated, particularly for SOE credits without systemic significance at the national level. While none of the Chinese SOE bonds have an explicit government guarantee, most if not all Chinese SOEs receive direct or implicit backing. This is often reflected in the multiple-notch uplift on their standalone credit ratings. Despite a widely held belief of sovereign backstop in times of financial stress, we believe the extent and timeliness of state support can vary considerably across SOEs. The Qinghai Provincial Investment Group, which failed to make a timely coupon payment earlier this year, provides a case in point. Two decades ago, at the height of the Asian financial crisis, an investment trust company in China wholly owned by provincial government defaulted on its offshore debt.

Given ongoing reforms that will subject SOEs to greater market scrutiny, credit differentiation will most definitely gain traction going forward. We remain wary of exposure to peripheral SOE credits in non-strategic competitive sectors, such as property and metals & mining. We would also steer clear of companies with minimal publicly available information, as this exposes the investor to “black hole” risk. On the other hand, core SOEs can serve as an appealing proposition for the global investor seeking high-quality diversification outside of developed markets. Our expectation is that large central SOEs with strong financial metrics should stay resilient through the full business cycle, and are less susceptible to a further escalation in the US-China trade spat given their large domestic-oriented operations. Valuation-wise, top-notch A+ rated credits are attractive in the context of the current low-rate, yield-starved environment. To illustrate, Chinese oil SOEs compare favorably, currently trading 30-40 bps wide of DM peers such as British Petroleum and ConocoPhillips.