The Commerce Department today reported that real GDP grew at a 3.0% annualized rate in 2Q25. This follows and reverses a reported -0.5% rate of decline in 1Q25. The GDP price index showed a 2.0% annualized rate of inflation in 2Q, while the price index for core consumer spending showed a 2.5% annualized rate of increase.

It is no accident that 2Q GDP showed a relatively rapid gain that offset and reversed the 1Q decline. Back in our May 2 blog post, we speculated that the reported 1Q GDP decline was a statistical fluke that would be reversed in 2Q, and today’s data confirm this assertion. Here is what is going on beneath these numbers.

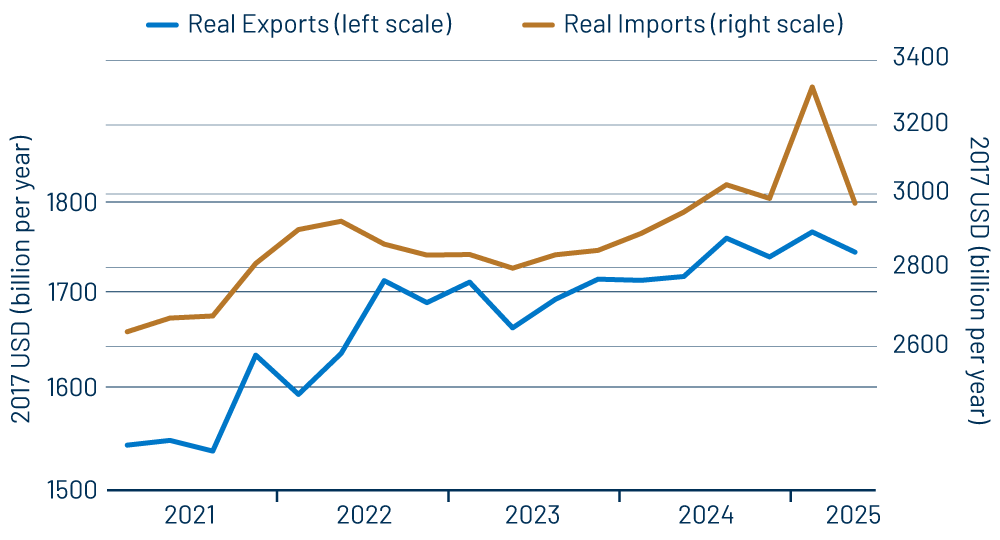

As reflected in Exhibit 1, in 1Q, merchants foreign and domestic front-loaded shipments of foreign goods into the states in order to ''beat'' the imposition of tariffs in 2Q and after. Imports then fell back to more normal levels in 2Q, with tariffs mostly in place. Imports enter GDP negatively, so the import surge served to reduce reported 1Q GDP and stoke reported 2Q GDP.

There is no question that the import swings actually occurred. We think the 1Q decline and big 2Q gain are bogus—statistical artifacts—because the imported goods go somewhere, and government data collection techniques are not as accurate in measuring the uses of imported goods as they are measuring the imports themselves. That is, goods imported into the US are either consumed by households and businesses or else added to domestic inventories.

Imports themselves are subject to direct tracking by the Customs Bureau, so the import data within GDP are essentially exact. However, the uses of imported goods by consumers and businesses and the additions to inventories via these goods are measured only indirectly, via surveys of merchants. And when there is an unprecedentedly large surge in imports, such as happened in 1Q, it is only to be expected that the reported usages of said imports will not be as accurately reported within the GDP data as are imports themselves. This happened in 1Q, and said swings were reversed in 2Q.

Now, it is certainly possible that a surge in imports in 1Q led to a decline in domestic output of similar goods. This is what the GDP data say happened in 1Q. However, direct measures of domestic goods production—such as the Federal Reserve’s industrial production data—show a solid gain in output in 1Q and slower output growth in 2Q. In contrast, the GDP data report a -0.8% decline in ''goods GDP'' in 1Q and a 9.2% rate of growth in 2Q. Again, our take is that both these swings are statistical artifacts driven by the swings in imports, and that the actual economy experienced growth in goods production in both quarters of 2025 so far.

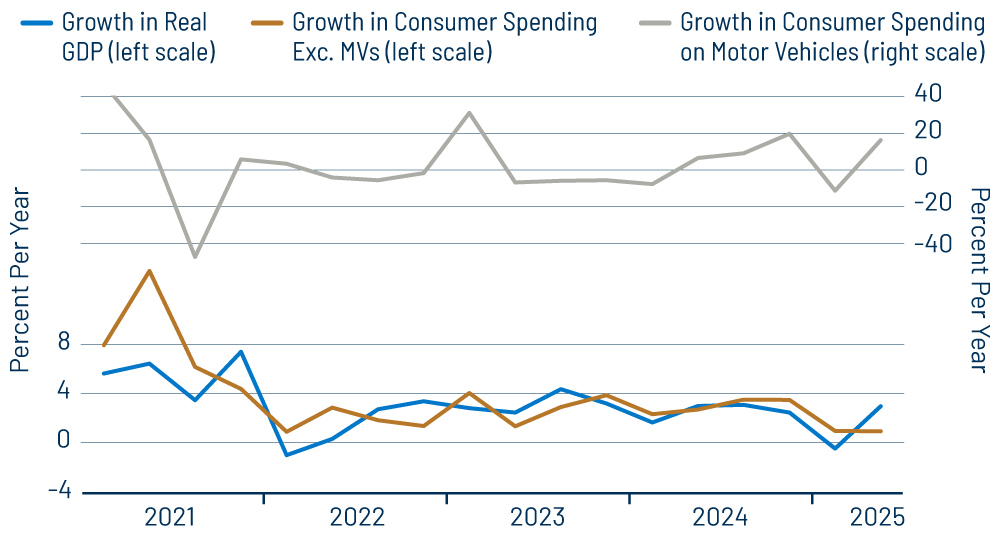

Combine the 1Q and 2Q reported GDP swings and the result is 1.2% average annualized growth in 1H25. This is a slowing from the 2.5% average growth currently reported for 2024 and is due to slower growth in consumer spending. Exhibit 2 contrasts the reported swings in real GDP growth with those in consumer spending.

As seen there, underneath the wild swings in reported GDP, growth in ''underlying'' consumer spending (i.e., spending net of motor vehicles) slowed in both 1Q25 and 2Q25. Yes, growth in total consumer spending in 2Q was lifted by a bounce in motor vehicle purchases, but that merely reversed a decline in 1Q. Vehicle spending typically bounces around, and recent months were no exception.

Beneath the vehicle spending noise, consumption growth was softer in both 1Q and 2Q. It is tempting to blame this on the tariffs, but tariffs would not be expected to affect service prices or services spending, and growth in real services consumption was especially slow in both 1Q and 2Q despite markedly slower services inflation.

The bottom line is that headline GDP growth data are distorted in both 1Q and 2Q. Those lamenting a 1Q decline now have to do an about-face and herald a 2Q rebound, while those pointing out the distortions in 1Q data have to be equally circumspect about the reported 2Q bounce. The reality is that growth has been pretty steady in both quarters of 2025 so far, but at a slower pace than in 2024, thanks to softer growth in consumer spending.

Our guess is that the wild swings in imports will not be repeated in the second half of the year. Meanwhile, slow consumer spending growth has occurred despite mostly stable job growth and decent gains in personal income in both 1Q and 2Q. The question is whether the soft first half gains in consumer spending were ephemeral or an emerging trend. Our guess is the former, but that is the big question for the economy going forward.