KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Western Asset integrates ESG considerations into our analysis of investment-grade, high-yield and bank loan corporate issuers, as well as sovereign and corporate issuers in both EM and frontier markets, seeking to identify otherwise mispriced investment opportunities.

- While macroeconomic metrics paint an attractive picture of Indonesia, limiting one’s analysis to such traditional measures excludes factors unique and relevant to Indonesia’s credit profile.

- We apply the Western Asset sovereign ESG framework as a guide to evaluating non-financial elements, including our assessment of the country’s performance in each ESG area.

- Indonesia has made noteworthy progress on reducing income inequality and improving law enforcement, but continues to face significant and persistent challenges in a number of ESG areas, including corruption, GHG emissions, gender imbalances and external food dependency.

- We will continue to monitor developments across the areas of concern and engage with government officials, multilateral banks and non-governmental organizations as appropriate.

At Western Asset, environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysis plays an essential role in our search for long-term fundamental value investments, as we believe that material ESG factors can affect an issuer’s risk profile. By integrating ESG considerations into our analysis of investment-grade, high-yield and bank loan corporate issuers, as well as sovereign and corporate issuers in both emerging market (EM) and frontier markets, we seek to identify investment opportunities that would otherwise be mispriced.

Our previous piece, ESG Investing in Sovereigns: Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities, focused on how ESG can complement the financial and macroeconomic components of sovereign analysis. In that paper, we explained how ESG factors can significantly affect a sovereign’s path for economic growth. We also introduced our framework for sovereign ESG analysis, highlighting the key environmental and social factors we consider and their nexus with governance. Building upon our prior work, here we outline our views on Indonesia to illustrate how a focus on ESG principles can complement traditional sovereign credit analysis.

The Macroeconomic Landscape

Macroeconomic metrics paint an attractive picture of Indonesia. Despite global headwinds, GDP growth trended higher over the past four quarters to 5.17% year-over-year (YoY) in 3Q18. Meanwhile, government debt has remained at relatively low levels, measuring 29.9% of GDP in 2018. Inflation has also been well managed, with Indonesia’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) steadily falling throughout 2018 to conclude at 3.13% YoY—a significant achievement for an economy that just a few years ago experienced persistent inflation of 7% to 8%. As a result, Indonesia’s central bank, Bank Indonesia, is highly regarded by foreign investors for its prudence in managing monetary policy. Over the past two years, all three international credit ratings agencies have taken notice as well by upgrading Indonesia’s credit rating, led by S&P (BBB- from BB+) and closely followed by Moody’s and Fitch (up one notch each to Baa2 and BBB, respectively).

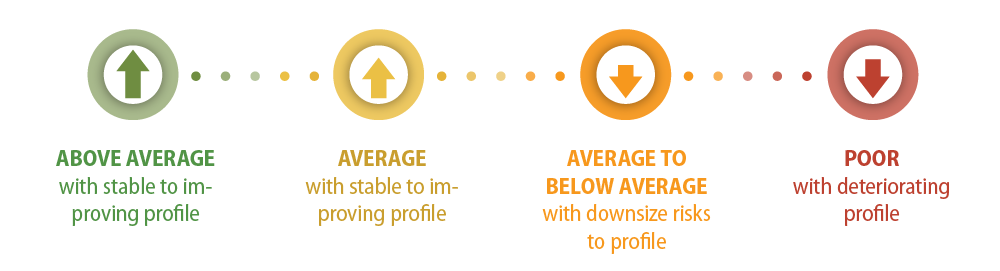

However, limiting one’s analysis purely to traditional measures such as these fails to identify a number of factors unique and relevant to Indonesia’s credit profile. In the following analysis, we apply our previously introduced sovereign ESG framework (Exhibit 1) as a guide to evaluating these non-financial elements, including a color-coded symbol to represent our assessment of the country’s performance in each area (Exhibit 2).

Environmental: Making Progress on Challenges

![]() Water

Water

With a rainy season that spans seven months of the year, Indonesia has no dearth of water. Its water accounts for 21% of the Asia-Pacific region’s supply, and almost 6% of the world’s. By 2015, water access was relatively high as well; 85% of Indonesia’s drinking water sources were classified as “improved” by the World Health Organization (i.e., water that is piped into a communal area or directly into a dwelling), and 84% of the population had access to such sources. As one of its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) initiatives, Indonesia has pledged to increase access to improved water sources to 100% by 2019.

The country’s major water-related concerns revolve around sanitation, pollution and land subsidence. In 2015, only 59% of the population had access to improved sanitation facilities (defined as those separating human excreta from human contact). As with water source improvement, the government has an ambitious plan to roll out improved sanitation access to 100% of the population by 2019. Pollution of waterways has gone hand-in-hand with poor sanitation management and lax regulatory oversight. With large swaths of the population still reliant on natural water sources for irrigation and hygiene, Indonesia plans on revoking business permits, installing CCTV cameras to monitor activity and using dredging instruments to gradually rehabilitate major waterways. Another water-related issue is the excessive use of groundwater for everyday purposes and for drinking by those who do not have access to piped water or cannot afford expensive bottled water. Illegal pumping of groundwater in Jakarta, Indonesia’s largest city, has contributed to its rapid rate of land subsidence, which is the fastest in the world. Some parts of Jakarta have been documented as sinking at an alarming rate of 25 centimeters per year.

![]() Food

Food

Given its warm climate and ample rainfall, one might assume that Indonesia has minimal, if any, concerns around producing food for its residents. Indeed, it is the third largest rice producer in the world. Yet, Indonesia ranks poorly in The Economist’s Global Food Security Index, placing 69th out of 113 countries. Even though its rice fields routinely produce more tons than the country consumes, Indonesia is a net importer of rice, purchasing two million tons from other countries in 2018. Domestic rice prices, which have risen due to inefficient farming techniques and a declining amount of farmable land, now stand at over double the international standard price. Government policies to increase rice production have been largely ineffective at reducing the country’s import needs and have been criticized for further exacerbating income inequality issues, which will be discussed later in this piece.

![]() Energy

Energy

Endowed with a rich natural resource base, Indonesia is self-sufficient from an energy perspective. It provides access to electricity to 100% of its urban and 94.8% of its rural population, which is superior to many of its East Asian and Pacific peers despite its lower income per capita. The state-owned enterprise Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) transmits and distributes electricity to almost the entire country, which has enabled it to increase electricity access overall from just 61.7% in 1990 to its current level of 97.6%.

In addition to substantial coal and natural gas reserves, Indonesia also has 60 oil basins, only 22 of which have been tapped and drilled. Nevertheless, Indonesia has taken a proactive approach to energy management, with a goal for renewables to generate 23% of its power by 2025. It plans for this energy to come from a variety of sources, including hydropower, biofuel, geothermal, wind and solar.

![]() Emissions and Environment

Emissions and Environment

With rainforests and verdant greenery accenting its landscape, Indonesia is sometimes referred to as the “Emerald of the Equator.” But while the country’s abundant natural resources enable it to maintain energy independence, they have also negatively impacted public health through their impact on the environment. Coal, which produces significantly more carbon emissions than other fossil fuels, provided over half of Indonesia’s power generation in 2016. Farmers have also created pollution by “slashing and burning” to clear harvested crops from lands before replanting. These practices in combination with drought conditions resulted in the “haze crisis” of 2015 that plagued the entire Southeast Asia region. Recognizing the severity and urgency of the situation, Indonesia pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 29% between 2015 and 2030, in part through diversification toward renewables and a reduction in deforestation.

Progress is being made; in 2006, Indonesia was the world’s fourth largest emitter of GHG. By 2012, Indonesia improved its ranking to 10th. It is still too early to declare victory, however, as Indonesia remains reliant on fossil fuels and is still the fifth largest coal producer in the world, behind China, the US, Australia and India.

Another ongoing concern is the deforestation and damage caused by palm oil and timber developers. Encouragingly, Indonesia imposed a moratorium on national peat drainage in 2016, which slowed down the loss of tree cover by 60% the following year, but disruptive development remains ongoing in over 25% of the country’s peatland.

Social: Unlocking the Growth Potential

![]() Demographics and Group Cohesion

Demographics and Group Cohesion

Indonesia has a favorable demographic profile; the country’s population is the fourth largest in the world, relatively youthful with a median age of 28 years old, and expected to grow at a healthy rate of 0.9% over the next five years. Indonesia also has a large working-age component and its current dependency ratio of 48.5% is its lowest on record.

Indonesia is home to numerous indigenous people, with 101 groups identified in the 2000 census, and predominantly Muslim (87% of the population). Ethnic Chinese and Malay constitute small minorities within the country. The country is relatively unified by an Indonesian national identity, and no violent ethnic conflicts have occurred since the turn of the century.

Although the country is generally peaceful and tolerant, local Islam extremist groups have long existed. In recent years, they have accelerated their efforts and shifted their target from foreigners to Indonesian Christians and the government. 16 acts of terrorism have occurred since 2011, with four incidents occurring in both 2017 and 2018. In addition, the front lines of the movement have expanded to involve women (and even children at times), an unexpected development in a society where women have long played a supporting role, as we will discuss in the next section.

![]() Labor Market

Labor Market

Indonesia’s labor market has been healthy, with unemployment falling from 6.2% in 2013 to 5.1% by mid-2018. However, severe gender imbalances exist, as the rights and opinions of Indonesian women have historically been regarded as secondary to those of men. Archaic beliefs such as needing a male to serve as the sole breadwinner in a household still remain entrenched across the country, which oftentimes limits a woman’s educational and career opportunities. In 2017, the United Nations Development Program assigned a Gender Inequality Index (GII) score of 0.453 to Indonesia, ranking it 104 out of 160 countries on measures of female reproductive health, empowerment and economic activity. This discrimination is mirrored in employment trends, as only 50.7% of eligible women participate in the workforce, compared with 81.8% of eligible men. Similarly, women hold only 19.8% of Parliament seats in Indonesia. That stated, Indonesia had a female President between 2001 and 2004, Megawati Sukarnoputri, who was Vice President to President Abdurrahman Wahid and succeeded him when he was removed from office. Small signs that politicians are ready to address gender inequality are emerging. Leading up to this year’s general elections, incumbent President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, has made some overtures to include women’s rights as a part of his platform. While increased awareness and discussion are most welcome, Indonesia must translate these into implementation.

![]() Equity—Income Dispersion

Equity—Income Dispersion

Indonesia’s economy has expanded at a strong pace, with an annual growth rate of 5.6% since 2000, but the benefits have spread unevenly. Today, the cumulative net worth of the four wealthiest Indonesians exceeds that of the poorest 100 million combined, many of whom reside in rural areas. The rise in income inequality in Indonesia (as measured by the Gini coefficient, which increased from 30 in 2000 to 41 in 2013) was the second highest among Asian countries, behind only China. Groups with lower incomes have been particularly affected by the rise in rice prices that we discussed earlier in this paper. While we have a positive view on Indonesia’s other social factors, the gap between the rich and the poor presents some downside risk to the country’s growth potential.

In recognition of this risk, the Indonesian government has made a concerted effort to reduce income inequality. Over the past two decades, it has steadily increased spending on education, health and microfinance programs for the poor, and invested in infrastructure to improve connectivity and communication between rural and urban areas. As a result, the national poverty rate has fallen from 15.4% in 2008 to 9.8% in 2018. This year, the National Development Planning Ministry seeks a further drop in poverty to 8.5% to 9.5%.

![]() Equity—Corruption

Equity—Corruption

As with many developing countries, corruption is particularly problematic in Indonesia, which ranks 89th out of 180 countries according to Transparency International. Indonesia’s practices, however, have slowly improved due in large part to prosecutorial efforts by the anti-corruption commission created in 2004, the Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK). The KPK has achieved an almost 100% conviction rate since its inception, resulting in the sentencing of 122 parliamentarians, 25 ministers, 17 governors, and 51 regents and mayors. These efforts have reduced political corruption, but it remains endemic. Bureaucratic corruption also remains an issue despite the country’s efforts to enforce and streamline regulatory processes.

Governance: Room for Improvement

![]() Political Structure

Political Structure

From 1966 to 1998, Indonesia’s political climate was marked by strife and economic hardship under the guardianship of an authoritarian government. In 1998, President Suharto was ousted from power, beginning a political phase now referred to as Reformasi. The military, once dominant under Suharto, was moved to the sidelines and replaced with a democratic, multi-party system, which enabled Indonesia to develop a functioning business environment and draw private investment, in particular to the manufacturing sector. Today, the Indonesian parliamentary system is bicameral, with the President serving as head of both state and government. The judicial branch maintains checks and balances on both branches. Currently, no one party holds a dominant share of parliament; the Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) holds the largest share at 19.5%. Given the challenges of building a consensus-driven coalition, forming a government in Indonesia generally is not an easy task.

One of the major changes under Reformasi was the decentralization of government functions. This gave local municipalities the authority to make self-directed changes in a myriad of sectors including healthcare, education, agriculture and manufacturing. The purpose was to make the government more responsive and adaptable in a country that is not only one of the most populous in the world, but also one of the most diverse. Before decentralization, receiving permission from the provincial government for municipal decisions was not only time consuming, as the province in turn needed to contact the central government, but also expensive as bribery was often necessary to facilitate any request. While decentralization was well-intentioned, however, municipalities at that time often lacked the expertise to carry out sectoral reforms and at present day we observe that bureaucratic inefficiencies have largely moved from the provincial level down to the municipal level.

![]() Political Capacity

Political Capacity

An examination of the presidential office sheds light not only on political capacity but also on the feedback loop between social and governance factors in Indonesia. In 2014, President Jokowi’s “man of the people” image and populist platform helped him to defeat candidate Prabowo Subianto, a former special forces commander alleged to have committed serious human rights crimes against pro-democracy activists in the pre-Reformasi period. Subianto has returned for the 2018 election, this time seeking to appeal to voters on several of the environmental and social issues previously touched upon, for example, decreasing food dependency through import-substitution policies, reducing GHG emissions through higher utilization of renewable energy, and cutting tax rates to address income inequality and encourage foreign direct investment. Both candidates have emphasized their commitment to reducing corruption and have catered to Muslims (the majority voting bloc) through their chosen running mates and pointed rhetoric. We will watch this April’s election closely for indications of future shifts in the social and economic landscape.

![]() Institutional Framework

Institutional Framework

Since the beginning of Reformasi, battling corruption has been at the forefront of every presidential campaign. President Jokowi was elected on an anti-corruption platform and in 2016 introduced a legislative package to create a “culture of law” and empower officials to enforce anti-corruption regulations. Part of this drive was to further support KPK. Recently, KPK leaders have been victims of both acid and bomb attacks. While these were horrible events, it could be perceived that the attacks were driven by the KPK hitting its marks. Notwithstanding Indonesia’s progress in easing foreign investment, there hasn’t been much recent innovation in the fight against corruption, and we continue to regard corruption as a risk of doing business in Indonesia.

![]() Economic Management

Economic Management

Indonesia has a capable central bank that has earned high marks from investors for its transparent communications and mindful management of the rupiah. The selection process for Bank Indonesia governors, who are appointed by the President with the approval of the House of Representatives, is similar to that of the US Federal Reserve. Bank Indonesia has steadily accumulated US dollar reserves, which have increased from USD24 billion in 1999 to USD120 billion today.

The Final Word

Indonesia compares favorably to its EM peers on several key ESG factors, namely central bank capacity, demographics, and energy access and management. We believe its advantages in these areas will allow it to better weather an economic downturn. The country has also made noteworthy progress on reducing income inequality and improving law enforcement. Combining these factors with our positive macroeconomic view and attractive valuations, our outlook on Indonesia sovereign bonds is constructive. However, the country continues to face significant and persistent challenges in a number of ESG areas, including corruption, GHG emissions, gender imbalances and external food dependency. We will continue to monitor developments across these areas and engage with government officials, multilateral banks and non-governmental organizations as appropriate.

- Jakarta Post, OECD, Transparency International, United Nations World Population Prospects, U.S. Energy Information Administration, World Bank, World Health Organization, World Resources Institute

- https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=73&t=11

- https://www.wri.org/blog/2018/08/indonesias-deforestation-dropped-60-percent-2017-theres-more-do

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD?locations=ID-Z4-4E GDP measured in constant 2010 USD

- https://www.indonesia-investments.com/news/news-columns/poverty-in-indonesia-fell-to-the-lowest-level-ever-in-march-2018/item8899?

- https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2018