Why All Defined-Benefit Plans are Short-Term Investors

Executive Summary

- Because of its need to make regular benefit payments, a DB pension plan simply cannot afford to behave like a long-term investor. It must be cognizant of short-term risks.

- Monte Carlo experiments we ran found a better than 50% chance of asset exhaustion (insolvency) for even an adequately-funded plan whenever asset returns varied randomly with some level of volatility.

- Fixed-income portfolios can reduce the risks of insolvency because they can be structured to match the maturity profile of the plan’s liabilities and because their random variations display more mean-reversion than do other asset types.

- All these results are just as relevant for public plans as for corporate and multi-employer plans. That is, our simulations were based on asset exhaustion, not of tracking a particular liability valuation (based on a particular accounting regime).

Section 1: Introduction

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Section 2: Path Matters! Timing Matters!

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Three Different Routes to Equity Returns (1944-2013 Experience)

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

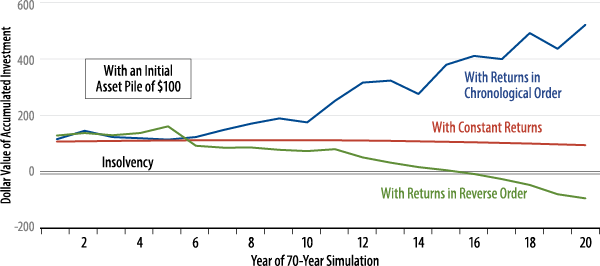

When DB Benefits are Paid Annually, the Same Average Asset Returns Result in Vastly Different Paths for Plan Assets

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Section 3: DB Plans Face Risk of Ruin With Virtually Any Level of Random Risk

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Probability of Bankruptcy Within 60 Years Depending on Initial Funding and Asset Return Volatility

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Section 4: Why Properly-Constructed Fixed-Income Allocations Substantially Reduce Risk of Ruin

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Section 5: Why Don’t Plan Bankruptcies Occur More Often?

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Section 6: Conclusions

At a pension plan conference not long ago, a plan manager asked, “Why can’t I just forget about de-risking and behave like a long-run investor: maximizing expected total return?” The simple and short answer is that because a defined-benefit (DB) plan makes regular benefit payments, it simply can’t afford to focus only on long-run returns. There is always substantial risk that a run of only modestly bad luck—combined with regular benefit payments—could so deplete assets that the plan could not recover even when and as asset returns rebounded to long-run averages.

The allure of the long-term investor arises from investment assumptions that are crucially different from those facing a DB plan. Decades ago, when Harry Markowitz and Paul Samuelson debated whether a “long-term investor” should care about risk or only return, they both considered an investor who could put funds away and let them accrue untouched until some terminal date. Because 100% losses in any specific period were assumed away, the investment pile never went to zero. So it would ultimately fully rebound once average asset returns had returned to their expected levels.

Once intervening—and regular—cash payouts are allowed for, everything changes. Cash payouts can exhaust assets in finite time when asset returns are only slightly negative or even positive but below-average, in which case assets remain depleted even when asset returns have averaged out to long-run norms. So, even long-run-minded investors can find themselves dead in the short-run (apologies to Keynes).

Furthermore, the risks of exhausting assets under a risky asset allocation are substantial. In the following sections, we’ll show that when asset returns randomly fluctuate alongside regular payouts, the chances of premature asset exhaustion look to be better than 50%, even with adequate initial funding. When initial funding is less than adequate, such insolvency is almost inevitable.

Every real-world DB plan faces the certainty of having to draw on invested assets well in advance of its “terminal date.” It simply can’t afford to act as a long-run investor. It must manage short-term risks. There are two steps a DB plan can follow to reduce the risk of asset exhaustion: it can tailor the risk aspects of its plan assets to match those of its liabilities and/or it can fund the plan in excess of what would be considered adequate.

With respect to risk matching, the plan will have some terminal date when final payouts are made. As time passes, that terminal date draws nearer, and its liabilities mature. Asset types such as equities, alternatives, and real estate do not mature, but proceed indefinitely, whereas fixed-income assets do mature. Thus, fixed-income portfolios can be structured to match the maturity structure of a plan’s liabilities in a way that other asset types cannot, thereby reducing the risks of asset exhaustion for the plan. Furthermore, fixed-income returns can be viewed as non-random—mean-reverting—and this also makes the chances of asset exhaustion less relevant for them.

As for more-than-adequate funding, this is an option regardless of the level of risk in the asset allocation, but it contravenes the cost-minimization motive that drives risky DB asset allocations in the first place. Also, the overfunding should be achieved early. If the plan waits until assets are nearly exhausted, even substantial subsequent contributions may not be sufficient. (Remember that asset exhaustion occurs not necessarily because of negative asset returns, but because of below-average returns alongside continuing cash payouts.) But here again, substantial overfunding runs counter to the desire to reduce pension costs.

Notice that these findings are just as relevant for a public plan as for a corporate plan. We deal here with avoiding asset exhaustion, not necessarily with minimizing funded status volatility. The real benefit of fixed-income assets to a DB plan is that they maximize the chances of plan solvency, an issue that is irrespective of accounting regimes. (Zero assets are zero assets regardless of what the liability valuation is accounted to be.)The fact that fixed-income assets do minimize funded-status volatility under a particular accounting regime is an indication of how well that accounting regime reflects the economics underlying the plan’s solvency. The particular accounting regime a plan faces is incidental to it. Maintaining solvency is a palpable reality.

Endnotes

- Exhibit 2 stops at year 20 in order to preserve some resolution in the chart. For the simulation through year 70, net assets under the blue line hit $45,000, from an initial level of $100. On the green line, they decline to -$58,000, while on the red line, they decline to exactly zero. With a scale wide enough to handle these extremes, the descents to zero assets at year 15 on the green line or at year 70 on the red line are not visible.

- Return/risk ratios were based on market results across a variety of assets over 1960–2013, using annual holding period returns.

- By way of comparison, long bonds and stocks exhibited annual return volatilities of 9% and 19% per year, respectively, over 1960–2013. Note also that when insolvency after 40 years is plotted, the probability is above 50% at volatility levels above 5%. So, the insolvency probabilities shown are not merely a reflection of assets being exhausted just prior to the 70-year terminal date.

- While corporate plans use high-grade bond yields to discount their cash flows to a present value, public plans use their expected return on assets. So, for a corporate plan, its liability valuation is independent of its asset allocation. Also, since its liability valuation is dependent on bond yields, bonds provide a good hedge of those liability accounting valuations. For a public plan, different asset allocations result in different expected returns on assets and so different liability valuations. Hedging liability accounting valuations thus becomes impossible. Still, as stated in the text, the economic features of the two types of plans are essentially identical, the only difference being that many public plan benefit flows are inflation-indexed, whereas most corporate plan benefit streams are not.

- With a 1989-2013 historical compound average return on equities of 10.26% and a 1989–2013 average return on liabilities of 9.38%, as per our simulated AA yields curves over 1988–2013, 100% initial funding as calculated in the text would correspond to an initial funded status of 93% as per FASB rules. So, even a 93% funded plan invested solely in equities would be likely to eventually become insolvent if that allocation were maintained. A 100% funded status as per FASB would correspond to 108% funding as calculated in the text and would result in about a 46% chance of eventual insolvency. The 120% initial funding mentioned in the text corresponds to a FASB funded status of 111%. These conversions to FASB funded status from the “initial funding” levels described in the text are dependent on specified “alphas” for equity returns over projected returns on FASB-generated liability valuations. As the latter are subjective and not directly historically observable, we don’t explicitly discuss these conversions in the text.