KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The 2019 rate cuts demonstrate that inflation now plays a much larger role in the Fed’s monetary policy decisions than it has in the past.

- The change in the Fed’s inflation outlook, in our view, was the primary motivator for the Fed to cut rates in 2019.

- It remains to be seen whether the Fed cuts are enough to sustainably boost inflation, however, and for the moment we doubt that they are.

- Our outlook for inflation to remain below 2%, together with the very high bar set by Chair Powell, suggests that the Fed is unlikely to raise rates in 2020.

- If the Fed is truly committed to boosting inflation, further rate cuts cannot be entirely ruled out for 2020.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) surprised almost everyone in 2019. It cut rates three successive times—July, September and October—in an environment of reasonably stable US economic growth, a falling unemployment rate and steady to rising risk markets.

The Fed’s willingness to cut rates in such an environment represented a distinct break from the previous two decades of monetary policy, in which the Fed primarily took its cues from either the labor market or the stock market. Investors who were slow to update their model of Fed behavior—and who, as a consequence, were expecting the Fed to tighten or at best remain on hold in the face of rising stocks and a lower unemployment rate—found themselves a step behind in 2019. Fortunately, Western Asset was not among that group.

Over the course of 2019 we argued that there was an ongoing shift in the Fed’s attitude toward inflation, which would likely lead it to easier policy at some point. While the Western Asset view was controversial at the beginning of the year, the contours of the Fed’s shift have subsequently become clearer and clearer. In particular, its rate cuts have served as a tangible validation of our view. If there was an error in our analysis, it was that we didn’t take it far enough. We harbored some lingering doubts about whether the Fed had truly changed its stripes, and therefore we were a bit too timid in forecasting the amount of rate cuts. Yet the rate cuts came and then kept coming, even as growth and markets held steady.

The Fed’s rate cuts last year have implications for the 2020 outlook. First, the 2019 rate cuts demonstrate that inflation now plays a much larger role in the Fed’s monetary policy decisions than it has in the past. Second, the focus on low inflation has moved the Fed toward a “make-up” strategy, whereby the Fed would seek to offset periods of below 2% inflation with periods of above 2% inflation. Any such “make-up” strategy implies the bar for future hikes has been set quite high. Finally, in 2019 the Fed showed it is willing to back its inflation objective with policy actions. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has insisted that willingness remains in place. This means a further easing of policy cannot be ruled out, and would become increasingly likely if inflation failed to rise in line with Fed expectations.

Inflation in Focus

Our view is that the rate cuts of 2019 were first and foremost about inflation. Other explanations were offered at the time and have continued to be promoted since, including “insurance cuts” and as a response to a global economic slowdown. These other explanations are unconvincing, in our view, as they neither fit the fact pattern nor do they answer the question of what compelled the Fed to act in excess of almost everybody’s expectations.

The analogy between 2019 and the “insurance cuts” of 1998 seems particularly unhelpful. It’s true there are similarities. For example, the Fed cut the same amount in both years (0.75%) and there were fears surrounding an emerging market economy in both years (Russia in 1998, China in 2019). But these similarities are overshadowed by the differences. One significant difference is that in 1998 the Fed was responding to what was, at the time, a widespread and growing concern about financial markets in general, and the vulnerabilities of levered investors in particular. By the time the Fed first cut rates in September 1998, the S&P 500 had declined 10% from its peak and huge losses had forced Long Term Capital Management to shut down. Needless to say no equivalent financial market stress was seen in 2019, as in fact the S&P was higher at the time of the Fed’s July cut than it was at the time of the Fed’s last hike.

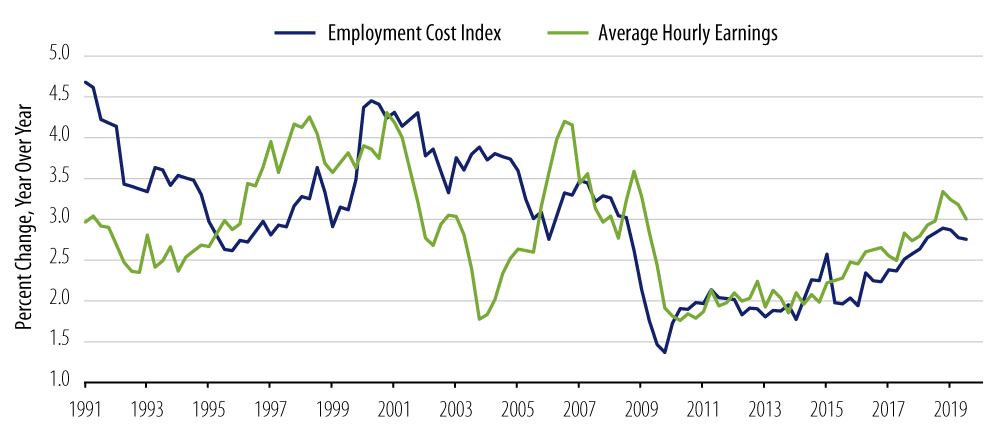

Rather than “insurance cuts,” the most obvious explanation for the Fed’s rate cuts in 2019 was a focus on inflation, and in particular a renewed concern about below-target inflation. In contrast to 2018, when the inflation outlook was favorable and the Fed was hiking accordingly, the inflation data in 2019 was disappointing pretty much across the board. Of particular note was the plateauing and slight deceleration of wage inflation (Exhibit 1). While wage inflation is not explicitly included in the Fed’s mandate, it carries elevated significance because of its salience for workers and its more immediate connection to the full employment part of the Fed’s mandate. Also of note was the decline in inflation expectations, for example, as measured by TIPS breakeven inflation, which ended the year suggesting that future inflation would remain decidedly below the Fed’s 2% objective (Exhibit 2). Finally, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, core personal consumption expenditures (PCE), moved lower in 2019 due to a combination of idiosyncratic events as well as ongoing softness in services inflation. Taken together, the stall in wage inflation, the notable decline in inflation expectations and the below-mandate prints for core PCE suggest a much more troubled outlook for future inflation than the Fed maintained previously. This change in inflation outlook, in our view, was the primary motivator for the Fed to cut rates in 2019.

Obviously the link between inflation and the 2019 rate cuts is clearer with the benefit of hindsight. Over the course of the year, Fed officials themselves gave a series of muddled explanations for their actions, often finding it convenient to cite multiple rationales at the same time. However, by the final rate cut in October the other reasons had declined in importance and all that was really left was a heightened concern about low inflation. At that meeting the Fed admitted that the uncertainty about global events had receded and that US growth continued to be rather sturdy, yet the Fed cut rates anyway. In his last press conference of 2019, Chair Powell returned again and again to the subject of low inflation, highlighting in a variety of contexts how low inflation had influenced the decision to cut rates. Here are a few examples of Powell’s emphasis on inflation from that press conference¹:

“As you can see, inflation is barely moving up, notwithstanding that unemployment is at 50-year lows and expected to remain there … In fact, we need some upward pressure on inflation to get back to 2 percent.”

“We believe that policy is somewhat accommodative, and we think that that’s the appropriate place for policy to be in order to drive up inflation.”

“That underscores, I think, the challenge of getting inflation to move up. The Committee has wanted inflation to be at 2 percent, squarely at 2 percent, for—ever since I arrived in 2012. And it hasn’t happened, and it’s just—it’s because there are disinflationary forces around the world, and they’ve been stronger than, I think, people understood them to be.”

Powell’s message was unmistakable: low inflation was the key to understanding the Fed’s actions in 2019. In our view, it’s likely to also be the key going forward as well.

High Bar for Future Rate Hikes

“So I think we would need to see a really significant move up in inflation that’s persistent before we would consider raising rates to address inflation concerns.” – Chair Powell, October 2019

Not only did the concern about low inflation play a significant role in motivating cuts in 2019, but it also appears to have shaped how the Fed intends to conduct policy going forward. In particular, a number of Fed speakers have mentioned the desirability of a “make-up” strategy with regard to inflation, whereby periods of inflation below 2% would be offset by periods of inflation above 2%. The details of such a strategy are still being debated, and it could take a few months for the specifics to be announced as official Fed policy.

It would be a mistake, however, to wait for the official announcement to incorporate this into the outlook. Indeed, based on his recent comments, it appears Chair Powell has already embraced a “make-up” strategy. In each of the last two press conferences Chair Powell has said that in order to raise rates he would need to see “a really significant move up in inflation that’s persistent.” Given the starting point of the Fed’s preferred inflation measure (core PCE at 1.6%), it seems fair to conclude that a “really significant move up” would take inflation above 2%. It also seems fair to interpret Powell’s inclusion of “persistent” in the criteria as a response to the extended period of below-target inflation. Powell’s guidance, which he has now repeated twice in response to direct questions, is therefore essentially to adopt a make-up strategy.

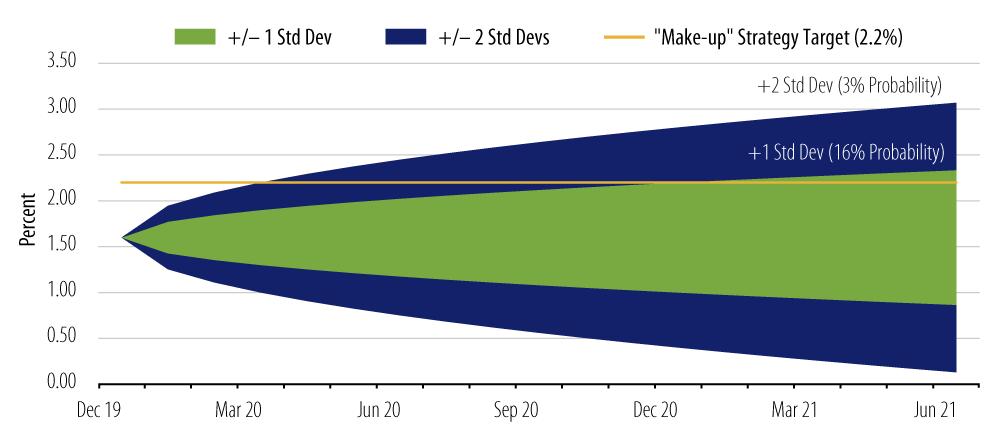

The important conclusion is that Powell’s make-up strategy sets the bar for future rate hikes exceptionally high. To put this into perspective, consider the following back-of-the-envelope calculation. Based on Powell’s comments, it seems reasonable to assume that core PCE would need to be 2.2% or higher for at least six months to justify a rate increase. (These assumptions are made to be consistent with Powell’s “really significant” and “persistent” criteria. But the point here is a general one and the conclusion would likely hold under whatever final formulation the Fed arrives at for its make-up strategy.) Further, note that the annual volatility of core PCE over the last 20 years has been 0.6%. Based on these assumptions and the historical volatility of inflation, there is a less than 7.5% chance that Powell’s criteria would be satisfied by the end of 2020 (Exhibit 3).

Three caveats are warranted for this rough calculation. First, Powell was careful to qualify his criteria by saying that it has not yet been made into official forward guidance. Official codification could happen when the Fed finishes its ongoing strategy review—and in our view it likely will happen when the review is finalized—but until then there is some risk of back-tracking. Second, the Fed could theoretically be motivated to increase rates for some reason other than inflation, potentially to address financial stability concerns. That said, the risk here seems rather small at the moment, especially as there are other tools the Fed could deploy if financial stability concerns were to mount much further (for example, the counter-cyclical capital buffer). Finally, this analysis does not incorporate an inflation forecast, but instead simply reflects historical volatility of inflation. Incorporating an inflation forecast would obviously affect these probabilities. This is the topic we address in the next section.

What If Inflation Doesn’t Rise?

Our back-of-the-envelope calculation was based on only the historical volatility of inflation. Accordingly, it did not incorporate a forecast of inflation. Our view at Western Asset is that inflation is unlikely to rise above 2% in the near future. As we discussed in a paper last year, Falling Inflation Could Move the Fed, neither the bottom-up nor the topdown analysis of inflation indicates a strong case for an acceleration. The Fed’s actions since that paper was written make the top-down case for an inflation acceleration slightly stronger at the margin. It remains to be seen whether the Fed cuts are enough, however, and for the moment we doubt that they are. The global disinflationary headwinds remain firmly in place, and the bottom-up analysis doesn’t suggest much has changed.

Our outlook for inflation to remain below 2%, together with the very high bar set by Chair Powell, suggests that the Fed is unlikely to raise rates in 2020. In particular, given our low inflation outlook, the probability of a rate increase due to inflation appears to be even less than the 7.5% calculated in the previous section. What makes this conclusion all the more notable is that there is a healthy margin of safety in our analysis. Even if inflation were to move up somewhat, and even if it were to exceed our expectations and reach 2% next year, that would still be insufficient to generate a Fed response.

A trickier question is whether another year of below 2% inflation could motivate the Fed to continue cutting rates. In other words, could 2020 see a repeat of 2019 in terms of Fed cuts? There are reasons to doubt the Fed’s willingness to continue cutting, including the US election cycle and a much-discussed split of views within the Fed. In addition, the outlook for growth and risk markets has turned up recently, due in part to reduced political and trade risks. It’s hard for the Fed to cut into a brightening growth outlook.

Yet, many of those same claims could have been made at various points in 2019, and the Fed cut rates anyway. The experience of 2019 showed that the Fed is indeed capable of acting to support inflation, and is also capable of overcoming the common objections to doing so. Chair Powell has insisted that the Fed remains committed to boosting inflation. He has further said that the Fed’s commitment extends beyond words and will result in actions when needed. Therefore, it seems unadvisable to fully rule out further rate cuts. While not quite the base case, if the Fed is truly committed to boosting inflation, it may turn out that the Fed is compelled to cut again sometime in 2020.

Conclusion

As we reflect on what changed in 2019 we are struck first by the number of things that did not change. The economic recovery remains ongoing, although unspectacular in magnitude. The policy backdrop remains challenging, although arguably not any more so than at the beginning of the year, especially with regard to trade policy, where there has been some recent relief. And inflation remains very subdued both in the US and around the world.

What does appear to have changed, however, is the Fed’s willingness to act to support inflation. The Fed’s three cuts in 2019 surprised anybody who expected monetary policy to be determined primarily by the unemployment rate or by risk markets. Such a view may have been understandable—after all, it had accurately described the Fed’s behavior for the prior two decades—but it was worse than inaccurate in 2019.

In contrast to many investors, Western Asset was positioned on the correct side of the Fed outlook in 2019 because we recognized early on that the Fed had adopted a new focus on inflation. Going forward, the Fed’s new focus on inflation implies a high bar, and therefore low probability, for future hikes. Chair Powell made this clear when he said his criteria for rate hikes is “a really significant move up” in inflation that is “persistent.” Finally, a new focus on inflation means that further cuts cannot entirely be ruled out, especially if inflation continues to challenge the Fed by remaining below 2%.

- Federal Reserve FOMC Press Conference 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20191211.pdf